ICT as a Social Support Mechanism for Family Caregivers

of People with Chronic Illness:

a Case Study

Las TIC como un mecanismo de apoyo social para cuidadores

de familia de pacientes con enfermedad crónica:

un estudio de caso

As TIC como um mecanismo de apoio social para cuidadores

de família de pacientes com doença crônica:

um estudo de caso

Recibido: 26 de junio de 2012

Aceptado: 11 de marzo de 2013

Lorena Chaparro-Díaz

BSN, DNS. Assistant Professor, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

olchaparrod@unal.edu.co

|

ABSTRACT Introduction: Social support encouraged by nurses and as a strategy for family caregivers (FCs) is a phenomenon that, although old, is currently challenged to promote care through online social networks. Objective: To describe and analyze the use of information and communication technology (ICT) as a social support mechanism for FCs of individuals with chronic illnesses. Design: The method was a descriptive exploratory study with a qualitative approach undertaken in Bogota in 2010. The case study included 20 FCs of individuals with chronic illnesses who used a blog. Based on Rodger's theoretical model the ICT strategy "Diffusion of innovations" was created in three phases: 1) Blog design allowing interactions through chat, forum, and email consultation. 2) Implementing the strategy for 4 months with 16 hours a day caregiver support service; the information was obtained through field diaries and a final interview. 3) Analysis of the information to describe how caregivers perceived the social support obtained through blog use. Results: The results describe the way in which they perceived their technological abilities and their ability to use the blog. The main categories found were care, interaction, experience, and technology. Discussion: Results were compared with those from social support reports addressing e-learning for health and theoretical perspectives on online social support. KEY WORDS Nursing, caregivers, medical informatics, chronic disease, health. (Source: DeCs, BIREME). |

RESUMEN Introducción: el apoyo social respaldado por las enfermeras como una estrategia para los cuidadores de familia es un fenómeno que aunque viene de tiempo atrás, en la actualidad tiene el reto de promover el cuidado a través de las redes sociales en línea. Objetivo: describir y analizar el uso de las tecnologías de información y comunicación (TIC) como un mecanismo de apoyo social para los cuidadores familiares de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas. Diseño: el método que se utilizó fue un estudio exploratorio descriptivo con un enfoque cualitativo que se llevó a cabo en Bogotá en el año 2010. El estudio de caso incluyó a veinte cuidadores de familia de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas y que usaron un blog. Con base en el modelo teórico de Rodger, se creó la estrategia de TIC "Difusión de innovaciones" en tres fases: 1) Diseño del blog de manera que permita las interacciones a través del chat, foros y consulta por correo electrónico. 2) Implementación de la estrategia durante cuatro meses con un servicio de apoyo del cuidador de dieciséis horas al día. La información se obtuvo por medio de diarios de campo y una entrevista final. 3) Análisis de la información para describir de qué modo perciben los cuidadores el apoyo social que se obtiene a través del uso del blog. Resultados: los resultados describen la forma en la que ellos perciben sus habilidades tecnológicas y su capacidad para usar el blog. Las principales categorías que se encontraron fueron cuidado, interacción, experiencia y tecnología. Discusión: los resultados se compararon con los de los informes de apoyo social que abordan el aprendizaje virtual para la salud y perspectivas teóricas sobre el apoyo social en línea. PALABRAS CLAVE Enfermería, cuidadores, informática médica, enfermedad crónica, salud. (Fuente: DeCs, BIREME). |

RESUMO Introdução: o apoio social respaldado pelas enfermeiras como uma estratégia para os cuidadores de família é um fenômeno que, embora venha de tempo atrás, na atualidade tem o desafio de promover o cuidado por meio das redes sociais on-line. Objetivo: descrever e analisar o uso das tecnologias de informação e comunicação (TIC) como um mecanismo de apoio social para os cuidadores familiares de pacientes com doenças crônicas. Desenho: o método que se utilizou foi um estudo exploratório descritivo com um enfoque qualitativo que se realizou em Bogotá em 2010. O estudo de caso incluiu a vinte cuidadores de família de pacientes com doenças crônicas e que usaram um blog. Com base no modelo teórico de Rodger, criou-se a estratégia de TIC "Difusão de inovações" em três fases: 1) Desenho do blog de maneira que permita as interações por meio de chat, fóruns e consulta por correio eletrônico. 2) Implementação da estratégia durante quatro meses com um serviço de apoio do cuidador de dezesseis horas por dia (a informação se obteve por meio de diários de campo e uma entrevista final). 3) Análise da informação para descrever de que modo os cuidadores percebem o apoio social que se obtém pelo uso do blog. Resultados: os resultados descrevem a forma na qual eles percebem suas habilidades tecnológicas e sua capacidade para usar o blog. As principais categorias que se encontraram foram: cuidado, interação, experiência e tecnologia. Discussão: os resultados se compararam com os dos relatórios de apoio social que abordam a aprendizagem virtual para a saúde e perspectivas teóricas sobre o apoio social on-line. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Enfermagem, cuidadores, informática médica, doença crônica, saúde. (Fonte: DeCs, BIREME). |

Introduction

Latin America has been attempting to find the most useful strategies to address and manage the progressive increase in chronic illnesses (Pan American Health Organization, 2007). Chronic illnesses entail major social and economic costs and significantly reduce productive years. The required long-term care, frequent hospitalizations and risks resulting from ignoring the condition, alter interpersonal relationships and generate isolation and a great sense of discomfort with health and life in general (Kane et al., 2005 and Barrera, Pinto, & Sanchez, 2010).

The significance of chronic illness as a social phenomenon (Newman, 1994) and the philosophy of how to approach chronic illness can be viewed from three perspectives: classification, experience, and perceptions (Barrera, et al., 2010). Coping with a chronic illness pertains not only to the patient but to the family caregiver (FC) who is alongside him/her and becomes an important agent for the healthcare system; they undertake the responsibility of caring for their loved one and participating in decision making even though they have no social or legal recognition. "He performs or supervises the activities of daily life to compensate the existing dysfunctions of the recipient of care." (Barrera, Galvis, Pinto, Moreno, Pinzon, Romero, et al., 2006).

We must recognize that providing care creates special needs that continue over time (Pinto, & Sanchez, 2000). When caregivers have social support to ease their workload, they can usually strengthen their skills, thus contributing to their loved ones' quality of life as they care for them.

Social support (SS) has been widely described, and its relevance in looking after individuals with chronic illness has been recognized (Lindsey, & Yates, 2004, Tilden, 1985; Hupcey, 1998 & Finfgeld-Connett, 2005). SS involves the sharing of information and provides feelings of being cared for, loved, esteemed, and valued as a member of a network (Cobb, 1976 Quoted by Lindsey, et al. 2003). The concept includes four functional dimensions: emotional, instrumental, informational, and validation (House, 1981). It can have a positive impact mostly on health and welfare (Hinson, Bowsher, Maloney, & Lillis, 1997), and it differs from merely being looked after (Finfgeld-Connett, 2007). It is explicit in the context of chronic illness (Vrabec, 1997), and there are different categories in how this support performs (Hilbert, 1990).

Humans have an essential need to connect with others, and connections are enhanced where there is timely and effective communication. This need is perhaps why one of the Millennium Objectives considers enhancing the use of technological devices through "building a global partnership for development" (United Nations Organization, 2010) to promote a global society. With technological advances, social networks have had great economic, social, and scientific impacts that can support healthcare. In this sense, information and communication technologies (ICTs) have three possible developmental fronts that must be studied and promoted: the institution, the system itself, and users and professional agents (Peña, 2004; Nadal, 2007; Ramos, 2007; Torrente, Escarrabill, & Martí, 2010).

Healthcare users today are not passive individuals, and cutting-edge technologies are a means of guiding them to a healthier and happier lifestyle. Thanks to technology, patients and their families encourage research and seek to improve treatments and quality of life (Armayones and Sanchez, 2011).

The e-patient concept was introduced by Fergusson et al. (2004) as a "proactive patient with good knowledge of technologies, involved in maintaining their health and interested in contributing not only to treatment and research on specific health conditions but also to improve the health care system". This concept extends to health service users, including patients with chronic illnesses and their FC (Schachinger, 2010).

The legislative perspective worldwide has been changing to accommodate ICT in healthcare (Vélez. 2010). In Colombia, more changes have happened at the institutional level than in the system itself or among professionals. Telemedicine is the main focus of legal standards (Res. 1448 of 2006 Ministry of Social Protection), especially in areas of the country that are difficult to access (Law 1122 of 2007 Ministry of Social Protection) and for the specific goals included in the National Public Health Plan 2007-2010 (ICT Plan Colombia).

Information technology and communication (ICT), has been described as a tool with which to provide social support; it is defined as "strategies to create support networks and provide a support system with better monitoring, integrated through connections media and online support, facilitating permanent interactions among people with chronic illness, their caregivers and the health systems" (Cardenas et al, 2010).

ICT enables collecting, systematizing and disseminating information in order to promote learning and skills in people with chronic illness and their caregivers (Struk et al, 2009). This forwards how they learn to cope with the situation regarding oncoming behavioral changes and an altered lifestyle (Barrera et al, 2007) thus decreasing accessibility barriers and high service fees. (Barrera et al, 2008, Weiner et al, 2005).

Although the use ICTs appears to have increased, access to specialty-based information provided through institutional websites, the use of call centers, the use of e-mail for communicating laboratory results and diagnostic images, access to a treating physician's cellphone, health chat services, and phone-made appointments have not been well described in Colombia. Healthcare and its relationship with the use of ICT as a key element in supporting the care of people with chronic illnesses have not been systematically addressed.

Materials and Methods

An exploratory descriptive study with a qualitative approach and a case study design described and analyzed the use of ICT (using a blog) as a social support mechanism for FC of people with chronic illnesses. It was necessary to start with a conceptual approach that would allow observing the phenomenon of a social support network as an essential element of care to meet the challenge of having a relative with a chronic illness (LaCoursiere, 2001, Brennan, Moore, & Smyth, 1991). Rogers' "Diffusion of Innovations" theory (1983) reinforced how the study developed in the understanding that support should be comprehensive, innovative, affordable, compatible, and beneficial. It should also respond to the characteristics of the caregiver in the situation that he or she is facing, including the workload, degree of isolation, and decision-making process, and the response to the caregiver's interaction with technology. Therefore, the study proceeded in three stages: An initial stage, in which we designed an online social media strategy for FCs of individuals with a chronic illness that eases the interaction between participants through chat, forums, and video forums. Access can be free or restricted depending on the group's decision; it was structured as a blog named "Paratucuidadoenlinea".

The second stage is the intermediate stage, in which we implemented a strategy to link the participants into the blog through training in tool use and developing a tracking system to identify indicators of ICT use, access, and ownership. The stage lasted for four months and included 16-hour daily availability for consultation, advice to the FC via chat, and using a visit counter to monitor forum participation. The informants were selected based on those involved in strategies used for social support technologies. Information was obtained through observations registered in the field diary of each of the cases and open-ended interviews conducted after this stage of the study. Interviews were conducted by the same blog and chat, as well as through phone calls. All of the participants' activities whether via chat and/or the forum were transcribed verbatim in the field diaries.

Last of all, is the final stage, during which information was analyzed. This process began with organizing the field diary of each case, the transcripts of the studies via chat and/or forum, and interviews. Elements were then extracted, and codes and categories were built regarding the FC's experiences and perceptions while using the tools. Finally, the codes and categories were grouped into dimensions and due to the large number of categories the qualitative research program AtlasTi was used to consolidate the information, (National University of Colombia. AtlasTi. Version 6.0.12).

Credibility, trustworthiness, transferability, dependability and confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) guided this process. For example, carefully rereading the interview and field notes in order to compare cases assured credibility. Interpretations were shared with other researchers of this study. Thus, holding discussions with the research group checked codes and categories.

Ethical issues such as informed consent, voluntary participation, handling confidential information, and the approval of relevant authorities in support of the Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing at the National University of Colombia were considered in this study. Environmental impact was assessed and considered positive because the strategy implemented reduces the use of both paper and ground transportation.

Results

A blog under the name "Paratucuidadoenlinea was structured using questions to characterize the information needs of the caregivers and guide their role. Twenty FCs of people with chronic illness (CI) were given access to the blog. 19 were females between 30 and 63 years old, while the remaining one was a 70-year-old male. Their education levels varied from being unable to complete elementary school (1), unable to finish high school (3), high school graduates (3), technical apprentices (2), college dropouts (2), and college graduates (8). Regarding marital status, one was separated, three were single, two lived in civil union, four were widows, and nine were married (including the male). In regards to occupation, one was a student, two were employed, four were retired, six worked free-lance, and seven worked from home. Caregivers were of varied kinships including daughter in-law (1), granddaughter (1), friend (2), sister (2), niece (2), husband/wife (3), and daughter (8). From this characterization, Rogers' theory indicates that intermediate ages are more easily motivated towards using ICT, which is contrary to what one might think that is true of young adults. Although not exclusive, the educational background is a beneficial influential factor.

In a previous knowledge survey, skills in computer use were self-rated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very knowledgeable). Three FCs rated themselves as very low (0 to 1), seven as low (2 to 4), seven as fair (5 to 7), and three as good (8 to 10). For Internet use, 16 FCs stated that they occasionally used the Internet and 4 did not. Likewise, 4 FCs said they had no computer or Internet at home, 3 had a computer at home but no Internet, and 13 had a computer and Internet. Three people used hourly Internet rooms, and all had access to rooms provided by the project on campus at Colombia's National University if they so required. Self-rating between low and very low reflects that access may be limited in a stage prior to these types of interventions; however, that does not minimize its innovative nature at all. On the contrary, when they recognize the benefits they prefer them to some of the aspects involved in sessions held on site.

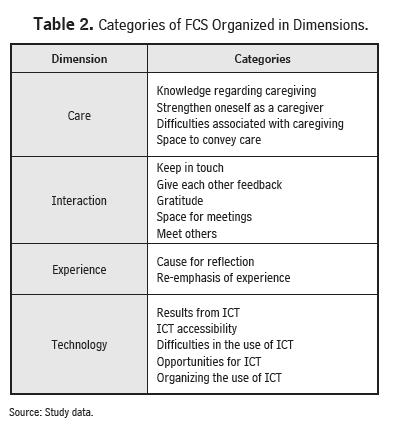

Training was organized at the most convenient times for the FC, either in person or with the use of General Internet and Blog Management guidebooks. A 6 to 28 hour range was required with an average of 13.4 hours, and the general guidebook provision was required for 12 of the 20 FCs. One caregiver received additional training by email. Five FCs stated that they always used the Blog Management guidebook, 5 used it infrequently, and 10 almost always used it (Table 1. FCs of people with a chronic illness who participated in the study).

The FCs showed interest in getting involved with the blog, and although some of them had difficulties accessing it, the problem was overcome with support and training. The participants' names were used as their identification on the blog. One of the activities was publishing videos of interest, which generally evoked feelings, memories, or good wishes for others. It was common to form couples to use the training or provide feedback because having a partner who had greater knowledge in the use of the blog could be more effective than the use of the supporting material. Finally, not all of the participants became permanent users. However, the greatest benefits identified included the counselor's perception in each case and the positive assessment of the learning achieved as well as having space on campus (institutional facility) to give FCs the opportunity to enter the world of ICT at least once a week. The participation and interaction on proposed topics motivated the FCs to request more information or information on new issues and to express feeling confident about the knowledge acquired. Also, they were encouraged to give recommendations that were monitored by the nurse (counselor). The validation of the information received and requested was paramount for the FCs because they were certain that the person responding to their requests was a highly skilled nurse with institutional support and special communication features to understand complex issues. Providing step-by-step guidelines and instructions, drawing attention to inappropriate practices, and providing timely, relevant, and easy to perform solutions were necessary to reinforce this knowledge. The blog offered themes such as first aid and skin care. Innovation from Rogers' perspective is consistent with classifying ICT users in: a) innovative caregivers: those who cope adequately with having to face, ask for or go to the directory to solve concerns, b) those who adopt ICT in an early stage, who are caregivers claiming that they occasionally use additional information on the use of ICT or a counterpart to guide them; c) those who start and use it regularly, but only when there are specific concerns or under a motivating factor such as a videos or topics of general interest, d) those starting later, who must first understand the guidelines to make them operational and have constant validation on the use of ICT and e) those who definitely show mistrust but who are also occasional ICT users; these include those who used the rooms available on campus. Case analysis was based on the field diaries (from telephone conversations and reflections of the counselor), information recorded on the blog, and open questions asked at the end of blog participation. Based on these sources, the information was organized in nouns and nominal codes that were grouped into categories after reaffirming their names. There were a total of 193 codes representing the core of participants' testimonies just as they were interpreted, without preconceptions, and based on the descriptions and the reflections of the investigator. Finally, the codes were grouped into four dimensions: Care, Interaction, Experience, and Technology (Table 2. FC categories organized into dimensions). Overall, these four dimensions define the use of a blog as a social support mechanism for the FCs of individuals with a chronic illness.

Care. This dimension refers to the ways in which the family caregiver takes from his or her innermost human essence the skills needed to face committing to a chronically ill loved one, what he or she should know about the disease, how to meet oncoming challenges, and the ability to establish interpersonal relationships that will forward human development; it also refers to understanding the difficulties that this experience brings to everyday life where social support becomes an opportunity.

FCs feel that this work involves being constantly updated, looking for different ways to find the necessary information about the disease, coming closer to what their loved one feels regarding their situation, occasionally identifying similarities between the patient's condition with his or her personal health status; they also feels it requires gaining knowledge regarding specialty care and the specific terminology required to discuss topics such as "pressure sores" or "take your blood pressure" even when, prior to their role as FC they were even unaware of how to spell them. Knowledge is closely related to self-improvement as a care-giver because the valuing the knowledge acquired reveals that appreciates receiving tangible input to support his or her work. This desire for improvement is evidenced through a two-way interaction between the caregiver and counselor and by the opportunity to assess the knowledge and experience of other FCs. In this regard, care is closely related to the dimension of interaction. It is only possible to improve as a caregiver when there is interaction with others and when the caregiver expresses the need and desire to implement what has been learned into expanding this knowledge into everyday life.

Interaction. The interaction dimension was observed starting from the process of training in the use of ICT. The FCs expressed interest in retaining the offer to receive training in accordance with each FC's needs. The FCs kept in contact with their peers and with the counselor with phrases of good wishes and by establishing meetings or commitments either virtually or in-person. Other forms of interaction involved establishing communication patterns, such as welcome greetings, invitations to follow the blog, integration, remembering special days, and greeting at the beginning and at the end of each session. The "desired link" is a key element of an online support group to be considered. Participants were already part of an in-person support group, and they established a stronger bond through the use of ICT. Interactions also involved feedback from others and self-reflection. Language, including phrases created or evoked by each individual, was an essential part of this dimension. In addition, essential parts of the interaction include expressions of satisfaction regarding the information learned, assessments as human beings, identifying possible solutions, and recognizing the network. How feelings were expressed was qualified by the gratitude and empathy between the counselor and the FC. Counselor interactions were evaluated according to their patience, time, dedication, and accessibility to the FC. In this dimension, the blog was perceived as a meeting place, comparable to in-person support, which helped to identify and exchange experiences, provide virtual entertainment, display preferences, and answer questions. Moreover, the FCs can receive training, develop skills, receive support; meet others, identify their strengths, be recognized as peers, and establish a shared body of work.

Experience. The experience dimension has two categories that reflect the intangible aspects of caregiving. Recorded phrases, whether evoked or created, reflect the caregiver's spirituality and his or her ideas on friendship, with which the caregiver gives meaning to his or her work. In addition, religious phrases are offered to protect the caregiver and the individual suffering from chronic illness. Interaction and knowledge about care are intertwined with the FC's experience, generating greater security and a greater ability to recognize that once knowledge is acquired, it should be shared. Experience provides security in anticipation of tougher times that are sure to come.

Technology. In this dimension, the categories reflect the outcome of the information provided: how to take risks and submit questions about the care of a family member, explore the network, give identity to their space (profile picture), identify the supporting material, and use ICT as the basis to determine appropriate solutions. In some cases, access did not require support from a counselor, and the FCs acknowledged having support from peers that had more knowledge. They appreciated different communication channels (telephone) and advantages, such as not having a precise timetable to participate.

Difficulties using the blog were associated with the fear of using technology. At first, FCs harbored the myth of "damaging the computer, but as they received training, they became less afraid, and their anxiety was reduced. However, other difficulties were evidenced, such as not using the guidelines provided at the appropriate times, identifying very similar visual images from the Internet across multiple platforms, not having their own computer, having to share a computer with other relatives or caregivers, and requiring special software for video applications. Opportunities were also recognized such as the learning of something unplanned. They were eager to inform other FCs about the existence of these tools, and they appreciated that the strategies were not only to read documents but also to play, interact, publish, receive feedback, lose their fear of technology, be motivated, develop typing skills, access, and connect. This led them to consider the need to organize ICT support, seek clarifications, acquire greater psychomotor skills, seek support from a younger relative, and continue training. At the same time, they required monitoring and support to learn the material, manage schedules and availability, and combine in-person and virtual sessions in order to participate. Evidently, the FCs performed strategies to appropriate ICT.

By contrasting the use of the blog section versus telephone follow-up, it became clear that the better-developed strategies were related to the use of the chat and forum, which focused on the interaction of the counselor with peers, encouraging ongoing reflection and recognizing the potential use of the tool.

Appropriation is classified as intermediate regarding reference topics because the FCs were allowed to suggest topics; new concerns arose from these suggestions and were related to care, interactions, and the use of ICT information for living as a FC. Virtual consultations and e-mail (the latter was almost null) had the lowest use. The FCs focused on expressing interest but lacked feedback on knowledge acquired. Finally, telephone follow-up participation was punctual and associated with questions about care, commitment to continuing the use of ICT, or requests for in-person meetings.

In sum, the analytical categories were grouped into the dimensions of care, interaction, experience, and technology, which summarize how the use of ICTs, in this case the blog "Paratucuidadoenlinea , developed as a social support mechanism for FCs.

Discussion

The discussion presents three perspectives on the current state of knowledge: social support, the use of ICT in healthcare, and theoretical perspectives on innovation and social online media. As for social support, and regarding Vrabec's proposal (1997), "Maintain contact is from the structural dimension, the category that supports the network or the relationship between peers; with regard to the functional dimension, emotional support is based on the "Space to deliver care , "Space for meetings , "Maintain contact", "Food for thought" and "Re-emphasis of experience" categories. For instrumental-information support, the categories are "Knowledge for caregiving" and "Difficulties associated with the caregiving . In validation, the support categories found were "Strengthen ourselves as caregivers and "Give each other feedback . Finally, the results in regard to satisfaction are "Results from ICT and "Gratitude . In this same dimension, the technology categories contribute towards understanding the concept in the context of using technology, as proposed by Williams, Barclay, & Schmied (2004). Social support depends on a group of caregivers, who know and wish to remain as such, and where emotional elements are prioritized in order to weave the threads of the network; each caregiver exposes that his/her experience and expertise is in the direct care and should be accompanied by a formal or more skilled caregiver. This indicates that social support interventions must have basic elements of social networks, in order to help reduce the burden, share with others and allow people to see that they are not alone and should be assessed mainly by a health care professional, thus integrating care within social support.

Concerning the use of ICT in health defined as a social media strategy, the blog "Paratucuidadoenlinea , allowed valuing FCs as individuals who despite their education level can still undertake a new learning process, as each of these FCs was able to acquire valuable new knowledge at the right time. FCs commonly require formal spaces in which to participate, and this was perceived as an opportunity to interact differently, to share resources simultaneously, and to express their thoughts.

Some care needs arose from the interaction between the FC and the counselor. In this regard, Pierce, Steiner, & Govoni (2002), in a care-related Internet tool (which is not strictly social support), also found the need to suggest websites and games that promote abilities and leisure activities, draw attention to the importance of going to a medical facility, provide information on the proper use of medications and their indications and side effects, and provide information systems and social support resources that can be consulted later. Kernisan, Sweat, & Knight (2010) synthesized information on healthcare practices, behaviors, and support and obtained similar results.

The dimension experience categories are related to the findings of Klemm & Wheeler (2005), who identified hope as a part of the learning experience. Klemm et al. (2005) found that emotional aspects fluctuated; on the contrary, in the present study, the expression of negative aspects of the experience were not as explicit, as noted by the difficulties category associated with caregiving.

Although this intervention was not essentially based on the telephone as a strategy for monitoring blog use, some telephone contacts were included. Kerr et al. (2006) found with an intervention of this kind that this strategy allows the FC to respond to difficulties in the use of ICT, such as not being able to attend the Internet lounge and visual confusion (such as differences between email, webpages, and software required to view resources). Another advantage of having telephone contact was the ability to respond to concerns about health services and provide more intimate emotional support.

One dimension that is directly related to technology is interaction, thus confirming that strong bonds between the FC, the counselor, the formal support group, and even the institution that provided the intervention are created and expressed through the constant gratitude shown in messages and thoughts. Sullivan (2008) found a link in caregivers for children with asthma in a category called "we are here to provide support when needed". Based on the findings, ICT -in health- can be defined as an opportunity to interact with peers in innovative and entertaining environments; it shows new needs that are not perceived in consultation or workshops (inadequate care practices), maintains ongoing analysis that encourages the caregivers and generates new links to recognize the other person from what he/she feels and expresses, not only from their physical appearance or compatibility in social relationships. Finally, regarding the theoretical prospects for online innovation and social support, great relationships exist to develop a strategy based on the results and the projections of Telenursing online. In the Theory of Diffusion of Innovations1 Rogers (1983) states that participants' characteristics are key factors that influence how innovation is adopted. This was a characterization study corresponding to the profile of FCs in the global and local context, including middle-aged women (35-65 years) with high educational levels. Therefore, a short and effective training period was expected, but the use of new tools required more time to respond to concerns arising in regard to their proper use. This means that educational level did not create differences within the FC group because in this regard, they were all at the same level. In general, the FCs were middle-aged and in an upper socioeconomic stratum. Most of them had technological resources at home. However, ignorance hindered them from using this technology, thus confirming that despite having the resources, their training and guidance regarding their proper use had been inadequate. The most persuasive aspect of the blog was how FCs perceived that the knowledge expressed caregivers and that the opportunity to interact and share their experiences will enrich their lives and provide security. The decision to continue or not in the blog depended on participation in different strategies: forums, e-mail, virtual consultations, reference topics, chats, and telephone follow-ups. In this study, some issues limiting the adoption of blog use other than care giving, were going to medical appointments (their own or that of the patient) and attending to leisure activities and family meetings. It was not possible to determine the personal factors underlying the lack of adoption of some FCs; however, the chat and the forum were the most consistently accepted strategies while reference materials were accepted to a lesser extent.

Other nursing theories can contribute to a better understanding of the results. In an investigation by Brennan, Moore, & Smyth (1991), results were limited in comparison with this study because the ICT examined in this study not only provides emotional support but also has a direct influence on how knowledge is acquired regarding an individual with a chronic illness. The concerns of the FC were not limited to searching for information on diseases but included a social space to be recognized as human beings, both for remembrance as well as and to regain their identity.

As for LaCoursiere's (2001), mid-range theory there is greater affinity in the validation of the results. The main phenomenon of this theory is the "interaction between people" rather than the exchange of information, which is consistent with the results in the interaction dimension. This perspective reveals that there is a cognitive and perceptual background that depends on online social support. In search of the deepest connection, FCs who adopt ICT- (Rogers 1983) become more experienced (the experience dimension) and begin to feel able to support others (Benner 1984). In this theory, the concept of the meta-paradigmatic environment is a virtual approach, and that of nursing is a part of cyberspace (the concept of pan dimensionality; M. Rogers 1992). The counselor who described the FC's participation is simply a facilitator who must also have thoughts and behaviors of online social support. At this point, it is useful to reflect on the technological competence for care proposed by Locsin (2009), the goal of which is to increase the understanding of technology and capture genuine care, defined as "a reflection of change, belief and commitment that a professional nurse makes with each person having an autonomous act with personal commitment and intention . With this perspective, we begin to think that the role of the nurse regarding online social support is geared towards what we refer to as Telenursing, which is an innovation in nursing care that integrates knowledge with social practice. Based on the analysis of the blog concept about disease proposed by Heilferty (2009), a proposal on the mid-range theory of online communications on disease states that this strategy corresponds to the background, attributes, and consequences of the concept. In it, narratives are paramount to the concept, and although they were not the main focus of this study, such narratives were reconstructed from reference topic of care experiences, which were provided by the FC as feedback. Similarly, their participation was strengthened by the caregiver's recognition (resulting from the use of blogs) of the "Evolution of Identity , feeling welcome to a virtual space, and feeling supported when they post messages, feelings, or words of encouragement to other FCs or when uploading their faces with a personal photo. Heilferty (2009), represented interaction was as another dimension with the author-reader interaction improving the relationship and reducing isolation.

Finally, it is worth noting that this study provides and acknowledges the need to continue developing nursing knowledge in the context of ICT as a central element in FC care. There are weaknesses in terms of the access and availability of technological resources, but clear concepts were identified in this study in favor of defining the role of nursing in the social network as a facilitating agent rather than as part of the social support network. It is the duty of the nurse to provide care that is innovative in outlook, so it is expected that work with mid-range theories, which are still not well understood in the context of Colombia, will continue.

References

1. Armayones, M., Sánchez, C.L. (2011). New technologies, new players (21-46). In: Salcedo, V.T., Luque, L.F. (2011). The ePatient and social network health 2.0. ITACA-TSB, Polytechnic University of Valencia - Spain. Publidisa. Accessed July 18, 2011. Available at http://bit.ly/rp9Fft

2. Barrera, L., Galvis, C. R., Pinto, N., Moreno, M., Pinzón, M., Romero, E., et al. (2006). The ability to care for family care-givers of people with chronic illness Research and nursing education, 24(1),36-46.

3. Barrera L, Pinto N, Sánchez B (2007). Resarch network Network of Researchers on Caring for Chronic Patient Caregivers. Aquichan, 7(2): 199-206

4. Barrera L, Pinto N, & Sánchez B (2008). The construction of the care model to caregivers of people with chronic illness. Actualizaciones en Enfermería, 11(2): 22-28.

5. Barrera, L., Pinto, N., & Sanchez, B. (2010). Chronic disease. In: Barrera, L., Pinto, N., Sánchez, B., Carrillo, G., & Chaparro, L. (Eds). Taking care of family caregivers of people with chronic disease. Bogota: Unibiblos.15-24.

6. Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

7. Brennan, P.F., Moore, S.M., & Smyth, K. A. (1991). ComputerLink: Electronic support for the home caregiver. Advances in Nursing Science, 13(4):14-27.

8. Cobb, S. (1976). Social Support as a moderator of life stress. Quoted in: Lindsey, A., & Yates, B. (2003). Social Support: Conceptualization and Measurement Instruments. In: Sharon, O. (2004). Instruments for Clinical Health Research. 3rd ed. Jones and Barlett Publishers Canada, 12; 164-196.

9. Ferguson, T., & Frydman, G. (2004). The first generation of e-patients. BMJ, 15(328)(7449), 1148 -1149.

10. Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2005). Clarification of Social Support. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 37(1), 4-9.

11. Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2007). Concept Comparison of Caring and Social Support. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 18 (2), 58-68.

12. Heilferty, C. M. (2009). Toward a theory of online communication in illness: concept analysis of illness blogs. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65: 1539-1547.

14. Hilbert, G.A. (1990). Social Support in chronic illness. Measurement of nursing incomes. Vol. 4. Measuring client-self care and coping skills. Springer Publishing Company, 79-95

15. Hinson, C.P., Bowsher, J., Maloney, J.P & Lillis, P.P. (1997). Social support: a conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(1), 95-100.

16. House, J.S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Quoted in: Lindsey, A., Yates, B. (2003). Social Support: Conceptualization and Measurement Instruments. En: Sharon, Olsen. Instruments for Clinical Health Research. 3rd ed. Jones and Barlett Publishers Canada, 12; 164-196

17. Hupcey, J.E. (1998). Social Support: Assessing Conceptual Coherence. Qual Health Res, 8; 304-318.

18. Kane, R., Priester, R., & Totten, A. (2005). Meeting the Challenge of Chronic Illness. Johns Hopkins University Press. 303, 23-42.

19. Kernisan, L., Sudore, R. L., & Knight, S.J. (2010). Information-Seeking at a Care-giving Website: A Qualitative Analysis. J Med Internet Res, 12(3): e31. Accessed July 18, 2011. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2956334/

20. Kerr, C., Murray, E., Stevenson, F., Gore, Ch., & Nazareth, Irwin. (2006). Internet Interventions for Long-Term Conditions: Patient and Caregiver Quality Criteria. J Med Internet Res, 8(3): e13. Accessed July 18, 2011. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1550703/

21. Klemm, P & Wheeler, E. (2005). Cancer Caregivers Online: Hope, Emotional Roller Coaster, and Physical/Emotional/Psychological Responses. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 23(1), 38-45.

22. LaCoursiere, S. P. (2001). A Theory of Online Social Support. Advances in Nursing Science, 24(1), 60-77.

23. Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. 1985.

24. Lindsey, A., & Yates, B. (2004). Social Support: Conceptualization and Measurement Instruments. Sharon, Olsen. Instruments for Clinical Health Research. (3rd ed). Canada: Jones and Barlett Publishers, 164-196.

25. Locsin, R. (2009). "Painting a clear picture": Technological Knowing as a contemporary nursing process. In Locsin R., Purnell, M. A contemporary Nursing Process. The (Un) bearable weight for knocking in Nursing. Springer, Co. New York.

26. Nadal, J. (2007). The ICT and future sanity. Journal Bit, 36-40. Accessed July 18, 2011. Available at: http://www.coit.es/publicaciones/bit/bit163/36-40.pdf

27. National University of Colombia. Atlas ti. Version 6.0.12. [Computing Software]. Educational License Site. Bogota.

28. Newman, M. (1994). Health as expanding consciousness. National League for Nursing Press. 2nd ed. New York, pp 145.

29. Pan American Health Organization(2007). Regional strategy and action plan for an integrated approach to prevention and control of chronic diseases. Washington, USA.

30. Peña, J.L. (2004). Information and Communication Technologies. Medical Education, 7(2), 15-22.

31. Pierce, L., Steiner, V., & Govoni, A.L. (2002). In-home Online Support for Caregivers of Survivors of Stroke: A Feasibility Study. Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 20(4): 157-164

32. Pinto, N., & Sánchez, B. (2000). The challenge for family caregivers of people experiencing chronic disease. Nursing care and practice. Care Group. School of Nursing. National University of Colombia (pp. 172-179). Bogota: Unibiblos.

33. Ramos, V. (2007). The ICT in the health sector. Journal Bit, 41-45. Accessed July 18, 2011. Available at: http://www.coit.es/publicaciones/bit/bit163/41-45.pdf

34. Rogers, M.E. (1983). Diffusion of innovations theory. 3rd ed. New York.

35. Rogers, M.E. (1992). Nursing in the space age. Nurs Sci Q, 5:27-34

36. Schachinger, A. (2010). Healthcare Digital: Status Quo and Development. 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5tOngklbOHON. Health on the Net 2010. Accessed July 18, 2011. Available at: http://www.health20eu.wordpress.com/uber/

37. Sullivan, C.F. (2008). Cybersupport: Empowering Asthma Caregivers. Pediatric Nursing, 34(3): 217-224.

38. Struk C, Moss J (2009). Focus on Technology: What Can You Do to Move the Vision Forward?.Computers Informatics Nursing, 27(3) 192-194.

39. The United Nations Organization. (2010). Millennium objectives development. 2010 REPORT. New York.

40. Torrente, E., Escarrabill, J., & Martí, T. (2010). Impact of social networks of patients in clinical practice. Journal of Health and Integrated Innovation, 2 (1), 1-8.

41. Tilden, V.P. (1985). Issues of conceptualization and measurement of social support in the construction of nursing theory. Research in Nursing and Health, 8: 199-206. Quoted by: Hupcey, J.E. (1998). Social Support: Assessing Conceptual Coherence. Qual Health Res, 8; 304-318.

42. Vélez. J. (2010). Regulations, applications and challenges for electronic health in Colombia. In: Fernández, A & Oviedo, E. Electronic health in Latin America and Caribbean: Progress and Challenges. CEPAL and European Union. Accessed July 18, 2011. Available at: http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/5/41825/di-salud-electrinica-LAC.pdf

43. Vrabec, N.J. (1997). Literature Review of Social Support and Caregiver Burden, 1980 to 1995. Image Journal Of Nursing Scholarship, 29(4), 383-388.

44. Williams, P., Barclay, L., & Schmied, V. (2004). Defining Social Support in Context: A Necessary Step in Improving Research, Intervention, and Practice. Qual Health Res, 14; 942-960

45. Weiner C, Cudney S, Winters C. (2005) Social Support in Cyberspace. The next Generation. Computers Informatics Nursing, 23(1): 7- 15

Acknowledgments

The Research Division of Bogota (DRB) at the National University of Colombia is acknowledged for funding this study under project code 9567 for 2009-2011. The CF program "Caring for the caregivers" is also acknowledged for their participation in the project and for sincerely expressing their opinions.

We'd like to give a special mention to Mrs. Natividad Pinto, professor and leader of the chronic patient care investigation group and her family. Mrs Pinto sadly passed away earlier this year, but actively supported the investigation process for this article.