Articles

Alicia

Elizabeth Hermosilla-Ávila 1

Olivia Inés Sanhueza-Alvarado 2.

1 ![]() 0000-0002-5532-1755 Department

of Nursing, Universidad del Bío Bío, Chile. ahermosilla@ubiobio.cl

0000-0002-5532-1755 Department

of Nursing, Universidad del Bío Bío, Chile. ahermosilla@ubiobio.cl

2 ![]() 0000-0002-0184-8957 Faculty of Nursing, Universidad de Concepción, Chile. osanhue@udec.cl

0000-0002-0184-8957 Faculty of Nursing, Universidad de Concepción, Chile. osanhue@udec.cl

Received: 15/02/2019

Sent to peers: 19/03/2019

Approved by peers: 28/05/2019

Accepted: 12/06/2019

10.5294/aqui.2019.19.3.3

Theme: Chronic care.

Contribution to the discipline: Nursing professionals, during the care of patients with chronic pathologies, broaden and use healthcare networks to generate synergies and improved care processes with which they strengthen the permanent contact with the family and the individual. In this process, the ethical commitment with humanization is continuous; individuals are evaluated in their entirety: in their family, social, economic, and work environment, which permits guiding healthcare efficiently to improve the quality of life of individuals with advanced cancer and their families. Quality care is combined with the incorporation of technological elements, which, far from dehumanizing, contribute to the patient-family-nursing professional transpersonal relationship. Permanent humanized accompaniment favors the management of people-centered care, with emphasis on palliative care, interventions aimed at the particular wellbeing of the individuals and their families, based on theoretical-humanistic foundations, through the application of a nursing process with individualized assessment and diagnosis, which contributes to international health objectives, aimed at improving the quality of life of the person with cancer and of the family caregiver, in spite of the inevitable progress of the disease.

Para citar este artigo / Para citar este artículo / To reference this article: Hermisilla-Ávila AE, Sanhueza-Alvarado OI. Intervention of Humanized Nursing Accompaniment and Quality of Life in People with Advanced Cancer. Aquichan 2019; 19(3): e1933. DOI: 10.5294/aqui.2019.19.3.3

|

Abstract Objective: To assess the effect of an intervention of humanized

nursing accompaniment, at home, on the quality of life of people with advanced

cancer and of their family caregivers. Keywords (source DeCS): Neoplasia; quality of life; nursing care; hospice care; intervention. |

Resumen Objetivo: evaluar el efecto de una intervención de

acompañamiento humanizado de enfermería en domicilio, en la calidad de vida de

las personas con cáncer avanzado y su cuidador familiar. Palabras clave (fuente DeCS): Neoplasia; calidad de vida; cuidado de enfermería; cuidado de hospicio; intervención. |

Resumo Objetivo: avaliar o efeito de uma intervenção de acompanhamento humanizado de enfermagem em domicílio, na qualidade de vida das pessoas com câncer avançado e cuidador familiar. Palavras-chave (fonte DeCS): Neoplasia, consciência de vida, cuidado de Enfermagem, cuidado no hospício, intervenção. |

Introduction

Current demographic, epidemiological, and lifestyle changes in Chile have brought – as a consequence – an increased number of people with cancer diagnosis. Economic, social, and cultural factors influence upon the incidence of cancer and its survival (1), as well as an increase in the average costs related with its care (2, 3). Such impact, provoked by this pathology at national and global scales, has increased concern for improving the conditions and quality of life of the people suffering this disease, which has validated the health area as an enhancer link of the quality of life of people.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that at least 30-million people globally suffer unnecessarily severe pain and other symptoms due to cancer, which obligates countries to create comprehensive programs to control the disease (4). In 1980, the WHO incorporated palliative care as part of cancer control, arguing that it improves the quality of life of patients and the families confronting problems associated with life-threatening diseases, through prevention and relief of suffering, through early identification and evaluation and treatment of pain and other physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems. Although many countries have incorporated it in their health systems, in Latin America its coverage is still from 10 % to 12 %, in urban zones, and at 0 % in rural zones, except for countries, like Chile, where the coverage is almost at 99 % (5, 6).

In this respect, the International Nursing Council has established that the nursing function is fundamental to provide palliative care aimed at reducing suffering and improving the quality of life of people during their last days of life, as well as that of their families. Said care must include early assessment, identification, and management of pain and of the physical, social, psychological, spiritual, and cultural needs (7), equivalent to worrying for the subject’s experience (8), approached from a multidimensional perspective (9).

Cancer, due to its seriousness and because it constitutes a disease stigmatized and feared by the population – added to the suffering it causes to those who endure it and to their loved ones – brings as consequence numerous alterations throughout the family structure (10), and this makes necessary numerous and complex care, as well as participation from the whole health staff. Caregivers experience an intense overburden, with severe repercussions. By having to commit to caring, on average, for 13 or more hours per day, their psychological wellbeing is considerably affected; thus, presenting depression, anxiety, and lack of satisfaction in fundamental areas of their personal and family life (11,12).

From home nursing care, it becomes necessary to search for and evaluate new ways of supporting the care of people with advanced cancer, as well as their families; ways that promote humanized treatment, with moral commitment and of protection to human dignity, under conditions of crisis or vulnerability. Due to the aforementioned, this research sought to evaluate the effect of an intervention of humanized nursing accompaniment at home on the quality of life of people with advanced cancer and of their family caregivers.

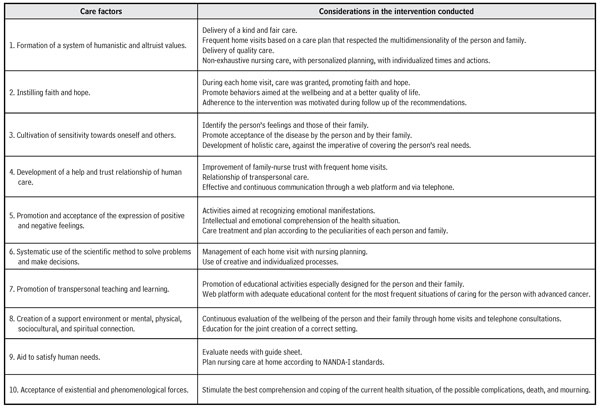

It is fitting to add that the scope of this intervention was planned based on the theoretical framework that supports the research, specifically in its connection with the factors of humanized care developed by Watson, as specified in Table 1 (13,14):

Table 1. Care factors and supports of the intervention

Source: Own elaboration based on the care factors by J. Watson (15).

Method

The study used a pre-experimental design of pre- and post-intervention in an intact group, conformed previously by users registered in a primary care health service of palliative care with diagnosis of advanced cancer, subjected to pre-intervention measurement, which provided baseline and control scores and of such. In the end, a post-intervention measurement was conducted, with the same instruments used in the baseline measurement, and with the analysis of the scores obtained pre- and post-intervention.

The sample was comprised by an incidental sampling of all the users registered, over 18 years of age, in the palliative care service, together with their principal caregivers. The sample collection and authorization for the research were approved by the Ethical-Scientific Committee of the regional health service, guaranteeing protection to patients’ rights and considering the ethical aspects referred by Exequiel Emanuel (16). The study excluded those who, due to their physical or cognitive circumstances, were not in conditions to understand or answer the collection instrument; those who non-relative caregivers or caregivers who were paid; and those who refused to participate. Once obtaining the informed consent, 17 patient-caregiver dyads completed and concluded their participation in the study, remaining for three months in the intervention of humanized nursing accompaniment.

The meetings among the researcher, the families and their patients took place within the context of the home, where the study’s baseline or control measurements were collected. The 17 participating dyads were applied sociodemographic and health questionnaires, and questionnaires on quality of life related with health, previously validated at national scale: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-30) (17), applied to people with cancer diagnosis, and the World Health Organization’s Abbreviated Quality of Life (WHOQOL-Bref) (18), applied to the family caregivers. These questionnaires were applied with an initial measurement – upon entering the study – and a final measurement – three months after the nursing intervention of humanized accompaniment, an intervention described ahead. Similarly, the reliability of the questionnaires was again determined to corroborate them in the context of the study, through Cronbach’s alpha, estimating high reliability for values close to 1, and low reliability for those below 0.5 (19).

In the data analysis, with the object of a better description and discussion of the results of quality of life, each dimension and global score was standardized to a scale from 0 to 100, where the result fluctuates between worse quality of life, for scores close to 0, and better quality of life, for those values close to 100.

To test the study hypothesis, the information was analyzed through comparison of medians for Student’s t test, for a related sample in those variables with normal distribution, and comparison of distribution trends with the Wilcoxon test, in the non-parametric variables, especially to measure differences between the pre- and post-intervention, which determined significant differences for p ˂0.05, and highly significant for values below 0.01.

Finally, to know the magnitude of the effect of the intervention on the quality of life on the dyad, the study tested statistically the quantification of the relevance of the effect obtained (small, moderate, or large) in this variable, through Cohen’s d, which represents the number of typical deviations separating the pre- and post-intervention measurements, in each dimension evaluated by the quality-of-life questionnaires, both in those applied to the person with cancer diagnosis, as in those conducted with the family caregiver, where the small effect size considers a Cohen’s d of 0.2; the moderate effect with 0.5; and the large effect with 0.8 (19).

Intervention of humanized accompaniment

The general objective of the intervention was to grant humanized nursing care accompaniment in the home. There was emphasis on covering the multidimensional and particular needs of the person with cancer and their family, through home visits; training the family caregiver on seeking palliative care from the nursing setting required by the person with advanced cancer; teaching care according to the needs of the person with advanced cancer, through audiovisual material available in the internet platform; and constantly providing humanized accompaniment, promoting affective communication, in person and on the telephone, once per week, with the person with cancer or their family.

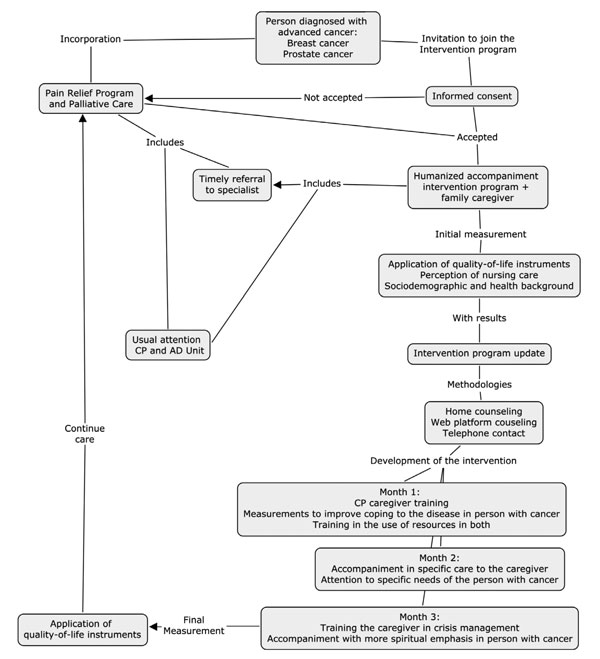

The accompaniment intervention gathers teaching-learning didactic strategies that complement the habitual care of the government programs received by people with advanced cancer and their families in the Pain Relief and Palliative Care Program. Figure 1 shows the protocol implemented with the care themes addressed per month, besides their connection with the program to which they belonged.

Figure 1. Intervention protocol

Source: Own elaboration.

Each counseling session was conducted through the personal interview, as method to communicate the information, contents, attitudes, and behaviors to the patient with cancer and to the family caregiver principal —as well as of teaching-practice—, promoting participation, adaptation of the contents to the family preferences or needs, with continuous interaction, based on the nurse-patient-caregiver transpersonal relationship by Jean Watson (15).

In addition, the intervention was supported by audiovisual contents, through an internet platform adaptable to web format web, tablet and mobile, to provide general information and specific aspects requested by the patients and their caregivers with respect to specific nursing care, in the person with advanced cancer, and of self-care, for the family caregiver. Mobile telephone service was incorporated, to solve unforeseen inquiries, and a notebook, as registry to perfect individualized nursing plans. To strengthen the humanized nursing accompaniment, three principal methodologies were used:

Nursing counseling at home – to reduce the emotional impact in people and their families upon situations of crisis associated with the diagnosis of advanced cancer; create communication spaces within the family; promote adherence to treatment; help to control and approach problems and specific needs in the person with advanced cancer, as well as care provided by the family and approached from the nursing perspective.

On-line counseling with educational platform – destined to become a support audiovisual tool in care during the final process of life. It is material in which the most frequent general nursing care is visualized to accompany people with advanced cancer.

Telephone contact – destined to strengthen interpersonal communication, secure the person with cancer-caregiver-nursing professional transpersonal relationship and remote accompaniment.

Nursing counseling was carried out through three home visits per month per family, to address themes according to that evaluated in each, during a three-month period. Planning of activities was specific and bounded to the family reality; many activities focus only on some of the aspects of palliative care, which established dynamic and changing counseling in each visit, and even in each moment during the visit. In each visit, an initial evaluation was made, according to the global context of the person and of their family, through nursing diagnoses detected in people with advanced cancer, like pain, spiritual suffering, risk of falling, risk of pressure ulcers, immobility, alteration of nutrition, dehydration, among others, with objectives in the short term. Care was executed and delegated to the relative in charge, according to priorities, with subsequent direct evaluation, and finally, evaluating each care in the process and result (20-22).

Results

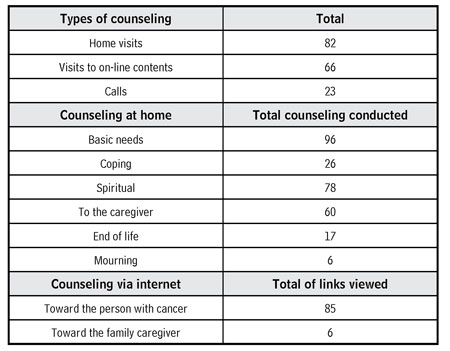

Table 2 describes the total number of interventions and counseling conducted, according to the requirements of the people with cancer and their caregivers, after performing the nursing evaluation and diagnosis.

Table

2. Operative characteristics of the intervention of

humanized accompaniment toward people with diagnosis of

advanced cancer and

family caregivers

Source: Own elaboration.

Participant profile

Of the 17 people with cancer diagnosis participating in the research, most were adults over 65 years of age, female sex, pensioned, without a partner, catholic, and sharing their home as nuclear family. Most knew of their cancer diagnosis –advanced or terminal– and had no chronic diseases –before or after entering the program–. With respect to their educational level, they were homogenously distributed into basic, medium, technical, and university.

Regarding the general state of the people with advanced cancer, the scale of Performance Status revealed that one third of the users had slight symptoms of the disease and were self-sufficient, while most already had prostration signs: They rested at least half of the day and needed occasional, partial, or total care from the family and nursing. The majority took pain medication, required no drugs to sleep, or some natural supplement.

Regarding the family caregivers, most of these were adult women over 65 years of age, pensioned, with a partner, with middle schooling, catholic, and completely autonomous in the daily care of the person with advanced cancer. They showed no presence of pain, and, although practically half had chronic disease, only a fraction adhered to the medication indicated for their disease.

Pre-intervention results

Prior to the intervention, health-related quality of life of people with diagnosis of advanced cancer, in the global health subscale, had a medium score, without inclination to a low or to a high valuation, while the dimensions with lower quality of life were related with the emotional role, evidenced by the perception of feeling worried, nervous, irritated, or depressed, along with the cognitive function, in the levels of concentration and memory. The symptoms with high score, referred to poor quality of life and related with the pathology, were fatigue and dyspnea. In this measurement, the questionnaire had high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.892).

In the family caregivers, the measurement approached, mostly, valuations of very good global quality of life and very satisfactory global health. The dimension of physical health had the best quality profile and social relationships had the worst assessment. In this measurement, the questionnaire had high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.936).

Post-intervention results

During three months, the intervention of

humanized nursing accompaniment contemplated the three counseling modalities

(home visits, visits to on-line content, and telephone calls) to contact the patient

and the relative in charge, to satisfy the basic and spiritual needs of the

people with diagnosis of advanced cancer. Even when numerous interventions were

conducted to support the care provided by the caregiver at home, visits to

on-line resources were mostly to consult the contents of caring for the person

with cancer.

At the end of the intervention, the measurement of quality of life related with the health of the people with diagnosis of advanced cancer resulted aimed at the better quality of life in the global health scale, given that some symptoms related with the pathology diminished, such as fatigue, dyspnea, and pain, without gastrointestinal discomfort. The social function also obtained high quality of life. Two dimensions had low quality of life, specifically the emotional role and the cognitive function.

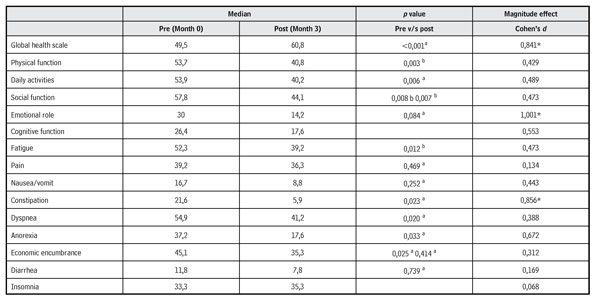

When comparing the pre- and post-intervention results of quality of life and the evolution of the effect of the intervention of humanized nursing accompaniment of people with advanced cancer (Table 3), since the initial month to the final month, there was highly significant improvement in the global health subscale, an evaluation that measures the perception toward health and quality of life, and an effect of large magnitude. Likewise, improvement existed in relation with the symptom of constipation, with a significant difference and an effect of large magnitude. Also, the person’s perception of all the symptoms related with cancer diminished with significant differences for fatigue, dyspnea, and lack of appetite.

Table 3. Comparison of quality of life related with the health of people with diagnosis of advanced cancer – EORTC QLQ – C30

a with Rank test with Wilcoxon sign.

b with Student’s t test of related samples.

* Large magnitude of the effect.

Source: Own elaboration.

Pre- and post-intervention comparison of the family caregivers permitted evaluating the effect of the intervention of humanized nursing accompaniment on their quality of life, and demonstrated improved global quality of life, as well as that of global health, although the difference was not statistically significant. Psychological health showed improvement, with moderate increase, a significant difference and best quality profile: Desires of enjoying and of giving sense to life were observed, as well as decreased negative feelings. Regarding the dimensions of social relationships and the environment, referring to the valuation of leisure, information available, housing conditions, health service, and transportation, improvement was also observed; and the increase in quality of life was statistically significant.

Discussion

The study results confirm that palliative care health units play a fundamental role, in technical elements as in their human elements (23), which they must provide to the patient-family caregiver dyad. It was noted that they require peremptorily of what Watson denominates “care factors” (15). In the process carried out, the ethical compromise with humanization was permanent, based on factor 4 of caring, that refers to developing a relationship of help and trust of human care, which values people entirely, in their family, social, economic, and work environment, permitting to guide care efficiently to improve the quality of life of people with advanced cancer and of their family.

The technological elements incorporated contributed to the patient-family-nursing professional transpersonal relationship, given permanent communication. Humanized accompaniment was also based on factor 2 of caring by Watson (15), which calls to instilling faith and hope during care, which was provided at all times. Factor 6, related with the systematic use of the scientific method to solve problems and make decisions, was established by applying the nursing process with individualized assessment and diagnosis, which favors the management of people-centered care, with emphasis on palliative care and interventions aimed at the particular wellbeing of the individuals and their families, based on theoretical-humanist foundations.

Care factors 7, 8, and 9 (15) were applied via the promotion, throughout the process, of transpersonal teaching and learning, creating an environment of support or mental, physical, sociocultural, and spiritual connection to aid in the satisfaction of human needs. The principal objectives of palliative care, at national and international scales, are aimed at improving the quality of life of patients and their families (4, 5, 7, 24), urging professionals to satisfy the needs that emerge during advanced cancer, as well as to take over the multidimensional nature of caring. This study tried to relieve these characteristics in the intervention conducted, providing dynamic and flexible nursing care, from the individualized approach of the experience (4), which improved global health and diminished the perception of all the symptoms related with cancer by the person with cancer, with significant differences for fatigue, dyspnea, lack of appetite, and constipation.

Unlike other studies, the research shows that people with cancer continue maintaining a medium evaluation of quality of life in the dimension of social function. The diagnosis of advanced cancer, and the subsequent incorporation to palliative care, is probably the start of a process of personal and family suffering, marked by the proximity of a person’s last days of life. On comprehending this process, it was considered that factor 10 of caring (15), related to accepting existential and phenomenological forces, stimulates better comprehension and coping with the current health situation, of the possible complications, death and mourning, in combination with the perception of having a unique and transcendent time space for the patient and the family. This could have generated a very valuable accompaniment experience, as long as patients receive timely implementation of care, given that they are in a situation of suffering and pain —in all the dimensions that define the human being— which profoundly touches their family and close relatives.

In the global dimension, the quality of life of family caregivers was quite good, and in most of the dimensions with a medium to good score. The lower figure occurred in the dimension of social relationships, a similar score estimated by another study (25), although with a lower evaluation to general quality of life. That same study evidences, in the specific case of family caregivers of dependent patients, poor or very poor quality of life in higher percentages, from the subjective evaluation of such. Said values are significantly related with the spheres of energy, sleep, social relationships, and emotionality.

With respect to the low valuation obtained in the social dimension, another study highlights lack of support in care, anguish associated with their caregiver role, and obstacles presented by caring for their personal relationships and those of the home. With respect to the home, a higher economic burden is mentioned (26).

Even when relatives openly manifest enjoying activities that allow them to disconnect from the considerations of the diagnosis and the prognosis, they recognize the importance of the support offered by other people, but –likewise– not requesting aid for care (27).

Another dimension of importance, revealed through the caregiver’s experience, is the psychological dimension, which denote the importance of its consideration when providing humanized care, established primarily by aperture upon the personal expectations and upon the manifest need of strengthening the bond, the communication, empathy, and accompaniment with the nursing professional. Another study states it similarly, according to which management of the psychological wellbeing is given by the coping strategies of the very patient and their family, including a realist, indulgent relationship of collective learning by the professional (28).

In general, there are scarce humanization interventions identified in the literature, aimed at people with advanced cancer, although many of the national and international health orientations seek to comply with objectives related with improving the quality of life of patients and their family caregivers. For their part, nursing professionals are responsible, in the health staff, for palliative care, which must be innovative, based on evidence and on the Theory of Humanized Care (15), in favor of the family quality of life, and destined to aid in a good death and to face the challenges of this stage.

Few countries have established specialized programs to provide pain relief and palliative care (5), even with the evidence that specific or specialized programs in palliative care seek to reduce suffering and raise the quality of life of patients and their families from the multidimensionality of their needs (6, 7, 9, 29).

The benefits of early palliative care prove to favor quality of life and the decrease of the intensity of symptoms, in comparison to people with advanced cancer who receive standard treatment. As with this study, this early care shows a small effect and coincides with the conclusion that, within the context of advanced disease and its limited prognosis, this increase is clinically relevant (30).

Conclusions

In the person with diagnosis of advanced cancer, after the intervention of humanized nursing accompaniment, which included specific nursing care, counseling delivered according to their basic needs, support in coping, spiritual strengthening, and support received through web and telephone resources, there was significant improvement and a large effect on quality of life and on the particular dimension of global health, which are observed in the diminished perception of all the symptoms related with cancer (fatigue, dyspnea, lack of appetite, and constipation).

Family caregivers, after the intervention with complementary counseling to the patient, plus those aimed at caring at the end of life and at grief, improved their quality of life in the dimensions of social relationships and the environment, with a moderate magnitude of the effect.

In spite of the progress of the disease towards states of deterioration and dependence, it was evidenced that humanized nursing accompaniment to people with advanced cancer and to their caregivers managed to increase, significantly, the quality of life of all those involved in the relationship of care, upon reinforcing and reaffirming the social, affective, spiritual, and communication areas in the patient-family caregiver dyad.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

1. World Health Organization. Cancer. Descried note nº297. WHO [Internet]. 2018. [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/

2. Chilean Ministry of Health. Department of Health Statistics and Information. Government of Chile [Internet]. 2019. [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: http://www.deis.cl

3. Cid C, Herrera C, Rodríguez R, Bastías G, Jiménez J. Assessing the economic impact of cancer in Chile: a direct and indirect cost measurement based on 2009 registries. Medwave [Internet]. 2016;16(7):e6509 [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. DOI: 10.5867/medwave.2016.07.6509

4. World Health Organization. Pain. WHO [Internet]. 2018. [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/tratamiento/efectos-secundarios/dolor/dolor-pro-pdq#cit/section_1.8

5. World Health Organization. Palliative Care. WHO [Internet]. 2018. [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/es/

6. Morales A, Cavada G, Miranda J, Ahumada M, Derio L. Eficacia del Programa Alivio del Dolor por Cáncer Avanzado y Cuidados Paliativos de Chile. Revista El Dolor [Internet]. 2013; 22 (59): 18-25. Available in: https://www.ached.cl/canal_cientifico/revista_eldolor_detalle2.php?id=181

7. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Guía de Práctica Clínica Alivio del Dolor por Cáncer Avanzado y Cuidados Paliativos 2017. MINSAL [Internet]. 2017. [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: https://diprece.minsal.cl/wrdprss_minsal/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Resumen-ejecutivo_Alivio-del-Dolor_2017.pdf

8. Portela P, Gómez F. Advanced prostate cancer and quality of life. Arch Esp de Urología [Internet]. 2018;71(3):306-314. Available in: https://aeurologia.com/article_detail.php?aid=7f1dc2e81a2445ffe92fb30f0794cf1b8f23e0b8

9. Bryant-Lukosius D, Valaitis R, Martin-Misener R, Donald F, Peña L, Brousseau L. Advanced Practice Nursing: A Strategy for Achieving Universal Health Coverage and Universal Access to Health. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem [Internet]. 2017; 25:e2826. [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. DOI: 10.1590/1518-8345.1677.2826

10. Fernández-Isla L, Conde-Valvis F, Fernández-Ruiz J. Grado de satisfacción de los cuidadores principales de pacientes seguidos por los equipos de cuidados paliativos. Semergen. 2016,42(7):476-481. DOI: 10.1016/j.semerg.2016.02.011

11. Segura I, Barrera L. A call to nursing to respond to the health care of people with chronic illness due to their impact on their quality of life. Salud Uninorte [Internet]. 2016;32(2):228-243. Available in: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0120-55522016000200006

12. Velasco J. Grijalva M, Pedraza A. Repercusiones del cuidar en las necesidades básicas del cuidador primario de pacientes crónicos y terminales. Med Paliat. 2015; 22(4): 146-151. DOI: 10.1016/j.medipa.2015.01.001

13. Olivé C, Isla M. The Watson model for a paradigm shift in care. Rev ROL Enferm [Internet]. 2015;38(2):123-128. Available in: http://www.e-rol.es/articulospub/articulospub_paso3.php?articulospubrevista=38(02)&itemrevista=123-128

14. Watson J. Love and caring. Ethics of face and hand--an invitation to return to the heart and soul of nursing and our deep humanity. Nurs Adm Q. 2003; 197-202. Available in: https://journals.lww.com/naqjournal/Fulltext/2003/07000/Love_and_Caring__Ethics_of_Face_and_Hand_An.5.aspx

15. Watson J. Watson’s theory of human caring and subjective living experiences: curative factors/caritas processes as a disciplinary guide to the professional nursing practice [Internet]. The United States, Denver: 2006 [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/tce/v16n1/a16v16n1.pdf

16. Ezekiel E. Siete requisitos éticos. ¿Qué hace que la investigación clínica sea ética? Siete requisitos éticos. Pautas Éticas de Investigación en Sujetos Humanos: Nuevas Perspectivas. Organización Mundial de la Salud. 2003: 83-95.

17. Skevington SM, Lofty M, O Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res [Internet]. 2004; 13(2): 299-310. DOI: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00

18. Espinoza I, Osorio P, Torrejón M, Lucas-Carrasco R, Bunout D. Validación del cuestionario de calidad de vida (WHOQOL-BREF) en adultos mayores. Rev Med Chile. 2011; 139: 579-586. DOI: 10.4067/S0034-98872011000500003

19. Moncho J. Statistics applied to health sciences. Advanced Health Care Collection. 8 ed. Barcelona: Elsevier; 2015.

20. Bethancourt Y, Bethancourt J, Moreno Y, Suárez A. Evaluation of psychological well-being in primary caregivers of cancer patients in the palliative care phase. Mediciego [Internet]. 2014; 20 (2): 7 screens [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: http://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/mediciego/mdc-2014/mdc142f.pdf

21. Alfaro-LeFevre R. Application of the nursing process: fundamentals of clinical reasoning. 8 ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

22. Granados G. Application of psychosocial sciences to the field of caring. Barcelona: Elsevier; 2014.

23. Santana J, Pessini L, Sá A. Desires of terminally ill patients: a bioethical reflection. Rev Enfermagem. [Internet]. 2015; 18(1):2850 [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: http://200.229.32.55/index.php/enfermagemrevista/article/view/9367

24. Beltrán-Salazar Ó. Attention to detail, a requirement for humanized care. Index Enferm [Internet]. 2015;24(1-2): 49-53 [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. DOI: 10.4321/S1132-12962015000100011

25. Velasco J. Grijalva M, Pedraza A. Repercusiones del cuidar en las necesidades básicas del cuidador primario de pacientes crónicos y terminales. Medicina Paliativa [Internet]. 2015; 22(4): 146-151. DOI: 10.1016/j.medipa.2015.01.001

26. Salazar-Montes AM, Murcia-Paredes LM, Solano-Pérez JA. Evaluación e intervención de la sobrecarga del cuidador informal de adultos mayores dependientes: Revisión de artículos publicados entre 1997-2014. Arch Med (Manizales) [Internet]. 2016; 16(1):144-54. Available in: http://revistasum.umanizales.edu.co/ojs/index.php/archivosmedicina/article/view/813

27. Puerto H. Quality of life in family caregivers of people undergoing cancer treatment. Rev. Cuid [Internet]. 2015; 6(2):1029-40 [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. DOI: 10.15649/cuidarte.v6i2.154

28. Walshe C, Roberts D, Appleton L, Calman L, Large P, Lloyd.Williams M, Grande G. Coping well with advanced cancer: a serial qualitative interview study with patients and family carers. Plos One [Internet]. 2017;12(1):e0169071 [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169071

29. Chilean Ministry of Health. Department of Non-Communicable Diseases, Cancer Unit. Technical Report 2009 National Program Pain Relief and Palliative Care. Ciudad: MINSAL;2009. [Cited 2019 Jan. 4]. Available in: http://www.redcronicas.cl/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=38&Itemid=234.

30 Zurita J. Cuidados paliativos tempranos para adultos con cáncer avanzado. Rev Conamed [Internet]. 2017;22(4): 195-196. Available in: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/conamed/con-2017/con174i.pdf