|

Article

Lorena Chaparro-Díaz1

Sonia Carreño-Moreno2

Jennifer Rojas-Reyes3

1 ![]() 0000-0001-8241-8694 Universidad

Nacional de Colombia, sede Bogotá, Colombia olchaparrod@unal.edu.co

0000-0001-8241-8694 Universidad

Nacional de Colombia, sede Bogotá, Colombia olchaparrod@unal.edu.co

2 ![]() 0000-0002-4386-6053 Universidad

Nacional de Colombia, sede Bogotá, Colombia spcarrenom@unal.edu.co

0000-0002-4386-6053 Universidad

Nacional de Colombia, sede Bogotá, Colombia spcarrenom@unal.edu.co

3 ![]() 0000-0001-8962-5135 Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia jennifer.rojasr@udea.edu.co

0000-0001-8962-5135 Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia jennifer.rojasr@udea.edu.co

* Funding: Nursing School, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Call for support to health research projects - 60 years of the Nursing School 2019, Code: 45048.

** Financiación: Facultad de Enfermería, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Convocatoria para el apoyo a proyectos de investigación en salud - 60 años Facultad de Enfermería 2019, Código: 45048.

***Financiamento pela Faculdade de Enfermagem, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Edital para o apoio de projetos de pesquisa em saúde — 60 anos da Faculdade de Enfermagem, em 2019. Código: 45048.

Theme: Epistemology

Contribution to the discipline: This proposal for a specific situation theory advances theoretical knowledge and acknowledges that the caregiver role represents a transition that requires nursing support.

Received: 04/02/2022

Sent to peers: 16/05/2022

Accepted by peers: 20/06/2022

Approved: 14/07/2022

To reference this article / Para citar este artículo / Para citar este artigo: Chaparro-Díaz L, Carreño-Moreno S, Rojas-Reyes J. Adopting the Role of Caregiver of Chronic Patients: Specific Situation Theory. Aquichan. 2022;22(4):e2242. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2022.22.4.2

Abstract

Objective: To present the

proposal for a specific situation theory on adopting the role of caregiver of

chronic patients.

Materials and

methods: Based

on Meleis and Im’s integrating

strategy, multiple information sources were employed to develop this theory.

Results: This prescriptive

theory derives from Meleis’ mid-range theory based on

an exhaustive literature review and the authors’ practical and research

experience. The information was integrated into core concepts such as

caregiver’s transition, caregiver role insufficiency, nature and conditions of

the transition, nursing transitional care for the caregiver, and healthy

transition. Assertions were also derived, such as the adoption of the caregiver

role influencing the response patterns or the result indicators related to the

caregiver’s quality of life and perception of burden. Finally, a theoretical

process and an empirical indicator called ROLE are described.

Conclusions: This theoretical

development recognizes the process faced by caregivers in adopting their role

in the care of chronic patients and guides possible nursing interventions to

favor a healthy transition.

Keywords (Source DeCS): Caregivers; chronic disease; nurse; nursing theory; role; transitional care.

Resumen

Objetivo: dar a

conocer una propuesta de teoría de situación específica sobre la adopción del

rol del cuidador del paciente crónico.

Materiales y métodos: basados en la estrategia integradora de Meleis e Im, se emplearon múltiples fuentes de información

para el desarrollo de esta teoría.

Resultados: esta teoría de carácter prescriptivo se deriva de la teoría de rango

medio de las transiciones de Meleis, a partir de una

exhaustiva revisión de literatura y de la experiencia práctica e investigativa

de las autoras. Se integró la información en conceptos centrales como:

transición del cuidador, insuficiencia del rol de cuidador, naturaleza de la

transición, condiciones de transición, cuidado transicional de enfermería al

cuidador y transición saludable; se derivaron afirmaciones como que la adopción

del rol de cuidador influencia los patrones de respuesta o indicadores de

resultado relacionados con la calidad de vida y la percepción de sobrecarga del

cuidador; se describe un proceso teórico y un indicador empírico denominado

ROL.

Conclusiones: este desarrollo teórico permite reconocer el proceso

que el cuidador enfrenta para adoptar su rol en el cuidado al paciente crónico

y orientar posibles intervenciones de enfermería para favorecer una transición

saludable.

>Palabras clave (Fuente DeCS): Cuidado de transición; cuidadores; enfermedad crónica; enfermería; rol; teoría de enfermería.

Resumo

Objetivo: apresentar uma proposta de teoria de uma situação

específica sobre a adoção do papel de cuidador do paciente crônico.

Materiais e

métodos: com base na estratégia integrativa de Meleis e Im,

foram utilizadas múltiplas fontes de informação para o desenvolvimento desta

teoria.

Resultados: esta teoria prescritiva deriva da teoria de médio

alcance das transições de Meleis, a partir de uma exaustiva revisão da

literatura e da experiência prática e de pesquisa dos autores. As informações

foram integradas em conceitos centrais como: transição do cuidador,

insuficiência do papel do cuidador, natureza da transição, condições de

transição, cuidados de transição de enfermagem para o cuidador e transição

saudável; com afirmações que indicam que a adoção do papel de cuidador

influencia os padrões de resposta ou indicadores de resultados relacionados à

qualidade de vida e à percepção de sobrecarga do cuidador; apresenta-se a

descrição de um processo teórico e um indicador empírico denominado ROL.

Conclusões: este desenvolvimento teórico permite reconhecer o

processo que o cuidador enfrenta para adotar seu papel no cuidado ao paciente

crônico e orientar possíveis intervenções de enfermagem para favorecer uma

transição saudável.

Palavras-chave (Fonte: DeCS) Cuidadores; cuidado transicional; doença crônica; enfermagem; papel (figurativo); teoria de enfermagem.

Introduction

In its 2020 report on deaths between 2000 and 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) (1) reveals a considerable increase in deaths due to heart diseases, dementia, and diabetes. This epidemiological profile evolved during those years and is now prevalent in the population. It also states that people live longer when given access to health services and treatments, although with more disabilities; consequently, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, strokes, lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caused 100 million healthy life years lost compared to 2000.

The panorama above proves that Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases (CNCDs) create some degree of disability and dependence; thus, constant patient monitoring is necessary to manage the disease and even for self-care. Here, the family caregiver role arises (2, 3). There is extensive evidence of the impact of chronic diseases not only on people but also on their families and caregivers.

Generally, family caregivers have a kinship or closeness tie with the people with CNCDs. When they decide to assume the care responsibility, they transform their entire life and routine, facing the loss of their jobs due to the role transition, a situation frequently associated with the perception of burden (4-6).

Family caregivers are often not prepared to perform the new role (7-10); however, all roles can be learned (11), and it is, therefore, possible to advance from ineffective performance towards a favorable transition in role adoption (12). Some authors have found that new skills (8, 9), relationships, and coping strategies (13) are developed during the transition.

Adopting the caregiver role is the response to a transition process, which has been addressed from different theoretical perspectives, such as Roy’s Adaptation Model (14) and Meleis’ Theory of Transitions (15). However, considering the conceptual progress, the empirical evidence, and the practical experience in the role of the family caregiver of a person with a CNCD, the concept represents a specific construct for this population segment. Accordingly, this article aims to present a proposal for a specific situation theory about adopting the role of caregiver of chronic patients, following Meleis and Im’s postulates (16) for theoretical progress in the discipline.

Background

The concept of adopting the caregiver role emerges from several research studies about caring for chronic patients and their families. In this search about the experiences in caring for these people, two qualitative research studies were consolidated (17, 18). They showed a series of categories that conclude that chronic disease situations are associated with role adoption phases (17), evidenced when caregivers state that they do not feel prepared to take on the new role. Although they fulfill these complex duties with insecurity and fatigue, then, with repetition, the instrumental tasks are performed more skillfully, allowing the reorganization of life (18). Thus, the caregiver role transition is characterized by the organization, performance of, and responses toward the role (19).

When determining that role adoption is related to a caregiver transition process, an exploration was made from different nursing theoretical approaches to link concepts that met the definition of this concept. In this respect, Meleis’ mid-range Theory of Transitions (12) was the one that could best describe this construct; therefore, it will be the theoretical grounds to develop the theory herein presented.

According to several authors (20-22), situational theories are a novelty, and those that have been developed in the last few decades have followed different paths; some derive from practice, others from research, and others from systematic literature reviews and models or theories inherent to nursing. In this plurality of theorization paths, some integrate several perspectives that make them more strict and valid, making it necessary to explain a specific phenomenon in a particular context (20) and that the nursing community identifies itself with what is therein presented. Such being the case, this situational theory derives from an integrative process between research, practice, and an already established mid-range theory.

Methodology

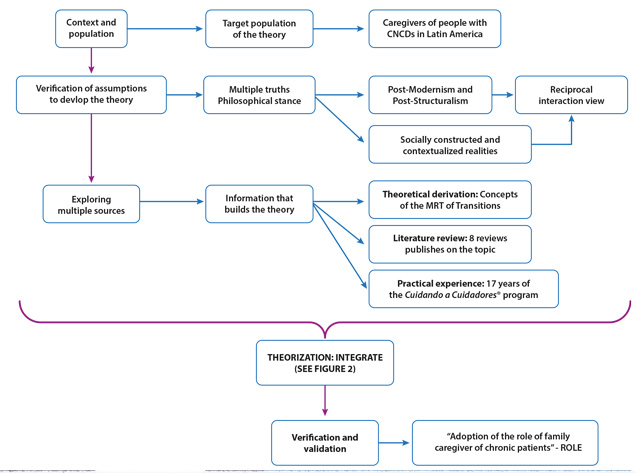

To elaborate on this specific situation theory, Meleis and Im’s integrative strategy (16) was considered, as explained in Figure 1. This integrated strategy meets the “multiple truths” criterion as an essential assumption to develop specific situation theories in nursing.

Figure 1. Steps of the integrative strategy to develop the situational theory

Source: Own elaboration based on the Meleis and Im’s steps (16).

The integrative approach proposed the points to the process of developing the theory as being dynamic, cyclic, and changing over time. Thus, it is necessary to welcome this plurality and remain open to the potential growth of theoretical nursing, with flexibility in the application of the steps presented by various authors. Consequently, the results will present most of the proposed steps to meet the objective.

Ethical considerations

This proposal for a specific situation theory is the result of integrating various research studies that have allowed elaborating a thematic line; therefore, this article gathers this information and respects intellectual property rights by following the applicable citation style (23).

Results

In consonance with the methodology selected, the context and target population of this theoretical proposal are described within the results. Subsequently, the verification of the assumptions is presented, setting out the situational theory meta-paradigm’s philosophical stance and concepts. The next stage is the exploration of multiple sources, where the elements taken from the theoretical derivation, the literature review, and the authors’ practical experience in building this proposal are explained. From this point, theorization is conducted, integrating this information into concepts and theoretical hypotheses; a theoretical process is also completed to describe how this phenomenon manifests itself. Finally, an approach to verifying and validating the theory is made, presenting the empirical indicator linked to this specific situation theory.

Context and population

Caregivers of people with CNCDs can be characterized by gender, age, schooling, occupation, economic level, bond with the sick person, health status, and time devoted to care. In Latin America, eight out of ten people who care for a family member are women; the studies reveal that nearly 90 % belong to this gender and are the ones performing the heaviest routine care actions that require more dedication (24).

Regarding age, most caregivers are younger than the person cared for, except in the case of children, where the mothers provide such care, and the age relationship is inverted (25). In this sense, the caregiver’s bond with the sick person is primarily out of kinship (daughter/son or spouse); however, in other cultures, the caregivers can be friends, neighbors, or institutions (24, 25). Most of these caregivers state having low or mid schooling levels, which corresponds to incomplete Elementary or High School; this is also associated with the socioeconomic difficulties generated by the care provided and the exclusive dedication it often demands, thus limiting development opportunities for the caregiver in other spheres (6).

Consequently, caregivers experience a burden associated with depression symptoms, with a 0.14 % risk (26). Regarding working life, the care task and the job generate conflicts; low work performance also influences the onset of depression, manifested in female caregivers (27). In this accumulation of multiple responsibilities and caregiver roles, being a spouse, mother/father, or son/daughter also implies dedication and time (28). For some, having a partner is a facilitating factor, whereas, for others, it is but another demand; even so, 80 % of these caregivers state counting on other people’s support for care activities (29) to better cope with the role transition.

2. Verification of assumptions to develop the theory

From the philosophical perspective under which this specific situation theory is advanced, the principles of Post-Modernism and Post-Structuralism are recognized, responding to a pluralist stance regarding knowledge (30). These two approaches accept the socially-constructed realities, reflecting on how the meanings of specific experiences have been transformed and conveyed, a process in which there is room for deconstructing what already exists and exploring multiple interpretations (30). In relating these postulates to adopting the caregiver role, acting as a family caregiver is considered a social representation built on the prevalence of chronic diseases. This role emerged and has gradually been transformed as it gained recognition. This role comes with different care meanings, where, as experience increases, the beliefs about care are deconstructed, others are built, and the caregiver is empowered (31); in summary, there is a plurality of perspectives about adopting the caregiver role.

From the nursing disciplinary perspective, the structure of this theoretical proposal is in line with the organization of nursing knowledge put forward by Fawcett (32) with the concept of knowledge holarchy, involving the worldview and meta-paradigm concepts.

The worldview on which this theoretical proposal is grounded is reciprocal interaction (32), coinciding with its conception; according to this perspective, the concepts of the nursing meta-paradigm in this situational theory can be defined as follows:

· Human being: Family caregivers are human beings with multiple needs to perform their role correctly, which impair their integrality as holistic beings. They are vulnerable beings, though active in their process, counting on autonomy and determination to learn, relate to other people, make decisions, solve problems, anticipate the care needs of their family members, and attribute meaning to the adoption of the caregiver role.

· Health: A process in which family caregivers interact with significant others in constructing their role. It also depends on the caregivers’ perception of burden, social support, and satisfaction with performing other roles in their everyday life.

· Nursing: Care with solid knowledge about the needs of chronic patients and their family caregivers. The goal of the care process is to achieve a healthy transition to the family caregiver role in its adoption.

· Environment: The place where significant interactions between human beings occur in constructing the caregiver role. The socio- political context in which the caregiver role has been built is also considered. Currently, society acknowledges family caregivers, and laws have been enacted to favor their work (33), supporting the adoption of the role when these provisions are followed.

3. Exploring through multiples sources

Several sources were employed to elaborate this proposal for a specific situation theory, such as a mid-range theory, a literature review, and practical experience, observing plurality of the knowledge that must be collected to build theories (16).

Theoretical derivation

From the conceptual point of view, this specific situation theory derives from Meleis’ Theory of Transitions. This Nursing Mid-Range Theory (MRT) emerges from the theory of the role, symbolic interactionism, the clinical practice experience, the systematic literature review, and four qualitative research studies (12).

The concept of the role that grounds Meleis’ MRT of Transitions refers to a set of conducts or behaviors, feelings, and goals that confer unity to a set of actions (11). The role is built up in the interaction with other people, as human behavior does not respond to an isolated stimulus but to a complex interaction with significant others, where each person’s roles are constructed, highlighting the importance of reciprocity in understanding the concept of role (34, 35).

Some assumptions and proposals from Afaf Meleis’ Theory of Transitions are condensed to understand the experience of transition in adopting the family caregiver role (34):

· Transition occurs when an individual ceases to be a family member of a healthy person to become the family caregiver of a chronic patient.

· Transition implies certain insufficiency of the family caregiver role, defined as difficulty knowing or performing the function or regarding the associated feelings and goals perceived by the caregiver or other people. This deficit is related to starting to complete the caregiver role.

· In essence, the transition is of the health-disease type because it occurs as a result of a change in the health status and implies facing the change and making adjustments to the roles, both of the sick person and the individual assuming the care responsibility. It is also situational, as it manifests itself in different stages of the life cycle.

· The transition pattern is multiple, simultaneous, and related, as it occurs concomitantly with other transitions such as hospital admission-stay-discharge, employed-unemployed, and being the former head of the home, among many others that could be listed and which are characteristic of the population of family caregivers.

· The response pattern to be evaluated is dexterity, measured based on the result indicator called “adoption of the role of family caregiver of chronic patients” (19, 36).

· Nursing therapy offers interventions for the caregivers’ knowledge and preparedness in this transition, generating a response pattern in adopting the family caregiver role.

Literature review

Multiple literature reviews (systematic and integrative) have been conducted about this phenomenon of care transition and family care in the Group for the Care of Chronic Patients and their Families research path. These reviews have already been published (18, 19, 37-42) and are synthesized to prepare this proposal for a specific situation theory.

The family caregiver transition is initiated abruptly by a significant event or specific change (a chronic disease of the person with a kinship or closeness tie) that requires new response patterns (38, 43, 44). Depending on the context and conditions in which this transition occurs, it can ease or hinder role adoption. Knowledge, beliefs, meanings, attitudes, and factors of the social system in which the caregiver acts are among these conditions (45). The time required for this transition is variable and depends on the nature of the change and its influences. Likewise, the transition flow is characterized by a period of confusion and denial regarding the task; it then presents a chaotic phase in which the meaning of the task is lost, and disorientation emerges. Finally, a new perspective is found in which the meaning of the task is different and new (46, 47).

The evident transition patterns are unique in each caregiver’s experience and are also multiple and sequential because they exert a wave effect over time. Each chronic patient’s crisis can pose new challenges and difficulties in the role, with the presence of simultaneous and unrelated patterns, because, in addition to the tasks with their sick family member, family caregivers must do chores inherent to other spheres, such as marriage, work, and development (46-48).

Family caregivers frequently display insufficiency in their role, derived from an incorrect definition of their functions, knowledge deficits, inadequate dynamics in their relationships with others, or adverse feelings related to the role. Regarding the functions and knowledge, the caregivers need more education in aspects related to the disease (44, 49), household chores, nutrition, reorganization of everyday life, and emotional elements (47, 48). The relationship with the rest of the family is affected by the caregivers’ isolation, who devote most of their time, attention, motivation, and energy to the care task (45, 48, 50). Regarding the feelings, family caregivers significantly impact their emotional sphere, which triggers depression, anxiety, and stress (47, 51), in addition to burden and adverse feelings such as uncertainty, anguish, pain, despair, fear, and hopelessness (50, 52).

The caregivers can also have difficulties performing their role, as it is a function that depends not only on them but also on interactions with other people, such as the sick person, the family, and the health team (53). Several indicators of caregiver role insufficiency have been reported in the literature, among which are adverse feelings, dysfunctional relationships, and lack of specific knowledge and skills to perform the role, especially regarding its organization (35, 54).

The expected result for the caregivers is that they are competent enough to perform their role, which is translated into their well- being and that of the significant others as a response pattern in an adequate transition of their role. The following are the primary response patterns of this transition: control of the sick person’s disease (54), problem-solving skills, mood (55, 56), and the caregiver’s quality of life perception.

Experiences based on practice

In its studies with family caregivers, the Nursing Care for Chronic Patients research group from the Nursing School at Universidad Nacional de Colombia recognized that the care burden was vital for them and involved their poor quality of life. Therefore, they designed the program called “Cuidando a Cuidadores®” (“Taking Care of Caregivers”) to meet the need for knowledge to provide care and adequately adopt the role, in addition to representing social support for the caregivers as care networks are created (57).

The program was created following Ngozy Nkongo’s three conceptual guidelines:

1. Knowledge, which implies knowing the needs, strengths, and weaknesses of the person cared for and the caregiver.

2. Value, which is obtained from the experience to become open to the needs of the present; it implies making decisions and seeking support and self-empowerment as subjects of rights.

3. Patience, which comprises the search for growth and meaning through exploration, expression, reflection, tolerance, and self-control in the face of disorganization of their role.

The program includes two levels. The first helps family caregivers of chronic patients to recognize themselves as such and to understand and value their experience in this role. It also motivates them to act as a support network for other caregivers, thus strengthening knowledge, value, and patience (57, 58). At the second level, the caregivers advance in their role to nurture themselves in terms of competencies based on knowledge, being, and doing, such as in the management of emotions, conflicts and grief, drug administration, healthy lifestyles, financial management, social support, care continuity, and use of care technologies, among others. These activities allow the caregivers to have time for themselves and reduce their perception of the burden of care (58).

The program was designed based on the available evidence, practical experience, and research-related contributions (57, 59). In general, the program expects that the caregivers discover their care experience and analyze it, identify their potentialities and limitations, recognize the gains from being caregivers, and get empowered in their role (59).

1. Theorizing: Concepts and theoretical hypotheses

Although it contains descriptive and predictive elements, this proposal for a specific situation theory is prescriptive. In this sense, it describes the role transition process in family caregivers of chronic patients and the nature of the transition (18, 38); it acknowledges the gender, age, dependence level, cognitive level, perception of a threat to life, spirituality, and social support factors as predictors of role adoption. Similarly, adopting the role predicts the response patterns or outcome indicators (6, 15, 60, 61). It is also prescriptive because it indicates how to provide transitional nursing care to caregivers through strategies such as role clarification, role trial, and role modeling (15, 59).

Core concepts

Role transition: A process that, for human beings, implies changes in their relationships with others, their expectations, and multidimensional skills (20).

Caregiver role insufficiency: The inadequate development of some of the processes implied in a role transition. It can result from a poor definition of functions, the internal dynamics in the role relationships, or lack of knowledge about the role behaviors and the associated feelings and goals. Role insufficiency hinders progression towards health and well-being and, consequently, to a healthy transition (62).

Nature of the transition: The pattern that rules the transition, characterized as multiple and related; in other words, the most usual is for each person to experience numerous related transitions at the same time (34). It is both of the health-disease and situational type, with multiple, simultaneous, and associated patterns. It has critical points such as the caregiver’s gender, age, previous experiences as a caregiver, the daily hours devoted to care, the time as a caregiver, the dependence level of the person cared for, the cognitive state of the person cared for, and the perception of a threat to life imposed by the disease.

Conditions of the transition: Influential conditions in a person’s path towards a transition. They can facilitate or inhibit factors, including meanings, beliefs, cultural attitudes, socioeconomic level, preparedness, and knowledge (63).

Transitional nursing care for caregivers: Nursing can favor the adoption of the role through strategies such as role clarification, role trial, and role modeling (15, 20, 34):

· Role clarification: It responds to the cognitive sphere, where caregivers must be clear about what to do and how. This activity is helpful in the initial stages when caregivers need simple and concrete instructions for the activities they should carry out, focused on the instrumental aspect.

· Role trial: Once caregivers are faced with the role, they need to put it into practice to be able to progress. Thus, trying out the role is a valuable tool to prepare the caregivers to cope with frequent care-related problems, as it will always be easier to face a situation to which they have at least been exposed. The family caregiver role can be learned in simulated scenarios.

· Role modeling: The role is performed through interaction with others, which is why it is helpful to interact with people with similar functions. Based on this principle, it is beneficial for the caregivers to interact as much as possible with the health team and other caregivers. Learning from examples and experiences ensures knowledge integration and availability to perform the role adequately.

Healthy transition: The transition is when people change their behavior and acquire a certain degree of self-awareness and mastery of new knowledge and skills to adapt to the new condition or role positively.

Theoretical hypotheses

1. Regarding the transition conditions, women and older people enjoy healthier transitions towards adopting the caregiver role (64).

2. Regarding age, the best transitions occur in caregivers of children and older adults since, due to their development stage, they are more used to being cared for (65, 66).

3. More complex and challenging transitions have been documented in the case of diseases that impair cognition compared to those that affect the physique of a person with a CNCD (67).

4. Low incomes imply worse conditions to perform the caregiver role, mainly when the family’s financial resources are mobilized towards the needs of the person cared for, forgetting that the caregiver also has needs (17, 61).

5. The role is a social construction resulting from interacting with significant others in such a context. In this case, the first significant other is the person cared for, followed by the family, the health team, and support networks (68).

6. Although the expected behaviors can be precise, people may not act accordingly to adopt a given role. For example, it is frequent for family caregivers to know that it is healthy to have a break from care; however, many of them refuse to be relieved (69).

7. Spirituality and social support favor interactions with other people that go through similar health situations; therefore, counting on these aspects assists in a healthy transition to adopting the caregiver role (70).

8. Whether adoption of the caregiver role is healthy will exert a direct influence on the response patterns or outcome indicators related to quality of life and the caregiver’s perception of burden, anxiety, depression, and loneliness (71).

9. Transitional nursing care offers the caregivers several tools based on teaching the role through clarification, training, trial, interaction with others, and role modeling (15).

2. Theoretical process

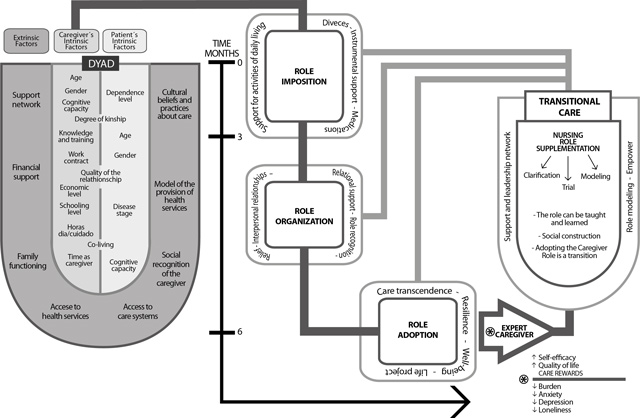

The scheme shown in Figure 2 summarizes concepts from electronics: There is an input related to the intrinsic factors of the actors involved in the process; subsequently, there are three phases that can be sequential and which account for a caregiver’s possibilities until adopting their role. Transitional care is the intervention modality in each of the phases. It can be integrated into the caregivers’ expertise, which, over time and due to adequate coping and self-efficacy strategies, can achieve higher awareness of their role.

Figure 2:. Scheme of the specific situation theory called “Adopting the role of family caregiver of a chronic patient”

Source: Own elaboration.

The theory’s scheme consists of three inter-related parts that account for a caregiver’s role adoption process from moment zero: diagnosis of the person cared for and the goal of becoming an expert caregiver.

The first part simulates a container with input elements from the dyad (person with a chronic condition and caregiver) that can be classified into intrinsic or own factors and extrinsic or context- related factors. The factors act as a starting point and correspond to the transition conditions, which can ease or hinder role adoption according to the theoretical postulates.

The second component consists in the role adoption phases or moments, which are presented as a timeline but also as a process line; consequently, it is predicted that there will be role imposition between months zero and three, role organization between months three and six and, finally, role adoption itself from month six onwards. Each phase has several concentric squares that indicate the key activities where the caregivers should be supported to advance to the next step.

The third component corresponds to transitional care, its characteristics, strategies, and results; among the latter, the process of becoming an expert caregiver stands out as the primary outcome, with the self-efficacy level, quality of life, perception of care rewards, burden, anxiety, depression, and loneliness as its indicators.

3. Validation and verification of the theory

Regarding verification of this specific situation theory, there is an empirical indicator called “Adoption of the role of family caregiver of chronic patients” (19), which derives from this theoretical proposal. According to Hopcey and Morse (72), it is necessary to acknowledge that the maturity of a concept follows the pragmatism criterion; in other words, the empirical indicators are manifestations of the concept. This is a way to validate a theory, and, in our case, the instrument in question derives from the concepts that constitute this theoretical proposal, objectifying the role adoption process.

In parallel to the theory, this instrument was published in a previous study (19, 36), describing its preparation and validation. For this empirical indicator, the conceptual bases of Meleis’ Theory of Transitions and the empirical evidence were employed, which indicated that role adoption has three attributes: performance of the role (tasks), role organization, and responses towards the role. It has 22 items assessed on a Likert-type scale with five answer options that vary from “Never” to “Always.” Its validation was performed in 2017 with eight experts from Colombia, Chile, Mexico, Peru, and Argentina for content validity, 60 caregivers for face validity, and 110 caregivers for construct validity. The results showed construct validity through a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test result of 0.835 and reliability through a Cronbach alpha of 0.816 (19, 36).

To the present day, this instrument has been employed in several research studies in the CNCD context; however, no results are yet available, as some surveys are ongoing and others are in the publication submission process.

Implications for nursing

Nursing professionals working in the care of people with chronic diseases and their caregivers can use this theory to understand the process undergone by the dyad, in addition to retargeting their interventions to ensure the adoption of the caregiver role. In the long-term, this improves quality of life, the perception of the care burden, anxiety, depression, and loneliness, as there is proper role response, organization, and performance.

For research, this theory can guide future studies that explore various intervention strategies in populations comprised of people with chronic diseases and their caregivers, with characteristics inherent to each disease and even of each culture in which the caregiver role is adopted as a differentiating factor.

Regarding education in nursing, it can be considered that the theory would not only allow undergraduate and graduate students to see the theory-practice gap reduced but also enhance their participation in monitoring the dyad during their practice in any context where they perform their learning activities. There are already initial experiences on teaching in practice scenarios where this situational theory guides interventions in programs targeted at caregivers.

Conclusions

It was possible to set out a specific situation theory on adopting the role of caregiver of chronic patients derived from multiple sources. Prescriptive in nature, this theory presents the transition process followed by the caregivers to adopt this role healthily.

The transitional care provided to the caregiver also progresses and ceases to be centered on instrumental and fundamental aspects to start focusing on role organization, life restructuring, and, finally, reflection and signification of the role. So, the care approach from the transitional perspective goes beyond the educational and cognitive interventions, as it is from strategies to teach the role that a healthy transition can be achieved.

Limitations. As this theoretical proposal is based on evidence and practical expertise, it will require future changes because theoretical knowledge is continuously growing. It is not possible to delimit the theoretical and practical paths only with this theoretical approach. With the conceptual evolution in the development of nursing theories, this proposal will continue to be validated or rejected (21, 22).

Acknowledgments. We thank the caregivers from the “Cuidando a Cuidadores®” program of Universidad Nacional de Colombia, undergraduate and graduate students, and colleagues from Colombia and Latin America. They invited us to reflect on the fact that theoretical developments allow positioning our continent as a disciplinary knowledge niche that improves the care provided to people with chronic diseases and their caregivers.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

This paper derives from the authors’ experience in research, extension, innovation, and teaching in the “Family caregivers of chronic patients” research line.

References

1. Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Principales causas de muerte y discapacidad en el mundo: 2000-2019 [en línea]. OMS; 2020 [actualizada 09 de diciembre de 2020; acceso 05 de marzo de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/09-12-2020-who-reveals-leading-causes-of-death-and-disability-worldwide-2000-2019

2. Stawnychy MA, Teitelman AM, Riegel B. Caregiver autonomy support: a systematic review of interventions for adults with chronic illness and their caregivers with narrative synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2021 Apr;77(4):1667-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14696

3. Schulman-Green D, Feder SL, Dionne-Odom JN, Batten J, En Long VJ, Harris Y, Wilpers A, Wong T, Whittemore R. Family Caregiver support of patient self-management during chronic, life-limiting illness: a qualitative metasynthesis. J Fam Enfermeras. 2021; 27(1):55-72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840720977180

4. Xie H, Cheng C, Tao Y, Zhang J, Robert D, Jia J, Su Y. Quality of life in Chinese family caregivers for elderly people with chronic diseases. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016 Jul 6;14(1):99. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0504-9

5. Yu Y, Tang BW, Liu ZW, Chen YM, Zhang XY, Xiao S. Who cares for the schizophrenia individuals in rural China - A profile of primary family caregivers. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;84:47-53. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.04.002

6. Carreño S, Chaparro-Díaz L. Agrupaciones de cuidadores familiares en Colombia: perfil, habilidad de cuidado y sobrecarga. Pensamiento Psicológico. 2017;15(1):87-101. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S1657-89612017000100007&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es

7. Chaparro L, Barrera-Ortiz L, Vargas-Rosero E, Carreño-Moreno SP. Mujeres cuidadoras familiares de personas con enfermedad crónica en Colombia. Rev Cienc Cuidad. 2016;13(1):72-86. Disponible en: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/colombia/resource/es/biblio-906689

8. Van der Werf HM, Luttik MLA, De Boer A, Roodbol PF, Paans W. Growing up with a chronically ill family member-the impact on and support needs of young adult carers: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):855. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020855

9. Mamom J, Daovisan H. Listening to caregivers’ voices: the informal family caregiver burden of caring for chronically ill bedridden elderly patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):567. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010567

10. Lee M, Ryoo JH, Campbell C, Hollen PJ, Williams IC. Exploring the challenges of medical/nursing tasks in home care experienced by caregivers of older adults with dementia: An integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(23-24):4177-89. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15007

11. Biddle BJ. Role theory expectations, identities, and behaviors. Academic Press; 1979.

12. Meleis AI. Transitions Theory. Middle Range and Situation Specific Theories in Nursing Research and Practice. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2010.

13. Teixeira RJ, Applebaum AJ, Bhatia S, Brandão T. The impact of coping strategies of cancer caregivers on psychophysiological outcomes: an integrative review. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:207-15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S164946

14. Cuevas-Cancino JJ, Moreno-Pérez NE, Jiménez-González MJ, Padilla-Raygoza N, Pérez-Zamora I, Flores-Padilla L. Efecto de la psicoeducación en el afrontamiento y adaptación al rol de cuidador familiar del adulto mayor. Enferm Univ. 2019;16(4):390-401. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/eneo.23958421e.2019.4.585

15. Carreño Moreno S. El cuidado transicional de enfermería aumenta la competencia en el rol del cuidador del niño con cáncer. PSIC. 2016;13(2-3):321-32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5209/PSIC.54439

16. Im EO. Development of situation-specific theories: an integrative approach. En Im EO, Meleis A (ed.). Situation specific theories: development, utilization and evaluation in nursing. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2021. pp. 49-68.

17. Chaparro Díaz L. Cómo se constituye el “vínculo especial” de cuidado entre la persona con enfermedad crónica y el cuidador familiar. Aquichan; 2011;11(1):7-22. Disponible en: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/lil-635386

18. Carreño Moreno SP, Chaparro Díaz L. Reconstruyendo el significado de calidad de vida de los cuidadores en el cuidado: una metasíntesis. Av Enferm. 2015;33(1):55-66. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/av.enferm.v33n1.48103

19. Carreño Moreno S, Chaparro Diaz L. Adopción del rol del cuidador familiar del paciente crónico: Una herramienta para valorar la transición. Rev Investig Andin. 2018;20(36):39-54. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.33132/01248146.968

20. Meleis AI. Theoretical nursing: development and progress. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012 (5a. Ed.).

21. Im EO, Meleis A. Situation-specific theories: philosophical roots, properties, and approach. In: Im EO, Meleis A (ed.). Situation specific theories: development, utilization and evaluation in nursing. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2021. pp. 13-28.

22. Fawcett J. Middle-range theories and situation-specific theories: similarities and differences. In: Im EO, Meleis A (ed.). Situation specific theories: development, utilization and evaluation in nursing. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2021. pp. 39-48.

23. Comisión del Acuerdo de Cartagena. Decisión Andina 351. Régimen común sobre derecho de autor y derechos conexos. 1993. Disponible en: https://cdr.com.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/decisin-andina-351-de-1993.pdf

24. Barrera-Ortiz L, Pinto-Afanador N, Sánchez-Herrara B, Carrillo-González G, Chaparro-Díaz L. The family caregiver’s situation. En: Barrera Ortiz L, Pinto Afanador N, Sánchez Herrara B, Carrillo González G, Chaparro Díaz L. (ed). Caring for caregivers: family caregivers of patients with chronic illness. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2019. pp. 45-79. Available form: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/76166

25. Koumoutzis A, Cichy KE, Dellmann-Jenkins M, Blankemeyer M. Age Differences and similarities in associated stressors and outcomes among young, midlife, and older adult family caregivers. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2021;92(4):431-49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415020905265

26. Del-Pino-Casado R, Rodríguez Cardosa M, López-Martínez C, Orgeta V. The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in careers of older relatives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;29;14(5):e0217648. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217648

27. Badawy, P. J. and Schieman, S. When family calls: how gender, money, and care shape the relationship between family contact and family-to-work conflict. J Fam Issues. 2020; 41(8):1188–213. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19888769

28. Daley S, Murray J, Farina N, Page TE, Brown A, Basset T, Livingston G, Bowling A, Knapp M, Banerjee S. Understanding the quality of life of family careers of people with dementia: development of a new conceptual framework. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(1):79-86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4990

29. Flores M, Fuentes H, González G, Meza I, Cervantes G, Valle M. Main characteristics of the informal primary caregiver of hospitalized older adults. Nure Inv. 2017;14(88):1-16. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03324556

30. Gadea CA. El interaccionismo simbólico y sus vínculos con los estudios sobre cultura y poder en la contemporaneidad. Sociológica. 2018;33(95):39-64. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0187-01732018000300039&lng=es&tlng=es

31. Neves V, Sanna, MC. Conceitos e práticas de ensino e exercício da liderança em Enfermagem. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2016;69(4):733-40. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167.2016690417i

32. Fawcett J, Garity J. Evaluating Research for Evidence-Based Nursing Practice. F.A. Davis; 2008.

33. Ministerio de Salud. Manual de cuidado a cuidadores de personas con trastornos mentales y/o enfermedades crónicas discapacitantes. Convenio 547 de 2015 MSPS – OIM. Colombia; 2016.

34. Meleis, AI. Transitions theory. In: Smith MC, Parker ME (Eds.). Nursing theories and nursing practice. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 2015. pp. 361-80.

35. Schumacher KL, Jones PS, Meleis AI. Helping elderly persons in transition: A framework for research and practice. In: Swanson EA, Tripp-Reimer T (Eds.). Life transitions in the older adult: issues for nurses and other health professionals. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1999. pp. 1-26.

36. Arias M, Carreño S, Chaparro L. Validity and reliability of the scale, role taking in caregivers of people with chronic disease, ROL. Int Arch Med. 2018;11(34):1-10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3823/2575.

37. Esquivel Garzón N, Carreño Moreno S, Chaparro Díaz L. Rol del cuidador familiar novel de adultos en situación de dependencia: Scoping Review. Rev Cuid. 2021;12(2): e1368. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15649/cuidarte.1368

38. Carreño-Moreno S, Chaparro-Díaz L, Blanco Sánchez, P. Cuidador familiar del niño con cáncer: un rol en transición. Rev Latinoam Bioet. 2017;17(2):18-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18359/rlbi.2781

39. Rojas-Reyes J, Chaparro-Díaz L, Carreño-Moreno SP. El rol del cuidador a distancia de personas con enfermedad crónica: scoping review. Rev Cienc Cuidad. 2021;18(1):81-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22463/17949831.2447

40. Sánchez-Herrera B, Carrillo GM, Chaparro-Díaz L, Carreño SP, Gómez OJ. Concepto carga en los modelos teóricos sobre enfermedad crónica: revisión sistemática. Rev Salud Pública. 2016;18(6):976-85. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/rsap.v18n6.53210

41. Arias-Rojas M, Carreño Moreno S, Chaparro Díaz L. Incertidumbre ante la enfermedad crónica. Revisión integrativa. Rev Latinoam Bioet 2019;19(1):93-106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18359/rlbi.3575

42. Chaparro Díaz L, Carreño Moreno S, Arias-Rojas M. Soledad en el adulto mayor: implicaciones para el profesional de enfermería. Rev Cuid. 2019;10(2):e633. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15649/cuidarte.v10i2.633

43. Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Wells R, Barnato AE, Taylor RA, Rocque GB, Turkman YE, Kenny M, Ivankova NV, Bakitas MA, Martin MY. How family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer assist with upstream healthcare decision-making: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;13;14(3):e0212967. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212967

44. Sagbakken M, Spilker RS, Ingebretsen R. Dementia and migration: family care patterns merging with public care services. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(1):16-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317730818

45. Zegaczewski T, Chang K, Coddington J, Berg A. Factors related to healthy siblings’ psychosocial adjustment to children with cancer: an integrative review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(3):218-27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454215600426

46. Yu DSF, Cheng ST, Wang J. Unravelling positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: An integrative review of research literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;79:1-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.008

47. Fields B, Makaroun L, Rodriguez KL, Robinson C, Forman J, Rosland AM. Caregiver role development in chronic disease: A qualitative study of informal caregiving for veterans with diabetes. Chronic Illn. 2022;18(1):193-205. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395320949633

48. Burgdorf, J, Roth, DL, Riffin, C, et al. Factors associated with receipt of training among caregivers of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6): 833-35. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8694

49. Whitlatch CJ, Orsulic-Jeras S. Meeting the informational, educational, and psychosocial support needs of persons living with dementia and their family caregivers. Gerontologist. 2018;58(suppl. 1):S58-S73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx162

50. Moreno CS, Palomino MP, Moral FL, Frías OA, del-Pino CR. Problemas en el proceso de adaptación a los cambios en personas cuidadoras familiares de mayores con demencia. Gac Sanit. 2016;30(3):201-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.02.004

51. Nam GE, Warner EL, Morreall DK, Kirchhoff AC, et al. Understanding psychological distress among pediatric cancer caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(7):3147-155. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3136-z

52. Gérain P, Zech E. Informal Caregiver Burnout? Development of a theoretical framework to understand the impact of caregiving. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1748. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01748

53. Liu H, Yang C, Cheng H, Wu C, Chen C, Shyu YL. Family caregivers’ mental health is associated with postoperative recovery of elderly patients with hip fracture: a sample in Taiwan. J Psychosom Res. 2017;78(5):452-58. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.02.002

54. Plank A., Mazzoni V., Cavada L. Becoming a caregiver: new family carers’ experience during the transition from hospital to home. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:2072-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04025.x

55. Steenfeldt VØ, Aagerup LC, Jacobsen AH, Skjødt U. Becoming a family caregiver to a person with dementia: a literature review on the needs of family caregivers. SAGE Open Nurs. 2021;7:23779608211029073. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608211029073

56. Womack JL, Lilja M, Isaksson G. Crossing a line: a narrative of risk-taking by older women serving as caregivers. J Aging Stud. 2017;41:60-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2017.04.002

57. Grupo Cuidado de enfermería al paciente crónico. Cuidadores. Universidad Nacional de Colombia [consultado 01 de abril del 2021]. Disponible en: http://www.gcronico.unal.edu.co/cuidadores/

58. Barrera Ortiz L, Pinto Afanador N, Sánchez Herrara B, Carrillo González G, Chaparro Díaz L. “Caring for caregivers” program. In: Barrera Ortiz L, Pinto Afanador N, Sánchez Herrara B, Carrillo González G, Chaparro Díaz L. (ed). Caring for caregivers: family caregivers of patients with chronic illness. Bogotá, Colombia: Universidad Nacional de Colombia; 2019. pp. 127-70. Disponible en: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/76166

59. Carreño S, Chaparro L, Criado L, Vega O, Cuenca I. Magnitud de efecto de un programa dirigido a cuidadores familiares de personas con enfermedad crónica. NOVA. 2018;16(29):11-20. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/nova/v16n29/1794-2470-nova-16-29-00011.pdf

60. López León A, Carreño Moreno S, Arias-Rojas M. Relationship between quality of life of children with cancer and caregiving competence of main family caregivers. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2021;38(2):105-15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454220975695

61. Rativa Velandia M, Carreño Moreno SP. Family economic burden associated to caring for children with cancer. Invest Educ Enferm. 2018;36(1):e07. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iee.v36n1e07

62. Lee K, Puga F, Pickering CEZ, Masoud SS, White CL. Transitioning into the caregiver role following a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or related dementia: A scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;96:119-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.007

63. Ferrell BR., Kravitz K, Borneman T, Friedmann ET. Family caregivers: a qualitative study to better understand the quality-of-life concerns and needs of this population. Clin. Oncol. Nurs. 2018. 22(3): 286-94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1188/18.CJON.286-294

64. Chaparro-Díaz L, Barrera-Ortiz L, Vargas-Rosero E, Carreño-Moreno SP. Mujeres cuidadoras familiares de personas con enfermedad crónica en Colombia. Rev Cienc Cuidad. 2016;13(1):72-86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22463/17949831.7361

65. Carrillo GM, Carreño SP, Sánchez LM. Competencia para el cuidado en el hogar y carga en cuidadores familiares de adultos y niños con cáncer. Rev Investig Andin. 2018;20(36):87-101. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33132/01248146.971

66. Fenton ATHR, Keating NL, Ornstein KA, et al. Comparing adult-child and spousal caregiver burden and potential contributors. Cancer. 2022;128(10):2015-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34164

67. Reed C, Belger M, Dell’agnello G, et al. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease: differential associations in adult-child and spousal caregivers in the GERAS observational study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2014;4(1):51-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1159/000358234

68. Higginson A, Forgeron P, Dick B, Harrison D. Moving on: A survey of Canadian nurses’ self-reported transition practices for young people with chronic pain. Can J Pain. 2018;2(1):169-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/24740527.2018.1484663

69. De La Cuesta-Benjumea C. “Estar tranquila”: la experiencia del descanso de cuidadoras de pacientes con demencia avanzada. Enferm Clin. 2009;19(1):24-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2008.07.0

70. Panader-Torres A, Cerinza-León K, Echavarría-Arévalo X, Pacheco-Hernández J, Hernández-Zambrano S. Experiencias de educación interpares para favorecer el autocuidado del paciente oncológico. Duazary. 2020;17(2):45-57. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21676/2389783X.3234

71. Del-Pino-Casado R, Priego-Cubero E, López-Martínez C, Orgeta V. Subjective caregiver burden and anxiety in informal caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0247143. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247143

72. Morse JM, Hupcey JE, Mitcham C, Lenz ER. Concept analysis in nursing research: a critical appraisal. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 1996;10(3):253-77. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9009821/