Article

Vanessa Almeida Maia Damasceno 1

Marisa Silvana Zazzetta 2

Fabiana de Souza Orlandi 3

* This study was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes). The first author was awarded a grant from this agency. This study was also funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil.

* Este artículo tuvo apoyo financiero de la Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes), por medio de una beca concedida a la primera autora, y del Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brasil.

* Este trabalho teve apoio financeiro da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes) em forma de bolsa de estudos, concedido à primeira autora, e do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brasil.

1 ![]() 0000-0002-3367-7996. Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil.

0000-0002-3367-7996. Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil.

2 ![]() 0000-0001-6544-767X. Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil. marisam@ufscar.br

0000-0001-6544-767X. Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil. marisam@ufscar.br

3 ![]() 0000-0002-5714-6890. Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil. forlandi@ufscar.br

0000-0002-5714-6890. Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil. forlandi@ufscar.br

Received: 17/02/2019

Sent to peers: 12/03/2019

Approved by peers: 13/08/2019

Accepted: 01/09/2019

Theme: Chronic care.

Contribution to the discipline: The caregiver is the central point in the treatment process and is directly linked to the patient. In this context, this study contributes by verifying their ability and/or competence of caring as this variable directly affects the treatment and quality of life of the patient. In the health field, developing the chronic patient’s care cycle based on an instrument adapted and validated for its context is relevant as it helps to analyze the caregiver’s aspects that directly imply the quality of care offered. Regarding teaching, the availability of assessment tools helps to train professionals, implement health and care research, and is essential for compiling preventive and treatment actions for family caregivers.

To reference this article / Para citar este artículo / Para citar este artigo: Damasceno VAM, Zazzetta MS, Orlandi FS. Adapting the Scale to Measure the Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases in Brazil. Aquichan 2019; 19(4): e1948. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2019.19.4.8

|

Abstract Objective: To translate and culturally adapt the Scale to Measure the Care Ability

of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases to the Brazilian context. Keywords (Source DeCS): Translation; cross-cultural study; cross-cultural nursing; needs assessment; assessment of health care needs; ability; aptitude; caregivers; Brazil. |

Resumen Objetivo: traducir y adaptar culturalmente la Escala para Medir la Habilidad de

Cuidado de Cuidadores Familiares de Personas con Enfermedad Crónica para el

contexto brasileño. Palabras clave (Fuente DeCS): Traducción; estudio transcultural; enfermería transcultural; evaluación de necesidades; determinación de necesidades de cuidados de salud; habilidad; aptitud; cuidadores; Brasil. |

Resumo Objetivo: traduzir e adaptar culturalmente a Escala para Medir la Habilidad de Cuidado de

Cuidadores Familiares de Personas con Enfermedad Crónica para o contexto

brasileiro. Palavras-chave (Fonte DeCS): Tradução; estudo transcultural; enfermagem transcultural; avaliação de necessidades; determinação de necessidades de cuidados de saúde; habilidade; aptidão; cuidadores; Brasil. |

Introduction

Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases (CNCD) can be defined as permanent or long-term. Due to pathophysiological changes, they are considered almost or totally incapacitating (1), and therefore can lead to a loss of income, physical dependence, the need for caregivers, among others (2).

A patient, in this condition, feels the changes caused by the disease, which in turn lead to a process of adaptation for the individual and his/her family, especially the family member responsible for caring for the patient (3).

Although the patient has health care assistance, he/she needs a caregiver. Most of the time, this caregiver is a family member, a woman, who is not paid and has no specific knowledge about the disease (4). It is important to emphasize that this caregiver’s daily life changes so that he/she can dedicate him/herself to caring for a loved one (5).

Family caregivers carry out a wide range of tasks related to activities of daily living, ranging from hygiene care, preparing food, household chores, giving attention, providing comfort, treatment, socialization, medication administration, following-up medical appointments, among other activities, such as managing finances (5).

The act of caring causes stress, mental and physical exhaustion, overload, and may even cause difficulties in performing the caring function, which affects the care provided and the carer’s life as a whole. In addition, there is a lack of people to provide physical, emotional, financial support and even technical treatment instructions (6).

Considering competencies and care skills, we can define competence as the performance of each individual for a given job and/or task. It relates to the knowledge aspect and the skills developed for such a function, but competence is not simply reduced to the knowledge aspect, it also involves one’s ability to initiate what is required, to assume and to take responsibility for it (7).

Competence needed for care involves several aspects, such as the ability to coordinate treatment, anticipating problems and strengthening the family’s emotional bond. As family caregivers acquire more knowledge and skills to deal with situations where care is needed, coping improves, which increases the quality of care (8).

The caregiver’s skill to care is his/her ability and experience in caring for people with chronic diseases (CD). For these authors, that skill that a caregiver needs to have to care a patient properly, comprises three dimensions: relationship; understanding; and life changes (9). In addition, the family caregiver is the person with the most responsibility for providing basic care to the family who is cared for, supporting both activities of daily living and participation and even decision-making about the patient (9).

At the National University of Colombia, the Chronic Patient Nursing Care Group has been investigating caregiver care skills since 2004. In 2006, Barrera (10) developed and validated the Care Ability Scale for Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Disease (Escala Habilidad de Cuidado de Cuidadores Familiares de Personas con Enfermedad Crónica, in Spanish), which contained 55 items. However, in 2014, after carrying out various studies (11-14) of the psychometric properties of this instrument, another version with 48 items was made available, which included relationship (23 items), understanding (17 items) and change in routine (8 items), and it was called the “Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases”.

The “relationship” dimension refers to the bond between the person being cared for and the caregiver, to help with guidance and attitudes, seeking support in situations where there is overload, restriction and dependence; The “understanding” dimension indicates the caregiver’s ability to understand the situation, organize what is required of him/her, and consider agility in terms of learning from the patient’s situation, as well as their behaviors and care skills in order to recognize and accept the disease and treatment process. “Change in routine” encompasses the ability to accept the changes brought about in his/her life by being a family caregiver and the personal reward for such an act (14).

In Brazil, there are instruments that assess the physical and emotional aspects of caregivers, but there are few studies which provide normative data for the Brazilian context that assess the care ability of family caregivers of people with CD (15). Thus, it is important to highlight that the translation and cultural adaptation of assessment instruments in different cultures make it easier to compare data in different countries (16).

Therefore, it is of utmost importance to provide an instrument which has been translated and adapted to the Brazilian context that investigates the care ability specifically of family caregivers of people with CD as these skills directly affect the treatment, as well as the caregivers’ lives.

Given the above, this research aimed to translate and culturally adapt the “Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases” to the Brazilian context.

Materials and Methods

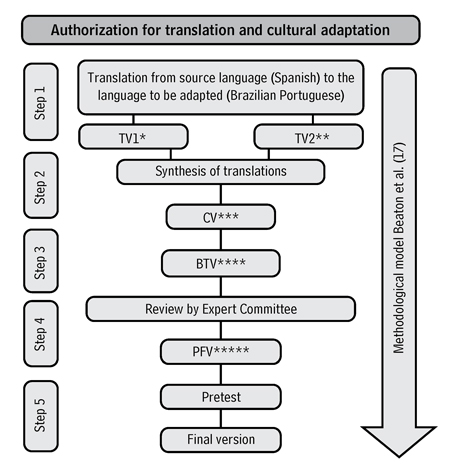

This is methodological research that aims to translate and culturallly adapt the Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases from Spanish into Brazilian Portuguese. This type of study requires previous planning of all the steps, since the translation and cultural adaptation process is carried out to have equivalence between the source language and the target language (16). The study followed the five steps suggested by Beaton et al. (17), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Scheme of the methodological model and the phases adopted in the translation and cultural adaptation process of the Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases

TV1 * (Translated Version

1), TV2 ** (Translated Version 2), CV *** (Consensual Version), BTV ****

(Back-translated Version) and PFV **** (Pre-Final Version)

Source: authors’ own work that followed the Guidelines for

the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures (17).

After formal authorization was granted by the author of the original instrument to develop the steps of the Brazilian version of the scale, which met the ethical and scientific rigor, the research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Carlos, under Report No. 1.435.698, and fully respected the recommendations of Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council from the Ministry of Health.

Translation and cultural adaptation included the following steps: initial translation; synthesis of translations and consensus; back-translation; review by a committee of specialists; and a pre-test.

The first step was carried out using the initial translation from Spanish (original version) into Brazilian Portuguese. This step was performed by two independent and qualified translators. Both met the necessary criteria for translation: proficiency in Spanish and mastery of Brazilian Portuguese. Both had expertise in health-related translations, knowledge of specific terms, and knowledge of the research objective. The translators were sent the original version and an explanatory letter; the translated version 1 (TV1) and translated version 2 (TV2) derived from this step.

The second step of the research included the synthesis of translations (TV1 and TV2) and the formation of the consensual version (CV), carried out between translators and researchers. In the third phase, a back-translation was done by a third translator who had expertise in the area and in Spanish. Confidentiality regarding the purpose of the research was maintained in order to avoid interference. Afterwards, the back-translated version (BTV) of the instrument was sent to the author, who approved it.

In the fourth step, cultural adaptation was carried out, which included content evaluation and cultural equivalence analysis. In this phase, a committee of specialists was formed comprising seven members, who all had PhDs and were university professors, working in research and/or with care experience to the caregiver and proficient in Spanish. After agreeing to be part of the Committee, an explanatory letter was sent to clarify doubts about the instrument and the requested analyses. Then, the instrument was analyzed as a whole and the pre-final version (PFV) of the instrument was done in Brazilian Portuguese.

In the fifth step, the PFV of the instrument was pretested on family caregivers of people with Chronic Disease; 14 family caregivers of people with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) on hemodialysis participated in the pretest. The study site was in a Renal Replacement Therapy Unit (RRTU) in the interior of the state of São Paulo. Data was collected between March and April 2017. The inclusion criteria were that they had to be: a family member of a person with CKD on hemodialysis of the referred RRTU; 18 years of age or older; the primary caregiver of the family member; and literate. All participants were interviewed individually in a private room of the RRTU after signing the Informed Consent Form.

Initially, the accompanying caregivers of the patients who were in the RRTU were asked about the degree of kinship with the patient. In addition, it was observed whether the caregivers met the inclusion criteria. Then, the research objectives were presented.

The interview included the application of three instruments. The first was a caregiver characterization questionnaire (sociodemographic information). The second was the pre-final version of the family caregivers’ care ability instrument for people with Chronic Disease, which was added to two columns in order to verify the clarity of the terms and to obtain suggestions. The third was a general questionnaire to assess the clarity of the instrument, adapted from Disabkids (18).

The collected data were entered in Excel for Windows and processed in the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software, version 20.0, in which descriptive analyses were performed regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of the pre-test participants.

The Content Validity Index (CVI) of the 48 items of the Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases in Brazil was also calculated. To this end, the judges (committee members) evaluated all items of the instrument on a Likert response scale, which ranged from one to four points. For the CVI analysis, we used the criteria proposed by Lynn in 1986 (18), which states that for six or more judges the expected value is above 0.78 (18).

Results

While translating the original text, which led to TV 1 and TV 2, translator 1 - only this translator had difficulty in the translation process - reported that in some questions of the original scale, the term “family member” was used, and in others the expression “sick family member” was used, hence it was not standardized. The other differences between the translations referred to lexicon, rection and verb tenses, and did not affect the content.

Next, the researchers, together with the translators, established the consensual version of the scale, which underwent a back-translation process by another translator. Following the process, the back-translated version of the Scale was forwarded to the author, so that she could verify the reliability to the original instrument, which was approved without objections. The author of the instrument did not make any objections and agreed with the version adapted to the Brazilian context.

The committee of specialists analyzed the instrument item by item, based on a Likert scale. When necessary, they suggested changes. Afterwards, the CVI was verified. From the 48 items evaluated, 41 items had CVI = 1.00, three items had CVI = 0.86 and four items had CVI = 0.71. In order to make the instrument available in a clear way which was easy to understand, items with a value lower than 1.00 were reviewed (Table 1), although it is recommended in the literature to review only items with CVI equal to or less than 0.78.

Table 1. CVI of the items of the Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases in Brazil adjusted by the Committee of specialists

Item |

Translated question |

CVI |

Revised question |

4 |

I worry that I cannot respond to my sick family member’s expectations. |

0.71 |

I worry that I can’t meet my family member’s expectations. . |

13 |

I felt that I cannot look after my sick family member. |

0.71 |

I feel I can’t take care of my family member. |

33 |

I am clear about what I will do with my life when I think of the death of my sick family member. |

0.86 |

I am clear about what I will do with my life when I think of the death of my sick family member. |

36 |

I value that life is important because of the experience I have gained from caring for my sick family member. |

0.86 |

I value the importance of life because of the experience gained from caring for my family member. |

41 |

I feel comfortable knowing how to fulfill my duty of taking care of my sick family member. |

0.86 |

I feel calm when I think I have a duty to care for my family member. |

44 |

The tasks of the people nearby have changed because they had to take care of my sick family member. |

0.71 |

The tasks of the people close to my family member have changed because they have to take care of him. |

47 |

I have applied what I have learned about care to my sick family member. |

0.71 |

I apply what I have learned about caring for my family member. |

Source: Own elaboration.

After the specialists, researchers and translators reviewed the instrument, the pre-final version of the scale was submitted to the pre-test. In the pretest, the sample consisted of 14 family caregivers of people with CKD, aged between 27 and 66 years, with a mean of 49.92 (SD = 11.11) years; mostly women (78.58 %), who were married (78.58 %) and had not finished elementary school (78.58 %) (Table 2).

Table 2. Sociodemographic and care characterization of family caregivers of people with CKD who participated in the pre-test. Sao Joao da Boa Vista, Sao Paulo, 2017

Characteristic |

Category |

Frequency |

% |

Gender |

Female Male |

11 3 |

78.58 21.42 |

Marital status |

Married Singles |

11 3 |

78.58 21.42 |

Education |

Did not finish elementary school Did not finish high school Did not finish higher education |

11 1 2 |

78.58 7.14 14.28 |

Lives with the family member he/she cares for |

Yes No |

7 7 |

50.00 50.00 |

Degree of kinship between caregiver and the family member being cared for |

Son/daughter Spouse Mother Brother/Sister |

8 3 2 1 |

57.14 21.42 14.30 7.14 |

Receives help for care |

Tes No |

11 3 |

78.58 21.42 |

The family member receives third-party financial resources |

Yes No |

5 9 |

35.71 64.28 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Regarding the time the caregiver takes care of the family member, it ranged from 3 to 96 months, with an average of 29.42 months (SD = 25.16). Regarding the time dedicated to care activities, it was observed that caregivers had an average time of 16.28 (SD = 8.34) hours per day, ranging from 5 to 24 hours per day (Table 2).

When applying the pre-final version of the scale, all participants rated the 48 items of the instrument as clear, and therefore did not suggest changes. Regarding the evaluation of the importance of the theme, as well as the clarity of the pre-final version of the instrument, through Disabkids’ general adapted clarity questionnaire (19), the participants considered the instrument very good (n = 7; 50 %) or good (n = 7; 50 %).

Regarding the degree of difficulty of the questions, 11 participants (78.57 %) indicated that all items were easy, while three (21.43 %) people answered that some items were difficult, but did not report the difficulties, and did not suggest any changes. Finally, we asked if the items were important to assess caregivers’ perceptions and experiences, and most respondents considered them to be “very important” (n = 13; 92.86 %), while only one respondent replied that “it is important sometimes”.

Although all the participants did not suggest changes to the items, when the pre-test of the instrument was applied, the interviewer observed that it was difficult for some caregivers to understand the verb tense adopted in the items. Thus, the items on the scale were analyzed again, making the verb tense of the items uniform with the predominant adoption of the present tense.

Discussion

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation processes of measuring instruments are delimited in methodological studies and, in general, are complex because they require, besides the literal translation of words, adapting them culturally (19). This process also includes making semantic, idiomatic, experimental and conceptual equivalences (20).

Based on studies by Beaton et al. (17), in this research, the recommended methodological steps were developed for the cultural adaptation of the measurement instruments, as they are effective for developing the translation, adaptation processes and validating the measurement scales (17). In the Brazilian study conducted by Rosanelli, da Silva and Gutiérrez (15), the translation, adaptation and validation of the Caring Ability Inventory (CAI) into Portuguese were developed. In this study, the authors adopted the same methodology proposed by Beaton et al. because it is a consolidated process and very usual for this type of research (21).

In order to seek high quality standards, it is recommended that the translation be performed by two independent translators who are qualified for this activity and, preferably, both from the country of origin of the instrument to be carried out, therefore, the professional is expected to be proficient in the language, know the culture and have clear concepts. The consensual version of the scale is performed to solve possible divergences or ambiguities (22).

Back-translation is the part of the process that aims to improve the final version and identify translation flaws. The aim of reverse translation is to refine the instrument, and the translator of this step must be fluent in both languages, that is, fluent in the source language of the instrument and into which it will be adapted (23).

Thus, it is clear that the steps developed in the present study (translation, synthesis of translations and back-translation of the Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases in Brazil) were properly developed.

In order to reach the pre-final version of the instrument, the formation of the committee of specialists was indispensable, aiming to revise and compare the translations, as well as the consensual version, modifying and adapting it until a replica of the instrument was obtained in Brazil. The specialists must master the instrument’s source language and have expertise in the area of health with experience in the theme studied (23).

Therefore, in the present research, the committee of specialists had seven members who fulfilled the attributions mentioned in the method. The specialists had to evaluate the instrument generally and individually, verifying it item by item, which ensures that the pre-final version is clear and understandable to the culture. The judges should also suggest and guide changes in the context of the instrument (23, 24).

The CVI verifies the number of judges who agree that the items analyzed in the instrument are clear/equivalent/representative. The calculation is made based on the Likert answers, in which items that obtained answer 1 and/or 2 must be reviewed or excluded, and items with score 3 and/or 4 must be calculated based on the sum of each judge’s answers in each item divided by the total number of answers, with the recommended agreement value greater than or equal to 0.78 (23).

The instrument of the present research consists of 48 items; from these, seven had CVI <1, which were reviewed despite only four items reaching CVI <0.78 (18). A study conducted by Blanco-Sánchez et al. (14), in Colombia, aimed to verify the content validity of the Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases in Brazil and was attended by 10 specialists. They were selected considering academic background and experience. Nine were nurses, two of them had doctorates in nursing, three had a master’s degree with vast experience, one had a master’s degree and experience in constructing and validating measurement instruments, three doctoral students in nursing, who studied the subject in more depth, and one psychologist who had a master’s degree in education and teaching, with experience in clinical psychology, and psychometric measurement of psychological assessment. During the content validity analysis, the Kappa de Fleiss global value, which was 0.78, was verified, which shows a good agreement among the experts and shows that the Barrera scale has content validity, that is, the specialists report that most items are clear and measure what they propose to (14).

After reviewing the scale items in the adaptation process, considering the specialists’ evaluations, the final version of the instrument for the pretest was constituted. It applies the instrument in a given sample of the population and aims to detect errors, and confirms the clarity and understanding of the items by the population (22). The target population of the instrument refers to caregivers of family members with Chronic Disease, who, in the case of this research, referred to people with CKD on hemodialysis. In this context, the pre-test phase of the instrument was developed with 14 family caregivers of people on hemodialysis, which enabled the improvement of the measuring instrument.

The sociodemographic profile and aspects related to the care of the pre-test caregivers consisted of women, mostly married, and who had not finished elementary school, with a mean age of 49.92 years. In addition, it was found that 57.14 % of the caregivers took care of their parents (25). It is noteworthy that, with regard to third-party help for the caregiver, 78.58 % reported receiving help from someone else in care. Regarding the patient’s financial situation, 64.28 % said that the family member does not receive financial help in care.

Researchers described the experience of caregivers of peritoneal dialysis patients who participated in a program focusing on care ability. The research included a sample of 277 family caregivers, most of whom were female, married and with a similar average age to the present study. The results highlighted seven aspects that the program helped to strengthen: new knowledge; interaction with other caregivers; support; rest; well-being; opportunity to improve care; and, finally, a new perspective for caregivers. The authors concluded that the program broadened caregivers’ experiences (25).

Another study conducted with eight family caregivers of patients with CKD undergoing hemodialysis, aiming to investigate the perception of family members regarding the care provided, found that most caregivers were women (62.50 %), with a mean age of 47 years old (26). In the study, the caregivers showed that they learnt some skills concerning the complications that occurred after the treatment session, who constantly receive guidance from the physician on duty, as well as the nurse. In addition, caregivers realize how important it is to talk about the family member’s clinical condition and report that they are feeling the burden of responsibility that leads to overload. The authors concluded that caregivers easily adapt to this new life condition, overcoming all limitations and increasing their specific knowledge.

Researchers compared the care ability and overload of caregivers who look after patients with CKD on peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis who were attended at the Specialized Institution in Ciudad de Cúcuta (Colombia) in 2015 and 2016. It should be mentioned that 25 caregivers of people on peritoneal dialysis and 43 caregivers of people on hemodialysis took part in the study. Among the results, it was observed that most participants were women, who had little education and were married. The results showed that the care skills were similar in the groups, however the “relationship” and “change in routine” dimensions were better in the hemodialysis group, while the caregiver commitment was similar in the groups, with worse overload levels. In addition, caregivers of family members on hemodialysis had greater care ability and a lower overload than caregivers of people on peritoneal dialysis (27).

In this context, it can be seen that, in general, the sociodemographic profile and aspects related to the care of the participants in the pretest of this study resembled the aforementioned research, also developed with caregivers of family members with CKD.

The main purpose of the pre-test of the instrument was to identify problems in understanding the terms used in the questions by the participants. Therefore, when evaluating the instrument items, the participants were asked about the clarity of each item and, if the answer was negative, the respondent suggested changes to improve understanding. This phase aims to investigate the presence of difficulties in understanding how the questions, the content and the answer options were expressed (28).

The clarity/comprehension/relevance of the statements was also verified through the Disabkids adapted general clarity questionnaire (19) for the research, which allowed the 14 participants to evaluate the relevance of the Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases in Brazil, in the case of CKD on hemodialysis. Thus, the semantic validation of the instrument occurred; each of the questions was evaluated according to its meaning, relevance and understanding.

A group of researchers carried out the translation and adaptation of the Disabkids - Cystic Fibrosis Module, Brazilian version - questionnaire, and the pre-test phase was done by 12 people, who also answered the above questionnaire for semantic validation of the questionnaire. The authors concluded that this clarity instrument was important due to the participants’ assessment of the questionnaire and, as in the present study, there were no suggested changes (29).

The patients in this study rated the Scale as clear and comprehensible, as well as being relevant to evaluate the experiences of family caregivers of people with CKD undergoing hemodialysis, corroborating the findings of other researchers who reported that the pretest step is a proof technique, because it can ascertain the understanding of the instrument by the population, as they mention that it is a proof technique, which makes it possible to ascertain the understanding of the instrument by the population sample (22).

It is worth reiterating that there was still a reanalysis of the content of the items in relation to the verb tense, although the caregivers had not suggested alterations, but during the pretest, the interviewer realized that the standardization of the verb tense for the present tense would make it easier for the participants to understand; as a result, this last adaptation was chosen, reaching the final adapted version of the scale. Situations such as these (item reanalysis) are predicted during the translation and cultural adaptation process of measuring instruments, as can be observed in the investigation by Roediger et al. (30), who adapted the Determine your nutritional health® method to Portuguese with elderly people at home and advocated using a single verb tense, as each question referred to different events, not at a single moment. (30).

Study limitations include the pre-test sample size. Another limiting aspect refers to the respondents being linked to a single RRTU, which prevents gaining more knowledge about care in different cultures and regions of Brazil. Finally, there is a lack of articles on the subject in the population with CKD.

Conclusions

Based on the proposed objective and the results obtained, it can be concluded that the Scale to Measure Care Ability of Family Caregivers of People with Chronic Diseases is duly translated and culturally adapted to Brazil.

After finishing the analysis step of the psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the instrument, we intend to make it available for care and investigative use regarding the caregivers’ care ability of family members with Chronic Disease by multidisciplinary teams, which would enable the improvement of care and scientific evidence on the subject.

Regarding the use of this scale, professionals will be equipped to propose preventive and educational measures in order to provide the patient with Chronic Disease with quality care that favors adherence to treatment.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

1. Ribeiro F, Marques B, Botelho MR, Marcon SS, Lenzi JS. Coping strategies used by family members of individuals Receiving hemodialysis. Texto contexto 2014;23(4):915-24. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072014002220011

2. Gonzalez ME, Maria M, C, Gelehrter R, Lopes C. Convivendo com a doença renal: entre ditos e não ditos. 2018 [acesso 19 jan. 2019];108-14. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328307572_Convivendo_com_a_doenca_renal_entre_ditos_e_nao_ditos

3. Holanda PK, Abreu IS. The chronic renal patient and the adherence to hemodialysis treatment. Rev Enferm UFPE. 2014;8(3):600-5. Available from: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/revistaenfermagem/article/view/9715

4. Fernandes CS, Angelo M. Family caregivers: what do they need: an integrative review. Rev Esc Enferm USP [Internet]. 2016;50(4):675-82. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420160000500019

5. Costa FG, Coutinho M da PDL. Síndrome depressiva: um estudo com pacientes e familiares no contexto da doença renal crônica. Estud Interdiscip em Psicol [Internet]. 2016;7(1):38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5433/2236-6407.2016v7n1p38

6. Faleiros AH, Santos CA, Martins CR, Roth AHR. Os Desafios do cuidar: revisão bibliográfica, Sobrecargas e satisfações do cuidador de idosos. Janus [Internet]. 2018 [acesso 5 jul. 2018];12(6):59-68. Disponível em: http://fatea.br/seer/index.php/janus/article/viewFile/1793/1324

7. Aparecida WAG de, Borini FM, Souza ECP. Competências Comportamentais dos Profissionais de Secretariado: o impacto da atuação internacional da empresa. Revista de Gestão e Secretariado. 2018;9(1):1-17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7769/gesec.v9i1.632

8. Farah BF, Dutra HS, Sanhudo NF, Costa LM. Percepção de enfermeiros supervisores sobre liderança na atenção primária. Rev Cuid. 2017;8(2):1638-55. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.15649/cuidarte.v8i2.398

9. Mercado MV, Ortiz LB. Confiabilidad del instrumento “habilidad de cuidado de cuidadores de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas”. Av en Enfermería. 2013;31(2):12-20. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/avenferm/article/view/42686/60809

10. Barrera L. Construcción validación de instrumento para medir la habilidad de cuidado de cuidadores familiares de personas con enfermedad crónica. Documento archivo Grupo Cuidado al Paciente crónico. Bogotá: Facultad de Enfermería, Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2008.

11. Díaz B, Yamile L. Confiabilidad y validez de constructo del instrumento “habilidad de cuidado de cuidadores familiares de personas que viven una situación de enfermedad crónica” [tesis]. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2010. Disponible en: http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/3806/

12. Hernández P, Nieves B. Confiabilidad del instrumento para medir “habilidad de cuidado de cuidadores familiares de personas con enfermedad crónica” en cuidadores de personas mayores de la localidad de Usaquén. Bogotá. Distrito Capital [tesis]. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2011. Disponible en: http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/3925/

13. Mercado MV. Confiabilidad del instrumento “habilidad de cuidado de los cuidadores familiares de personas con enfermedad crónica” [tesis]. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2011. Disponible en: http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/4122/

14. Blanco-Sánchez JP. Validación de una escala para medir la habilidad de cuidado de cuidadores [tesis]. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2013. Disponible en: http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/43068/

15. Schmidt Piovesan Rosanelli CL, da Silva LM, de Rivero Gutierrez MG. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Caring Ability Inventory to Portuguese. Acta Paul Enferm. 2016;29(3):347-54. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-0194201600048

16. Silva FPDS. Avaliação dos hábitos de vida segundo a Assessment of Life Habits (LIFE-H): adaptação cultural e valores normativos para crianças brasileiras [tese]. São Carlos: Universidade Federal de São Carlos; 2015. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufscar.br/handle/ufscar/7637

17. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F FM. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-91. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

18. Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35(6):382-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198611000-00017

19. Deon KC, dos Santos DM de SS, Reis RA, Fegadolli C, Bullinger M, dos Santos CB. Translation and cultural adaptation of the Brazilian version of DISABKIDS®* Atopic Dermatitis Module (ADM). Rev da Esc Enferm. 2011;45(2):441-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342011000200021

20. Jensen R, Cruz D de ALM da, Tesoro MG, Lopes MHB de M. Translation and cultural adaptation for Brazil of the Developing Nurses’ Thinking model. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2014;22(2):197-203. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.3232.2402

21. Rosanelli CLSP. Adaptação transcultural e validação do caring ability inventory. Univ Fed São Paulo. 2014. Available at: http://repositorio.unifesp.br/handle/11600/47983

22. Guillemin F, Bombardier C BD. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(12):1417-32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N

23. Coluci MZO, Alexandre NMC, Milani D. Construção de instrumentos de medida na área da saúde. Cien Saude Colet [Internet]. 2015;20(3):925-36. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015203.04332013

24. Nora CRD, Zoboli E, Vieira MM. Validation by experts: importance in translation and adaptation of instruments. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2017;38(3):1-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2017.03.64851

25. León DL, Calderón LR, Moreno SC, Cuenca I, Lorena Chaparro Díaz. Cuidadores de pacientes en diálisis peritoneal: experiencia de participar en un programa de habilidad de cuidado. Enferm Nefrol. 2015;18 (3):189-95. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S2254-28842015000300007

26. Rodrigues de Lima L, Flôres Cosentino S, Marinês dos Santos A, Strapazzon M, Cembranel Lorenzoni AM. Family perceptions of care with patients in renal dialysis. J Nurs UFPE on line/Rev enferm UFPE on line. 2017;11(7):2704-10. Available from: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/revistaenfermagem/article/view/23443/

27. Pérez CLP. Habilidad de cuidado y sobrecarga en cuidadores de personas en terapia de hemodialisis y diálisis peritoneal [tesis]. Bucaramanga: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2017. Disponible en: http://bdigital.unal.edu.co/63639/1/HABILIDAD%20DE%20CUIDADO%20Y%20SOBRECARGA%20EN%20CUIDADORES%20DE%20PERSONAS%20EN%20TERAPIA%20DE%20HEMODIALISIS%20Y%20DI%C3%81LISIS%20PERITONEAL.pdf

28. Tagliaferro M, Gonçalves A, Bergmann M, Sobral O, Graça M. Share request full-text assessment of metal exposure (uranium and copper) by the response of a set of integrated biomarkers in a stream shredder. Ecol Indic. 2018;95(parte 2):991-1000. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.10.065

29. Santos DMSS, Deon KC, Fegadolli C, Reis RA, Torres LAGMM, Bullinger M et al. Cultural adaptation and initial psychometric properties of the Disabkidstm — cystic fibrosis module — Brazilian version. Rev da Esc Enferm. 2013;47(6):1311-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420130000600009

30. Roediger M de A, Marucci M de FN, Latorre M do RD de O, Hearst N, Oliveira C de, Duarte YA de O et al. Adaptação transcultural para o idioma português do método de triagem nutricional Determine your nutritional health® para idosos domiciliados. Cien Saude Colet [Internet]. 2017;22(2):509-18. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232017222.00542016