Article

Gisele Weissheimer1

Julia Mazul Santana2

Victória Beatriz Trevisan Nóbrega Martins Ruthes3

Verônica de Azevedo Mazza4

* This article was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Ministry of Technology, Science and Information, with funds obtained by the Universal Project, approved by MCTI/CNPq 1/2016. It is also derived from the first developmental stage of the doctoral thesis entitled “Informational support for the families of children with autism: Content validation”, defended at the Federal University of Paraná, Brazil.

* El artículo fue auspiciado por el Consejo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico, Ministerio de la Tecnología, Ciencia e Información de Brasil, con recursos del Proyecto Universal, aprobado por la convocatoria MCTI/CNPq 1/2016. Además, se deriva de la primera etapa de desarrollo de la tesis doctoral titulada “Soporte informacional a las familias de niños con autismo: validación de contenido”, presentada en la Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brasil.

* Este artigo foi financiado pelo Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Ministério da Tecnologia, Ciência e Informação, com recursos obtidos pelo Projeto Universal, aprovado pela chamada MCTI/CNPq 1/2016. Também é derivado da primeira etapa de desenvolvimento da tese de doutorado intitulada “Suporte informacional às famílias de crianças com autismo: validação de conteúdo”, defendida na Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brasil.

1 ![]() 0000-0002-3054-3642.

Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil. gisele.weissheimer@hc.ufpr.br

0000-0002-3054-3642.

Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil. gisele.weissheimer@hc.ufpr.br

2 ![]() 0000-0002-3419-8727.

Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil.

0000-0002-3419-8727.

Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil.

3 ![]() 0000-0003-1525-580X.

Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil.

0000-0003-1525-580X.

Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil.

4 ![]() 0000-0002-1264-7149.

Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil.

0000-0002-1264-7149.

Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil.

Received: 23/03/2020

Sent to peers: 05/04/2020

Accepted by peers: 20/05/2020

Approved: 09/06/2020

Theme of the journal: Chronic Care.

Contribution to the subject: This research contributes to the areas of nursing and health by offering theoretical support on the relevant information for the families of children with autism spectrum disorder. From this, the professionals can develop or improve formal information support programs.

Para citar este artículo / To reference this article / Para citar este artigo: Weissheimer G, Santana JM, Ruthes VBTNM, Mazza VA. Necessary Information for the Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Integrative Review. Aquichan. 2020;20(2):e2028. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2020.20.2.8

|

Abstract Objective: To identify the available evidence on the necessary information for the

families of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Keywords (Source DeCS): Autism Spectrum Disorder; access to information; family; child; social support. |

Resumen Objetivo: identificar

las evidencias disponibles acerca de las informaciones necesarias para las

familias de niños con desorden del espectro autista (DEA). PALABRAS CLAVE (Fuente DeCS): Desorden del espectro autista; acceso a la información; familia; niño; apoyo social. |

Resumo Objetivo: identificar as

evidências disponíveis sobre as informações necessárias às famílias de criança

com transtorno do espectro autista (TEA). PALAVRAS-CHAVE (Fonte DeCS): Transtorno do espectro autista; acesso à informação; família; criança; apoio social. |

Introduction

Estimates show that 1 in 59 children has Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). These are data from the Monitoring Network in the United States, between 2000 and 2014 (1). In Brazil, there are few epidemiological studies on the prevalence of ASD and discrepancies among some studies (2-4).

ASD is a human neuro-developmental disorder characterized by impaired social interaction (verbal and non-verbal), communication, and restricted and/or repetitive behavior patterns (5). Developmental alterations are perceived by the families based on some signs, such as delayed speech or language, stereotyped behaviors, and the child’s lack of interaction with other individuals (6).

The families are faced with something unknown and unexpected (7). Many of them face many obstacles and challenges in the health services to seek a child diagnosis (6), and they also need different types of support to take care of the child. Several studies show(8, 9) the need for the families to obtain information about available resources(8) and professionals, and express difficulties in accessing information and assistance resources(9).

The provision of information is part of health care and aims to improve the family’s knowledge and skills to influence attitudes and behaviors aiming at maintaining or improving the health of the family members(10). It is an important resource to empower them for care, as well as to assist them in the discussion with the professionals about the conduct to be taken regarding the child treatment and their rights, among others (11, 12).

Thus, the importance is evidenced of providing information to the families, as well as guidance on the use of resources available in different platforms accessible to the community, which are increasingly part of people’s daily lives.

To promote informational support for the families, it becomes relevant to identify the evidence on their information needs to develop strategies to help them. Thus, the aim is to identify what information is necessary for the families of children with ASD.

This study contributes to the Nursing course as it offers a theoretical basis to help the professionals in the area to provide information in an appropriate way in the care process, managing the family’s expectations about the usefulness of the information available from different sources.

Method

This is an integrative literature review, whose method allows for the synthesis, in a systematic and orderly way, of several published research studies on a topic, with the purpose of generating new results, deepening knowledge, and identifying possible gaps to be investigated about this topic (13). The study followed the six stages of Ganong’s methodology (14), presented below.

1). Definition of the research question: What evidence is available on the information needed by the families of children with ASD? For this, the researchers used an adaptation from the PICO strategy (P – Population; I – Intervention; C – Comparator; O – Outcomes) to PIC, where: P – Population; I – Phenomenon of Interest; C – Context. Thus, P – Families of children with ASD; I – Need for information; C – Context of daily family life.

2). Establishment of the inclusion/exclusion or sample selection criteria: studies that addressed family members of children with ASD; that specified the necessary information for these family members to help them in the daily care of the child; published between January 2014 and February 2020; qualitative and quantitative research studies available in full and free of charge in Spanish, English and Portuguese, in the Scopus, PubMed (US National Library of Medicine National Institutes Database Search of Health), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Science, Eric (Education Resources Information Center), and PsycINFO (American Psychological Association) databases.

The period of publication of the articles was defined to encompass more recent publications, from the last six years. Table 1 illustrates the search strategies carried out in the databases. Different databases were selected as the topic covers different areas of knowledge, such as Education, Psychology, Nursing, and multidisciplinary health sectors.

Table 1. Search strategy in the databases

Scopus |

TITLE-ABS-KEY (autism AND child AND family AND information) AND (LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR, 2020 Feb) (LIMIT-TO ( PUBYEAR, 2019) (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2018) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2017) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2016) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2015) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2014) ) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”) OR LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “Portuguese”) OR LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “Spanish”)) AND (EXCLUDE (EXACTKEYWORD, “Adult”) OR EXCLUDE (EXACTKEYWORD, “Adolescent”) OR EXCLUDE (EXACTKEYWORD, “Young Adult”) OR EXCLUDE (EXACTKEYWORD, “Middle Aged”)) |

PubMed |

Autism AND family AND child AND information |

CINAHL |

AB autism spectrum disorders AND children AND family AND information |

Web of Science |

TOPIC: (Autism) AND TOPIC: (family) AND TOPIC: (children) AND TOPIC: (information) AND DOCUMENT TYPES: (Article) AND YEAR PUBLISHED: (2014-2020) NOT TOPIC: (adolescent) NOT TOPIC:(adult) NOT TOPIC: (old) |

Eric |

Autism AND family NOT adolescent |

PsycINFO |

Any Field: autism spectrum disorders OR Keywords: autism AND Any Field: family experience OR Keywords: family AND Abstract: information AND Document Type: Journal Article AND Population Group: Human AND Age Group: Childhood (birth-12 yrs) AND APA Full-Text Only AND Year: 2014 To 2020 |

Source: Research data, own elaboration.

The exclusion criteria included repeated publications in the databases, dissertations, theses, review articles, conference reports, congresses, book chapters, books, letters, errata, experience reports, and editorials. Review articles were excluded because the aim was to include primary/empirical research studies. Reviews are characterized as secondary research studies.

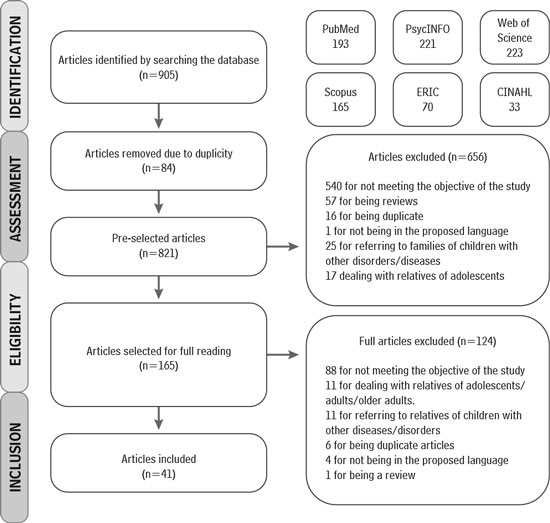

After identifying the studies in the databases and considering the eligibility criteria, two independent reviewers read the titles and abstracts simultaneously, in order to select the studies for the review. In cases of lack of consensus for the inclusion or not of the study, a third reviewer was consulted, which was not necessary; then, the pre-selected studies were read in full to define their inclusion or exclusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the process for the identification, selection and inclusion of the studies based on the PRISMA recommendation (15)

Source: Research data, own elaboration.

3) Data collection/extraction: The included studies were organized using an instrument predefined by the researchers with identification information such as the database, title, authors, journal, year of publication, language, country of the study, objective of the study, and methodological approach.

4) Analysis: The extracted data were classified according to thematic similarity and organized into categories. In this analysis, the methodology proposed by Bardin (16) (2010) was used, consisting of analysis organization, floating reading of publications, coding, and thematic categorization (16). The thematic analysis and categorization were performed by the researchers. They also organized and prepared data for analysis, reading, and coding into text segments, text groupings in categories according to the similarity between the data found.

5) Interpretation and discussion of the results.

6) Presentation of the integrative review.

Result

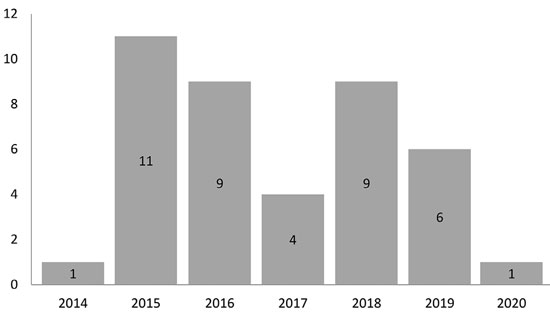

The sample consisted of 41 studies, and their characterization is shown in Table 2. As regards the year of publication of the articles: 1 (2.4 %) in 2014; 11 (26.2 %) in 2015; 9 (21.95 %) in 2016; 4 (9.75 %) in 2017; 9 (21.95 %) in 2018; 6 (14.6 %) in 2019 and 1 (2.4 %) in 2020, as shown in Figure 2. All were conducted in foreign countries: 17 (41.52 %) in the United States; 5 (12.2 %) in Australia; 3 (7.3 %) in Canada and Sweden; 2 (4.9 %) in China, the United Kingdom and Ireland; in Croatia, Spain, France, Greece, Italy, Russia and Turkey, 1 (2.4 %) article was published. Regarding the methodology, 23 (56.1 %) articles used a qualitative approach, 11 (26.8 %) used a quantitative approach, and 7 (17.1 %) used a quantitative and qualitative approach. With regard to the language of the studies, 40 (97.6 %) are in English and 1 (2.4 %) in Spanish.

Table 2. Characterization of the selected articles (2020)

Study Identification |

Country/ Journal/ Database |

Objective |

Blauth, 2017 (17) |

United Kingdom/Health Psychology Report/Web of Science |

To report the counseling approach to parents of children with ASD, using video feedback of the music therapy sessions with the children. |

Carlsson, Miniscalco, Kadesjö and Laakso, 2016 (18) |

Sweden/International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders/PubMed |

To foster the understanding of the experience lived by the parents in the neuropsychiatric diagnosis process, that is, the period from the initial screening at 2.5 years old to the 2-year follow-up of the ASD diagnosis. |

Chiu et al., 2014 (19) |

China/Journal of the Formosan Medical Association/Web of Science |

To describe the current practice of counseling on the diagnosis of ASD; to evaluate the mother’s satisfaction with the informed counseling on the diagnosis; to identify the factors related to the mother’s satisfaction; presenting the ideal counseling for the diagnosis expected by the mothers. |

Curtiss and Ebata, 2019 (20) |

United States/Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders/Eric |

To explore the nature of the family meals shared with children with ASD. |

Derguy, Michel, M’bailara, Roux and Bouvard, 2015 (21) |

France/Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability/Scopus |

To know the needs of parents of children with ASD. |

Dinora, Bogenschutz and Lynch, 2017 (22) |

United Kingdom/Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation/Web of Science |

To identify which factors families prioritize as important when selecting treatments for their children with ASD, which people and materials influence their treatment decisions, and the level of importance that the parents attribute to the different types of influences. |

Dinora and Bogenschutz, 2018 (23) |

United Kingdom/Journal of Early Intervention/Scopus |

To identify which experiences, beliefs, and life values influenced both the parents’ decisions to have their children evaluated for ASD and their decisions for ASD treatment, and to explore how the external factors affected the assessment and treatment decisions for ASD. |

Edwards, Brebner, McCormack and MacDougall, 2018 (11) |

Australia/Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders/Scopus |

To explore how the parents of children with ASD made decisions about which intervention they accessed. |

Frame and Casey, 2019 (24) |

United States/Children and Youth Services Review, Elsevier/Web of Science |

To identify the reasons and potential influences that made parents select the treatment for their children with ASD. |

Frye, 2016 (25) |

United States/Journal of pediatric health care/PubMed |

To write about the experience of parents of children with ASD, using their own words, and to identify what resources are needed to help them become actively involved in their role as parents of a child with ASD. |

Gibson, Kaplan and Vardell, 2017 (26) |

United States/Journal of autism and developmental disorders/PubMed |

To examine the preferences of the information source for the parents of individuals with ASD in North Carolina. |

Grant, Rodger and Hoffmann, 2016 (27) |

Australia/Child: Care, Health and Development/PubMed |

To explore the parents’ decision-making processes and information preferences after their child is diagnosed with ASD. |

Hays and Butauski, 2018 (28) |

Australia/Western Journal of Communication/Scopus |

To explore with whom the parents shared particular details regarding their children’s ASD. |

Hennel et al., 2016 (29) |

Australia/Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health/Web of Science |

To compare the parents’ experiences and preferences about the information offered by the pediatricians in the diagnosis of children with ASD, and to identify the types and usefulness of the resources accessed by the families after the diagnosis. |

Hodgetts, Zwaigenbaum and Nicholas, 2015 (30) |

Canada/Autism/CINAHL |

To explore the general needs, the benefits, and the weaknesses of the services that served the families of children with ASD, and to identify the predictors of those needs. |

Huus, Olsson, Andersson, Granlund and Augustine, 2017 (31) |

Sweden/Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research/Scopus |

To investigate the family’s perception about the needs of parents of children with a diagnosed mild intellectual disability, autism, Asperger’s Syndrome, epilepsy, and cerebral palsy; to investigate the relationship between the parents’ perception of self-efficacy in their parental role and the collaboration with the professionals, as well as with their support needs. |

Kocabiyik and Fazlioğlu, 2018 (32) |

United States/Journal of Education and Training Studies/Eric |

To determine how children diagnosed with ASD shaped their parents’ lives, with details about their life stories. |

Lajonchere et al., 2016 (33) |

United States/Journal of autism and developmental disorders/Web of Science |

To develop and perform a field test with an educational product called “Science Briefs”, which was designed to improve parents’ access to information in published biomedical research studies on ASD. |

Li et al., 2016 (34) |

United States/Patient Education and Counseling/Web of Science |

To examine the needs for information on the genetic test for ASD among parents of affected children. |

Liu e Fisher, 2017 (35) |

Australia/Australian Social Work/Web of Science |

To explore family experiences in the use of the support services for children with disabilities in order to understand how migration and their cultural expectations about disability and services affected the way they used the services. |

Lopes, Magaña, Xu and Guzman, 2018 (36) |

United States/Journal of Rehabilitation/Scopus |

To explore and understand the parents’ reaction to the diagnosis of ASD so as to support them. |

Mcintyre and Brown, 2016 (12) |

United States/Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability/Scopus |

To examine the use and usefulness of social support for the mothers of children with ASD. |

Mereoiu, Bland, Dobbins and Niemeyer, 2015 (37) |

United States/Early Childhood Research & Practice/Eric |

To explore the opinions of parents of preschool children with ASD in child care programs. |

Molteni and Maggiolini, 2015 (38) |

Italy/Journal of Child and Family Studies/Scopus |

To monitor the needs of the families of children with ASD, and to identify possible operational proposals in order to improve the quality of the territorial services. |

Moro, Jenaro and Solano, 2015 (39) |

Spain/Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca/Scopus |

To know the communication process of the diagnosis and the information received; to assess the perception of the relationship between families and professionals; to understand the support and obstacles perceived by the parents regarding their children’s ASD. |

Ntre et al., 2018 (40) |

Greece/International Journal of Caring Sciences/CINAHL |

To investigate the general concerns and the support and information needs of Greek mothers of children with ASD, their health problems, and the family’s financial burden. |

Pearson, Traficante, Denny, Malone and Codd, 2019 (41) |

United States/Journal of Autism and Development Disorders/Scopus |

To meet the needs of children with ASD and their families, and to offer parents opportunities to learn about ASD services available in their communities. |

Pejovic-Milovancevic, 2018 (42) |

Siberia/Psychiatria Danubina/Scopus |

To explore the support, challenges, and needs among the families affected by ASD in Serbia, and to define the family’s general satisfaction with the support offered by the systems. |

Pickard and Ingersoll, 2015 (43) |

United States/Autism/PubMed |

To examine the service needs perceived by the parents and the barriers to using the service. |

Pickard, Rowless and Ingersoll, 2019 (44) |

United States/Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders/Eric |

To assess the impact of the adaptations to a parent-mediated and evidence-based intervention. |

Preece et al., 2016 (45) |

Croatia/European Journal of Special Needs Education/Web of Science |

To identify the parent’s attitudes and opinions in relation to receiving training for parents (time, duration of the sessions, possible barriers) and the training content. |

Prendeville and Kinsella, 2019 (46) |

Ireland/Journal of Autism And Development Disorders/Web of Science |

To explore how grandparents support children with ASD and their parents by using a family systems perspective. |

Rivard, Lépine, Mercier and Morin, 2015 (47) |

Canada/Journal of Child and Family Studies/Scopus |

To analyze how the parents of children with ASD perceived the determinants of the quality of the services provided in the context of a public service network. |

Rivard, Millau, Magnan, Mello and Boulé, 2019 (48) |

Canada/Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities/Web of Science |

To document obstacles faced by immigrant families in obtaining a diagnosis of ASD for their child; to document the factors that facilitated access to the diagnosis; to identify predominant attitudes in relation to ASD in the participants’ culture of origin; and to record the advice that the participants would give to other immigrant families on their own path to obtain a diagnosis. |

Roffeei, Abdullah and Basar, 2015 (49) |

United Kingdom/International Journal of Medical Informatics/Scopus |

To explore the points of view of the parents and of the interested parties (pediatrics, psychiatry, psychology, mental health services, research, and national charities for ASD) regarding their information needs, current information modalities, and perceived barriers and complexities of the information. |

Ryan and Quinlan, 2018 (50) |

Ireland/Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities/Web of Science |

To explore the parents’ perceptions of the communication and collaboration with the health team and of education in the context of a reconfiguration of disability services. |

Tait, Hu, Sweller and Wang, 2016 (51) |

China/Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders/PubMed |

To describe the family’s understanding of their own quality of life and the diagnostic services they used. |

Tekinarslan, 2018 (52) |

Turkey/Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities/Eric |

To explore the experiences of Turkish mothers whose children were diagnosed with ASD regarding the emotions they felt and the challenges they encountered before and after the diagnosis. |

Wallace, 2016 (53) |

United States/The Qualitative Report/Scopus |

To determine the impact of camping experiences on families of children with ASD. |

Zajicek-Farber, Lotrecchiano, Long and Farber, 2015 (54) |

United States/ Maternal and child health journal/Web of Science |

To explore the families’ perception of the experience with family-centered care of children with neuro-developmental disabilities, received in medical services. |

Zakirova-Engstrand, Roll-Pettersson, Westling-Allodi and Hirvikoski 2020 (55) |

Sweden/Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders/Web of Science |

To report discoveries about the perceived needs of the grandparents of children with ASD in the Swedish cultural context. |

Source: Research data, own elaboration.

Figure 2. Number of selected articles per year of publication (2020)

Source: Research data, own elaboration.

From the thematic analysis of the data, two categories and respective subcategories emerged: “Need for information” and “information support sources of the families”, according to Figure 3.

Figure 3. Categories and subcategories

Source: Research data.

Need for information

It was verified that the parents needed information that would help them care for their children. This category was divided into four subcategories that express the content of the information required by the families: ASD, the child with ASD, rights of the child with ASD, and information sources.

In the “ASD” subcategory, in articles 19, 21, 23, 27, 31, 36, 37, 43, 45, 47, 55 and 56, it was observed that the parents considered important to receive information about ASD, such as the definition of the disorder, its cause, signs, and symptoms (19, 43, 50, 57), about specific diets (26), diagnostic tests and exams (27, 41), genetic tests and the probability of having a second child with ASD, about the meaning of diagnosis and prognosis (31), treatment options (26, 43, 47), alternative child care therapies (47), and possibility of finding a cure (35, 38).

In the “child with ASD” subcategory, information needs were identified on how to manage and understand the child’s behavior and future. According to studies 22, 23, 26, 32, 38, 43 and 55, the parents need knowledge to understand the behaviors of children with ASD and to deal with them, to manage aggressive, self-injurious behaviors, tantrums, and stereotypes. In addition, they would like to know about the development of social and sensory skills, how to manage the child’s limitations, how to manage their nutrition (22), and how to assist in their social integration with their own family and other individuals in society.

The families wanted instructions that would help them to communicate with the child, create daily routines of rest, sleep, self-care, and leisure (47), advice that would guide them on how to play with the child, promote their independence, how to manage sexuality, and the beginning of adolescence (24, 47, 55).

Articles 32, 33, 41, 42 and 52 disclosed the need for information that addressed each stage of child development and its demands. This involves from the child’s ability to speak, communicate, socialize, and adapt in society up to the stage of growth and physical and sexual development; in addition, it covered performance in the educational setting, the possibility of studying in regular schools, entering the labor market, gaining independence, and being happy.

In relation to the “rights of the child with ASD” subcategory, the family members sought clarification about rights, policies, legislation (47), financial support for people with disabilities, and governmental resources for early intervention (31). Instructions were sought to help them explain the disorder to others and raise awareness about ASD (47, 50, 55).

Studies 20, 21, 23, 25, 29, 31-33, 42, 43, 52, 53, 54 and 55 showed that the families needed information about services available for their children and qualified health professionals to make the diagnosis, offer treatment/therapy and family counseling. Accordingly, there was a need for information on health plans that covered children with ASD, as well as on where to seek support, intervention, and educational resources to stimulate child development. In addition, they expressed the need to learn to better communicate with teachers and other professionals in relation to the child with ASD and to obtain family counseling for parents and grandparents (57).

Regarding the “information sources” subcategory (29, 31), the families would like advice on how to seek or find support groups and organizations for parents of children with ASD. In articles 28, 29, 31 and 55, a need was verified for indications to participate in seminars/meetings, events focused on ASD, books and websites for parents.

Information support sources accessed by the families

In this category, the information sources used were classified into the following subcategories: formal, informal, and Internet/other resources.

In the “formal sources” subcategory, it was verified that the parents obtained information from different professionals; reported the type of information; indicated positive aspects in receiving reports; identified limitations of professionals and institutions on the information support, and pointed out aspects that hindered their participation in events of an informational nature. The parents sought information from professionals in several categories, such as in relation to the health area, like general practitioners (29, 30, 44), primary care physicians (24, 44), specialists in pediatrics and neurology (25), speech therapists, psychologists, and occupational therapists. Likewise, they received information from professionals in the education area, such as teachers from child education centers and schools (25, 27).

The positive aspects of the health professionals during the receipt of information in the diagnosis period were the following: positive attitude (21); they were sensitive, realistic, and careful in the way they communicated (41); the diagnosis was clear (25, 41); they offered emotional support and encouraged the parents to make questions (21, 31, 40); they had adequate time to discuss the diagnosis (31); they listened and reassured the parents(40); the parents received information about the rights of the child/family; had the opportunity to check their own understanding of the information received(55); were informed about the treatment (21,25), specialized centers and programs such as Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Picture Exchange Communication System, Treatment and Education of Autistic and Communication Handicapped Children, speech, psychomotor, and behavioral therapy (38). The parents participated in a training program that taught them to play with the child, improve communication, and deal with the child’s behavior (46).

In turn, negative aspects were observed when communicating the diagnosis: lack of empathy (52); little sensitivity (41); failure to meet the counseling needs (41); negative advice; pessimistic (21, 41) and distressing (31) attitudes; little time for counseling and insufficient information (19, 25, 55).

According to the families, the guidelines were not clear; the physicians were not sure of the diagnosis of child ASD (40), and the families did not understand the disorder (25, 38, 41, 53), the etiology, prognosis, clinical manifestations of ASD (16), the genetic test (12), the governmental subsidies, the health care provided, and the educational resources (21).

The families did not obtain information regarding their concerns about: the future (53), the child’s behavior (41, 53), the development and evolution of ASD (41), where to seek support (43), the child’s sensory needs (11), personalized interventions and therapies, the prognosis, and how to explain the diagnosis to the school professionals (31). In addition, they did not know where to look for institutions to assist and guide them (41).

The families pointed out some professional limitations during the process of providing information, namely: different levels of knowledge about ASD (25, 50, 52); contradictory information among the professionals (53); the family members did not understand the forwarding and sharing of information among the multi-professional team (50, 52); the professionals were unaware of services that provided specialized care to children with ASD (50). In addition, the families did not understand why the professionals did not listen to their concerns about the changes they perceived in the child’s development (25).

Regarding the institutional limitations, in a study conducted in Spain the absence of specialist professionals (41) was verified; and, in a research conducted in the United States, the overload of neurologists, which interfered with the provision of more care for the families after the diagnosis (25). Additionally, in a research study carried out in China, it was identified that the opening hours and days of the places intended to provide information to parents were limited, since they were open during business hours in general, and closed on weekends and holidays, making it impossible for family members who also work during office hours to use them. The lack of an information center offering online or telephone service 24 hours a day that could be accessed by families (53) was mentioned.

The family members indicated limitations in the participation in training for parents due to the fact that they were held in other cities and due to the coincidence with their schedule of care for the child or their working hours. In addition, there were no alternative training schedules, for example, during weekends or at night (47). In addition, many families reported lack of time and motivation to participate in training sessions due to the physical exhaustion caused by the child’s care routine (51).

In relation to the “informal sources” subcategory, it was verified that the parents obtained information from other parents of children with ASD and from friends in similar conditions (11, 20, 22, 24, 31, 35, 55). The families shared information with spouses and other members, such as the child’s siblings, uncles, cousins, and grandparents (12, 30, 34, 48), other members of the personal network, such as neighbors or friends (32, 33, 37, 38), and support groups or associations (11, 28-30, 52). Grandparents have an important role in sharing information and supporting parents of children with ASD (48).

In the “Internet and other resources” subcategory, the following was observed: use of such resources, the information sought, and the difficulties and limitations for using the Internet and books. It was verified that the family members participated in workshops, read books and pamphlets, and watched videos, which were mentioned as means to obtain information (24, 27, 28, 34, 36, 44, 54). They used the Internet (31) and blogs (26) to obtain knowledge about the rights of the child (37), the possible causes of ASD, the various treatments, treatments with few studies that prove their effectiveness (35), and the genetic test for children with ASD (12).

Regarding the use of information on the Internet, many parents mentioned some difficulties, such as the massive amount of information (12, 24, 26, 51), confusing information with many terms (ASD, autistic, Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Asperger, etc.) (53); difficulties in discerning reliable information from online myths (25); websites intending to sell products (51); and lack of reliable information (31, 51).

Other limitations to access the Internet were the educational and/or socioeconomic disadvantages that make access to a computer impossible, not knowing how to use it or not understanding the technical language with which information is availed, and the inability to seek reliable information (35, 51).

With regard to the use of books, the following limitations were described: the parents felt overloaded due to the amount of information provided; technical language and parents’ fatigue to read due to the care routine (51). The identity of the individuals with ASD was inadequately defined; thus, the parents were not comfortable reading such books (51). Another concern raised was the families’ vulnerability to the different information sources available since, after the diagnosis, it is the period when parents need information the most and thus are susceptible to inadequate information (51).

Discussion

The families’ search for information begins with the perception that there is something different in the child’s development (20). After the diagnosis is confirmed, the families experience insecurity related to the lack of knowledge about ASD and the available treatments; the difficulty of dealing with the child’s behavior; the need to make decisions about treatments they do not know (24, 28, 29, 51, 56); and, in some cases, they have difficulty accessing resources, support, and information (39).

The family needs support from the family members, the professionals, and the community. However, in the studies reports were found of the lack of skills and welcoming of the professionals, mentioned by the families that need time for counseling, more information, to be heard, and to know how/where to look for resources (19, 20, 28, 41, 52, 53). Inadequate information can have a negative effect on the families, either by the inaccessibility of the information or by the limitations of the professionals in relation to the knowledge and management of ASD, effects described by the families in several studies (25, 52, 53). There are references to limitations in assisting the family members, such as the overload of the professionals – due to the demand for daily care – that end up limiting the time for counseling (25, 47).

The limited awareness on ASD by the community and the professionals is still a current aspect, which can have important consequences for the families (51). Among other aspects, the professionals not valuing the information reported by the families can lead to a delay in the diagnosis. This means wasted opportunities for early interventions that can make a difference in the child’s development, mainly related to brain plasticity in early life (57).

Limited information forces the families to face community stigmas, especially when the children with ASD present stereotypes, crises, or tantrums in public. The families are judged because people are unaware of the disorder and of how the person with ASD perceives the world and lives in society. This leads many parents to avoid going out and change their life routines in order to reduce unpleasant moments in the community (56).

Although various studies show that some families have difficulties in accessing information, others obtained positive advice from the health professionals and from the school(12), who were considered important sources of information before and after the diagnosis of ASD (31, 44), with the support received (44), and the guidelines to assist in the decisions regarding the treatments (25). Access to information is indispensable because it allows parents to feel safe and empowered to make decisions (29) regarding the treatment, the interventions, the services, and the future (55).

Many parents report that health professionals and formal institutions provide a feeling of trust and support to the family members who want honest information (27) regarding the child’s ASD and the indication of appropriate treatments (25). In addition to the professionals, many families use other means to obtain information about the disorder and to assist them in making decisions (39, 54), such as other parents of children with ASD, family members, friends, and neighbors. The parents value support groups as a source of guidance, as their participants experience the same situation and provide mutual support continuously (11, 25, 30, 31, 52).

The search for peers in the same situation refers to the fact that these families have a better understanding of what the others are feeling, unlike other people such as their own family, who are unable or do not have the knowledge to help them (54). Therefore, people who experience the same condition and who have already gone through several ways of seeking information and services become the hope of obtaining the ability to learn to deal with and face such situation (51, 55).

The families seek informational support by means of the social media, they interconnect through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, blogs, and podcasts, among others. Through this connection, they can provide a sense of belonging, mutual support, and a way to understand what is happening (58).

With the movement of the digital age and the increasingly frequent and easily accessible use of the Internet, it has become a source of search for information on health. The reasons for its use are the abundance of information, the easy access to this resource (28, 29) and the possibility to access the Internet according to the family’s time availability (29). Other resources, such as participation in workshops and seminars, are used in order to know the services available to assist children with ASD(37), as a type of training for parents(47) and of obtaining information to guide decision making on necessary interventions.

Despite the availability of information to the families, there is a concern about its reliability. The families’ emotional vulnerability to information sources is an important aspect to be discussed in contemporary society due to the increase in information available online (51).

The families are exposed to unreliable online content; additionally, there is emotional vulnerability regarding the search for a cure for ASD. This can make the family members trust unqualified contents that promise such a cure, which, so far, does not exist. The lack of evidence to prove the cause of and the cure for the disorder may justify the reason why parents seek so much information and alternative treatments. Although there are many levels of scientific credibility, an essential aspect for some parents is to understand reliable and unreliable content(53). Thus, the challenge for the professionals is to train the parents so that they can search for information in reliable databases.

Some families can be vulnerable to persuasive rhetorics of insecure information; however, not all families are influenced. With the movement of evidence-based practice, reliable studies are shown compared to those without validation. However, even evidence-based practices are vulnerable to commercialization (55).

There are some sources of support for the families, such as the provision of online content aimed at the parents (with a language proper for this population) and of educational content developed and made available on websites of scientifically recognized institutions, such as Autism Speaks (United States and partnerships with other countries), the Raising Children Network (Australia), and Sick Kids (Canada), among others.

With the use of technologies, contents can be shared during a webinar, which can be presented and later stored, so it can be watched by people who were unable to attend it live. A webinar can be used to present an educational program to a geographically broad group. For example, in rural areas, it can be difficult to organize a family education program because distance and time can prevent families from participating. However, as long as they have access to the Internet, they can participate in the program at their homes and have the opportunity to interact with the host and with other participants(58).

A study carried out in Canada showed that, in a health search conducted on YouTube, there were several videos developed by nurses and other health professionals with useful and reliable information for the families. Podcasts are another way to share popular and useful content. A podcast is an audio file that people can download to their cell phones and then listen to it while performing activities of daily living. Podcasts are usually short and people can subscribe to receive new podcasts directly, depending on the topic they want. Similar to these, there are also vodcasts (58).

Thus, a trend is perceived in the use of information freely accessible by the community. This creates a demand for professionals and managers to educate the community on how to access reliable information. In addition, it leads to the need to rethink the practice and to develop strategies that aim to minimize possible risks of accessing unsafe information that “uninstruct” the families and harm the health of children with ASD.

Conclusions

This research evidenced information patterns required by the families about ASD, the child’s behavior and rights, and the indication of information sources. With this data, the professionals can create or improve formal information support programs. Formal support involves programs and policies that are part of the assistance to families in different areas of health, social, and educational care.

The results provide a basis for managers in strategies for public policies aimed at this population in order to guarantee their rights. In addition, they also allow them to reflect on strategies to train the formal support sources so that they can manage the families’ needs.

In view of the various sources accessed by the family members and the reference to a large amount of information in these sources, there is a need to condense them into a usable format without families feeling overwhelmed. They could be condensed into a printed or online format in a specific place of access by the families. In addition, there were references to information of a questionable quality.

Considering the families’ vulnerability to accessing insecure information, there are challenges for the professional area in terms of availing and guiding secure and modeled information for the families given the trends in the digital age. In this context, the professionals are encouraged to teach the families to make a critical judgment in the selection of the sources and of the type of information accessed.

The limitations of this study included samples of children with conditions which are comorbid to ASD, since the information needs may be different for this group. Although studies involving adolescents and adults were excluded, many of those included had adolescents in their samples, thus some topics like sexuality emerged.

It is believed that the demand for information can be different in each stage of the life of children with ASD, as well as of their family members. Therefore, for future studies, it is suggested to investigate what these demands would be and their impact on those involved.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

1. Eds JB. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2018;67(6):1-23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1

2. Wuo AS. Education of people with autism spectrum disorders: State of knowledge in dissertations and theses in the Southern and Southeastern regions of Brazil (2008-2016). Saúde soc 2019;28(3):210-23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-12902019170783

3. Beck RG. Estimativa do número de casos de Transtorno do Espectro Autista no Sul do Brasil [dissertação]. Tubarão-SC: Universidade do Sul de Santa Catariana; 2017. Disponível em: https://riuni.unisul.br/handle/12345/3659

4. Organização Pan-Americana as Saúde — OPAS (Brasil). Folha informativa — Transtorno do espetro autista; 2017. Disponível em: https://www.paho.org/bra/index.php?Itemid=1098

5. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5: Manual diagnóstico e estatístico de transtornos mentais. Porto Alegre: Artmed Editora; 2014.

6. Ebert M, Lorenzini E, Silva EF da. Mothers of children with autistic disorder: perceptions and trajectories. Rev Gaucha Enferm. 2015;36(1):49-55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2015.01.43623

7. Zanatta EA, Menegazzo E, Guimarães AN, Ferraz L, Motta MGC. Families that live with child autism on a daily basis. RASD 2014;28(3):271-82. Disponível em: https://portalseer.ufba.br/index.php/enfermagem/article/view/10451/

8. Cappe É, Poirier N. Les besoins exprimés par les parents d’enfants ayant un TSA : une étude exploratoire franco-québécoise. Ann Med-Psychol. 2016;174(8):63943. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2015.06.003

9. Gilson CB, Bethune LK, Carter EW, Mcmillan ED. Informing and equipping parents of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017;55(5):347-60. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-55.5.347

10. Hall CM, Culler ED, Frank-Webb A. Online Dissemination of Resources and Services for Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs): A Systematic Review of Evidence. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;3(4):273-85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40489-016-0083-z

11. Edwards AG, Brebner CM, McCormack PF, MacDougall CJ. From “parent” to “expert”: How parents of children with autism spectrum disorder make decisions about which intervention approaches to access. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(6):2122-38. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3473-5

12. Mcintyre LL, Brown M. Examining the utilisation and usefulness of social support for mothers with young children with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil . 2016;43(1):93-101. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1262534

13. Ercole FF, Melo LS de, Alcoforado CLGC. Integrative review versus systematic review. REME rev. min. enferm. 2014;18(1):9-12. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5935/1415-2762.20140001

14. Ganong LH. Integrative reviews of nursing research. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10(1):1-11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770100103

15. Hutton B, Catalá-López F, Moher D. The PRISMA Extension Statement for Reporting of Systematic Reviews Incorporating Network Meta-analyses PRISMA-NMA. Med Clin. 2016. Available from: http://www.prisma-statement.org/Extensions/NetworkMetaAnalysis.aspx

16. Bardin, L. Análise de conteúdo. 4. ed. Lisboa: Edições70; 2010.

17. Blauth LK. Improving mental health in families with autistic children: Benefits of using video feedback in parent counselling sessions offered alongside music therapy. Health Psychol. 2017;5(2):138-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2017.63558

18. Carlsson E, Miniscalco C, Kadesjö B, Laakso K. Negotiating knowledge: Parents’ experience of the neuropsychiatric diagnostic process for children with autism. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2016;51(3):328-38. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12210

19. Chiu Y-N, Chou M-C, Lee J-C, Wong C-C, Chou W-J, Wu Y-Y, Chien Y-L et al. Determinants of maternal satisfaction with diagnosis disclosure of autism. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113(8):540-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2012.07.040

20. Curtiss SL, Ebata AT. The nature of family meals: A new vision of families of children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(2):441-52. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3720-9

21. Derguy C, Michel G, M’bailara K, Roux S, Bouvard M. Assessing needs in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A crucial preliminary step to target relevant issues for support programs. Intellect Dev Disabil 2015;40(2):156-66. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2015.1023707

22. Dinora P, Bogenschutz M, Lynch K. Factors That May Influence Parent Treatment Decision Making for Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2017;16(3-4):377-95. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1536710X.2017.1392395

23. Dinora P, Bogenschutz M. Narratives on the factors that influence family decision making for young children with autism spectrum disorder. J Early Interv. 2018;40(3):195-211. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815118760313

24. Frame KN, Casey LB. Variables influencing parental treatment selection for children with autism spectrum disorder. Child. Youth Serv Rev., Elsevier. 2019;106:1-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104464

25. Frye L. Fathers’ experience with autism spectrum disorder: Nursing implications. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016;30(5):453-63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.10.012

26. Gibson AN, Kaplan S, Vardell E. A survey of information source preferences of parents of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(7):2189-204. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3127-z

27. Grant N, Rodger S, Hoffmann T. Intervention decision-making processes and information preferences of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(1):125-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12296

28. Hays A, Butauski M. Privacy, disability, and family: Exploring the privacy management behaviors of parents with a child with autism. West J Commun. 2018;82(3):376-91. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2017.1398834

29. Hennel S, Coates C, Symeonides C, Gulenc A, Smith L, Price AMH et al. Diagnosing autism: Contemporaneous surveys of parent needs and paediatric practice.J Paediatr Child Health. 2016;52(5):506-11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13157

30. Hodgetts S, Zwaigenbaum L, Nicholas D, Profile and predictors of service needs for families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2015;19(6):673-83. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314543531

31. Huus K, Olsson LM, Andersson EE, Granlund M, Augustine L. Perceived needs among parents of children with a mild intellectual disability in Sweden. Scand J Disabil Res. 2017;19(4):307-17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2016.1167773

32. Kocabiyik OO, Fazlioğlu Y. Life Stories of Parents with Autistic Children.J Educ Train Stud. 2018;6(3):26-37. DOI: https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i3.2920

33. Lajonchere CM, Valente TW, Kreutzer C, Munsou A, Narayanan S, Kazemzadeh A et al. Strategies for disseminating information on biomedical research on autism to Hispanic parents. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(3):1038-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2649-5

34. Li M, Amuta A, Xu L, Dhar S, Talwar D, Jung E, Chen LS. Autism genetic testing information needs among parents of affected children: A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):1011-16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.12.023

35. Liu Y, Fisher K. Engaging with disability services: experiences of families from Chinese backgrounds in Sydney. Aust Soc Work. 2017;70(4):441-52. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2017.1324885

36. Lopez K, Magaña S, Xu Y, Guzman J. Mother’s Reaction to autism diagnosis: A qualitative analysis comparing Latino and white parents. J. Rehabil. 2018;84(1):41-50. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/openview/7a45da1b334b635ee838c4917b839179/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=37110

37. Mereoiu M, Bland C, Dobbins N, Niemeyer JA. Exploring perspectives on child care with families of children with autism. Early Child Res Pract. 2015;17(1):1-28. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284886923_Exploring_perspectives_on_child_care_with_families_of_children_with_autism

38. Molteni P, Maggiolini S. Parents’ perspectives towards the diagnosis of autism: An Italian case study research. JCFS. 2015;24(4):1088-96. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9917-4

39. Moro GL, Jenaro RC, Solano SM. Miedos, esperanzas y reivindicaciones de padres de niños con TEA. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. 2015;46(4):7-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/scero2015464724

40. Ntre V, Papanikolauo K, Triantafyllou K, Giannakopoulos, Kokkosi M, Kolaitis G. Psychosocial and Financial Needs, Burdens and Support, and Major Concerns among Greek Families with Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). IJCS.2018;11(2):985-95. Available from: http://internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/40_ntre_original_10_2.pdf

41. Pearson JN, Traficante AL, Denny LM, Malone K, Codd E. Meeting FACES: Preliminary findings from a community workshop for minority parents of children with autism in Central North Carolina. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(1):1-11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04295-4

42. Pejovic-Milovancevic M, Stankovic M, Mitkovic-Voncina M, Rudic N, Grujicic R, Herrare AS et al. Perceptions on support, challenges and needs among parents of children with autism: The Serbian experience. Psychiatr Danub. 2018;30(Suppl 6):354-54. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/beb3/26222a962cbd26f382b74a04f2a5c32b718b.pdf

43. Pickard KE, Ingersoll BR. Quality versus quantity: The role of socioeconomic status on parent-reported service knowledge, service use, unmet service needs, and barriers to service use. Autism. 2016;20(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315569745

44. Pickard K, Rowless S, Ingersoll B. Understanding the impact of adaptations to a parent-mediated intervention on parents’ ratings of perceived barriers, program attributes, and intent to use. Autism: Autism. 2019;23(2):338-49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317744078

45. Preece D, Symeou L, Stosic J, Troshanska J, Mavrou K, Theodorou E. Accessing parental perspectives to inform the development of parent training in autism in south-eastern Europe. Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2016;32(2):252-69. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1223399

46. Prendeville P, Kinsella W. The role of grandparents in supporting families of children with autism spectrum disorders: A family systems approach. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:738-49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3753-0

47. Rivard M, Lépine A, Mercier C, Morin M. Quality determinants of services for parents of young children with autism spectrum disorders. IJCYF. 2015;24(8):2388-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0041-2

48. Rivard M, Millau M, Magnan C, Mello C, Boulé M. Snakes and ladders: Barriers and facilitators experienced by immigrant families when accessing an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2019;31:519-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-018-9653-6

49. Roffeei SHM, Abdullah N, Basar SKR. Seeking social support on Facebook for children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(5):375-85. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.01.015

50. Ryan C, Quinlan E. Whoever shouts the loudest: Listening to parents of children with disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018;31:1-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12354

51. Tait K, Hu FFA, Sweller N, Wang W. Understanding Hong Kong Chinese families’ experiences of an autism/ASD diagnosis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(4):1164-83. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2650-z

52. Tekinarslan İÇ. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Experiences of Mothers before and after their children’s diagnosis and implications for early special education services. J Educ Train Stud. 2018;6(12):68-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i12.3692

53. Wallace LR. The impact of family autism camp on families and individuals with ASD. Qual Rep 2016;21(8):1441-53. Available from: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com.br/&httpsredir=1&article=2410&context=tqr/

54. Zajicek-Farber ML, Lotrecchiano GR, Long TM, Farber JM. Parental perceptions of family centered care in medical homes of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. JMCH. 2015;19(8):1744-55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1688-z

55. Zakirova-Engstrand R, Roll-Pettersson L, Westling-Allodi M, Hirvikoski T. Needs of Grandparents of Preschool-Aged Children with ASD in Sweden. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50:1941-57. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03946-w

56. Rogers SL, Dawson G, Vismara LA. TEA. Compreender e agir. Lisboa: Editora Lidel; 2015.

57. Mapelli LD, Baribieri MC, Castro GVDZB, Bonelli MA et al. Child with autistic spectrum disorder: Care from the family. Esc Anna Nery. 2018; 22(4):e20180116. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-EAN-2018-0116

58. Schroeder WK. Leveraging Social Media in #FamilyNursing Practice. J Fam Nurs. 2017;23(1):55-72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840716684228