|

ARTICLE

Ana Carla Petersen de Oliveira Santos*

Thais Nogueira Piton**

Climene Laura de Camargo***

Mara Ambrosina de Oliveira Vargas****

Lara Máyra Jesus da Silva Almeida*****

Mirna Gabriela Prado Gonçalves Dias******

* ![]() 0000-0002-9816-1560

Hospitalar Universitário Professor Edgard Santos, Universidade Federal da

Bahia, Brazil.

0000-0002-9816-1560

Hospitalar Universitário Professor Edgard Santos, Universidade Federal da

Bahia, Brazil.

![]() carlapetersen@ufba.br

carlapetersen@ufba.br

** ![]() 0000-0002-6363-4428

Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

0000-0002-6363-4428

Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

*** ![]() 0000-0002-4880-3916

Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

0000-0002-4880-3916

Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

**** ![]() 0000-0003-4721-4260

Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil.

0000-0003-4721-4260

Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil.

***** ![]() 0000-0002-9076-0286 Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

0000-0002-9076-0286 Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

****** ![]() 0000-0003-2162-830X Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

0000-0003-2162-830X Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

1 This research was funded by Universidade Federal da Bahia under the Student Assistance Dean Office program (PROAE 4/2018). Support was also obtained from the Academic Excellence Program of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (PROEX-CAPES 364/2021), in the context of the Graduate Program in Nursing at Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil. Article extracted from the PhD thesis entitled “Institutional violence against hospitalized children from the perspective of companions and health professionals”, presented in 2021 at the Graduate Program in Nursing and Health of the Nursing School at Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil.

2 Esta investigación fue financiada por la Universidade Federal da Bahia gracias a la vicerrectoría de asistencia estudiantil, con el código (Proae 4/2018). También, se obtuvo el apoyo del Programa de Excelencia Académica de la Coordinación de Perfeccionamiento del Personal de Educación Superior (Proex-Capes 364/2021), en el contexto del Programa de Posgrado en Enfermería de la Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brasil. Este artículo es derivado de la tesis doctoral titulada “Violência institucional à criança hospitalizada na perspectiva de acompanhantes e profissionais da saúde”, presentada al programa de posgrado en Enfermagem e Saúde de la Escola de Enfermagem de la Universidade Federal da Bahia.

3 Esta pesquisa foi financiada pela Universidade Federal da Bahia no âmbito do Programa da Pró-Reitoria de Assistência Estudantil (Proae 4/2018). Ainda, obteve-se apoio do Programa de Excelência Acadêmica da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Proex-Capes 364/2021), no contexto do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Enfermagem da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brasil. Artigo extraído da tese de doutorado intitulada “Violência institucional à criança hospitalizada na perspectiva de acompanhantes e profissionais da saúde”, apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Enfermagem e Saúde da Escola de Enfermagem da Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brasil, em 2021.

Theme: Promotion and prevention

Contribution to the discipline: This study offers significant contributions to Nursing teaching, research, management, and care, as identifying institutional violence against children in health services is fundamental to promoting safe, humanized, and good-quality care for them and their families. In addition, the article contributes to strengthening the advocacy practice within health services and helps fill a large gap in studies of this nature.

Received: February 09, 2022;

Sent to peers: 11/05/2022

Approved by peers: 16/02/2023

Accepted: February 28, 2023

To reference this article / Para citar este artigo / Para citar este artículo Santos ACPO, Piton TN, Camargo CL, Vargas MAO, Almeida LMJS, Dias MGPG. Institutional violence against hospitalized children: The perception of Nursing professionals. Aquichán. 2023;23(2):e2323. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2023.23.2.3

ABSTRACT

Objective: To understand the

perception of the Nursing team about institutional violence against

hospitalized children.

Materials and method: A qualitative,

descriptive and exploratory study, performed at a large-size public hospital in

Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, with 17 Nursing professionals working in the

Pediatrics unit, to whom semi-structured interviews were applied between March

and May 2019. The collected data were categorized in the NVIVO12 software and submitted for content analysis.

Results: The results are presented

in four categories: The professionals’ lack of knowledge about institutional

violence against hospitalized children; Recognition of institutional violence

related to problems in the hospital infrastructure, Recognition of

institutional violence in interpersonal relationships and Recognition of

institutional violence in the care practices.

Conclusions: It becomes necessary to

apply policies to confront institutional violence, ranging from training the

professionals to adapting the spaces and care practices to favor the children’s

hospitalization environment.

Keywords (Source: DeCS) Pediatric Nursing; child violence; Nursing care; in-hospital care; child

Objetivo: comprender la percepción del equipo de enfermería

acerca de la violencia institucional hacia el niño hospitalizado.

Materiales y método: estudio cualitativo, descriptivo y exploratorio,

realizado en hospital público de gran tamaño, en Salvador, Bahia, Brasil, a 17

profesionales de enfermería que actuaban en la unidad pediátrica, a quienes se

aplicó entrevista semiestructurada, entre marzo y mayo de 2019. Se recolectaron

los datos, los que se categorizaron en el software NVIVO12 y se sometieron a

análisis de contenido.

Resultados: se presentan los resultados en cuatro categorías

— el desconocimiento de los profesionales acerca de la violencia institucional

hacia el niño hospitalizado; el reconocimiento de la violencia institucional

relacionada a los problemas en la infraestructura hospitalaria; en las

relaciones interpersonales y en las prácticas de cuidado.

Conclusiones: es necesaria la aplicación de políticas para

hacer frente a la violencia institucional que van desde la capacitación de

profesionales hasta la adecuación de espacios y prácticas de cuidado como forma

de favorecer el entorno en que el niño se encuentra hospitalizado.

Palabras clave (Fuente: DeCS) Enfermería pediátrica; violencia infantil; cuidados en enfermería; asistencia hospitalaria; niñez

RESUMO

Objetivo: compreender a percepçao da equipe de enfermagem

sobre a violencia institucional contra a criança hospitalizada.

Materiais e método: estudo qualitativo, descritivo e exploratório,

realizado em hospital público de grande porte, em Salvador, Bahia, Brasil, com

17 profissionais de enfermagem que atuavam na unidade pediátrica, com os quais

foi aplicada entrevista semiestruturada, entre março e maio de 2019. Os dados

coletados foram categorizados no software NVIVO12 e submetidos a análise de

conteúdo.

Resultados: os resultados sao apresentados em quatro

categorias — o desconhecimento dos profissionais sobre violencia institucional

contra a criança hospitalizada; o reconhecimento da violencia institucional

relacionada aos problemas na infraestrutura hospitalar; nas relaçoes

interpessoais e nas práticas de cuidado.

Conclusões: faz-se necessária a aplicaçao de políticas para o

enfrentamento da violencia institucional que vao desde o treinamento de

profissionais até a adequaçao de espaços e práticas de cuidado como forma de

favorecer o ambiente em que a criança se encontra hospitalizada.

Palavras-chave (Fonte DeCS) Enfermagem pediátrica; violencia infantil; cuidados de enfermagem; assistencia hospitalar; criança

INTRODUCTION

Institutional Violence (IV) in health services is defined as the type that occurs within institutions, which is evident from care omissions to poor quality of the services due to the asymmetric power relations between users and professionals. In practice, this type of violence can be characterized by a lack of listening and time for the clientele, neglect, power abuse, and mistreatment resulting from prejudice and discrimination, denial of assistance, pilgrimage, violation of users’ rights, poor care quality, inaccurate diagnoses, disqualification of the life experience and medications to adapt the patient to the conditions of the service (1).

Several research studies that evidence the occurrence of harm in hospitalized children show that maltreatment occurs mainly as a result of abusive care practices, which compromises care and the quality of pediatric assistance (2, 3). However, although maltreatment is identified in health institutions, the professionals’ difficulty in recognizing it persists, which precludes the development of actions for coping with it (4, 5). In addition, this problem becomes worrisome when it is found in studies (6-9) that health professionals revealed that they lack sufficient knowledge about children’s rights in health services, which can make the pediatric hospital care environment conducive to IV situations.

Nursing professionals, as a profession that is directly related to the health care of individuals, need to know IV to identify it and, thus, ensure good quality care to children and families (10). Therefore, understanding the perception of the Nursing team regarding IV becomes relevant, as some surveys show that studies of this nature in pediatric environments are still scarce, although necessary to formulate coping policies and actions (1-4). Given these considerations, the objective of this study was to understand the perception of Nursing professionals about IV against hospitalized children.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

A qualitative, descriptive, and exploratory research study, developed as part of the Ph.D. thesis “Institutional Violence against Hospitalized Children from the Perspective of Companions and Health Professionals,” conducted from March to May 2019 at a large-size university public hospital in the city of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.

The research participants were nurses and nursing technicians who worked in the pediatric inpatient unit, with a capacity for 26 beds and who welcome children from 3 months to 14 years old for clinical and surgical treatment. The participants were intentionally selected by consulting the professionals’ schedules. The criterion for inclusion of the participants was to have more than two years of experience in pediatric hospital care (considering this as a minimum period to acquire experiences) and the exclusion criterion corresponded to being away (leave) from the service during data collection.

As a data collection technique, a semi-structured interview was used, with closed questions (for the participants’ sociodemographic profile) and open questions (to understand the participants’ perception of IV against hospitalized children). The guiding questions were the following: “Have you heard about IV?” and “What do you understand about that?” After the interviewees answered, an information folder was presented in which the definition of IV and its main characteristics were described. The interviewer then asked the following questions: Do you identify any type of IV against hospitalized children? and Which one(s)?.

The interviews were previously scheduled in a reserved place within the Pediatrics unit and conducted in person by a Scientific Initiation scholarship fellow and a Nursing undergraduate student, previously trained, under the supervision of a PhD student. The semi-structured script was previously tested (pilot) by the research team to identify if there was duplicity or distortions in the questions.

Data collection was described according to the consolidated criteria for qualitative research (COREQ (11) ). The interviews ended after data saturation, which occurred when the thematic content became repetitive. The interviews were recorded in an audio app on a mobile device and were later transcribed into a Word document. The interviews lasted a mean of 11 minutes. The maximum recording time was 34 minutes, with a minimum of 5. It is assumed that the variation in time was because the interviews were done in the workplace, which may have limited some participants’ testimonies.

The analytical procedures took place after an exhaustive reading of the interviews. For the analysis, the content analysis technique was used, which employs three execution poles: pre-analysis (floating reading, preparation, and organization of the material); exploration of the material (choice of analysis units and the material); and treatment of the results (elaboration of inferences and interpretation (12) ).

The interview data were read and validated by the research team, consisting of the researcher in charge and other researchers involved in the study. At that moment, the researcher triangulation strategy was chosen to allow several points of view to be discussed collectively, minimizing the risk of bias. Both data collection and analysis were guided by criteria and strategies to ensure rigor in qualitative research studies: Credibility —presented from the recording and transcription of the testimonies in full to data triangulation; Dependability —documentation of the entire conduction of the research, and Confirmability —review of the excerpts from the interviews conducted by peers (13). The data were grouped into categories within the NVIVO 12 qualitative analysis software, which enabled greater data exploration, word frequency measurement, and production of visual resources (12).

The research complied with the guidelines contained in the Declaration of Helsinki and in the Brazilian National Council of Ethics in Research (14). The right to the subjects’ secrecy, anonymity and privacy was ensured; therefore, the interviews continued with the presentation of the Free and Informed Consent Form, signed by the participants and the researcher. To ensure anonymity, the participants’ names were identified by professional category and by a number, which indicated the order of the interviews. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the study field under Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Appraisal No. 99681518.0.0000.5531.

RESULTS

The research participants were 17 Nursing professionals. According to the participants’ sociodemographic profile, it is noted that all interviewees were female, with a mean age of 40 years (from 27 to 60); black skin majority (99 %); 64 % with family incomes of up to five minimum wages, 23 % earning from 5 to 10 minimum wages and 11 %, from 10 to 20 minimum wages.

Regarding the professional category, 11 were nursing technicians (64.7 %) and 6 were nurses (35.3 %). Among the nursing technicians, 7 (46.66 %) had higher education, of which 1 (6.67 %) was a graduate with a specialization in Nursing; 4 (26.67 %) had an incomplete undergraduate degree in Nursing; 1 (6.67 %) had a bachelor’s degree and a specialization in Law, and 1 (6.67 %) had an incomplete undergraduate degree in the Administration area. Among the nurses, all had studied some specialization and 1 (6.67 %) had a master’s degree.

Regarding the time of experience in pediatric in-hospital care, the mean was 9 years (minimum of 3, maximum of 34) among the nursing technicians. The nurses had a mean time of experience in Pediatrics of 8 years (minimum of 2, maximum of 9).

The second part of the interview enabled us to understand the Nursing professionals’ perception of IV against hospitalized children. Thus, the results found were divided into four categories: a) Unawareness of IV against hospitalized children; b) Recognition of IV related to problems in the hospital infrastructure; c) Recognition of IV in interpersonal relationships, and d) Recognition of IV in the care practices.

It is important to highlight that the first category (“Unawareness of IV against hospitalized children”) was the most mentioned by the participants, which shows the lack of information about this type of violence among the Nursing professionals who worked in this pediatric hospital environment.

The “Recognition of IV related to problems in the hospital infrastructure,” “Recognition of IV in interpersonal relationships,” and “Recognition of IV in the care practices” categories were reproduced in the reports after the participants were informed about the definition and characteristics of IV contained in the folder.

Unawareness of IV Against Hospitalized Children

In this study, it was found that most of the Nursing professionals (86 %) were unaware or had limited knowledge about IV in the pediatric care environment, which can be confirmed in the reports below:

That’s all that happens to assault the patient inside the institution. (Nursing Technician 9)

I haven’t heard talking about this much, no. (Nurse 1)

Some professionals initially denied the existence of IV; however, when encouraged to talk about problems in the work environment, they made visible in their testimonies the presence of this type of violence in the pediatric care environment:

I haven’t identified institutional violence. I often notice that there was a failure in the system and some diseases that could have a treatment, even a cure, it’s made difficult because the child is left without care, when he/she’s not referred, or a late diagnosis, or was hospitalized in another institution and the doctor who examined him/her found that it was a simpler thing and did not investigate. (Nurse 1)

Here I don’t see it, I think the children are well-assisted. It’s proper assistance. As for the materials, some are missing, right? Some things are missing. (Nursing Technician 2)

Recognition of IV Related to Problems in the Hospital Infrastructure

In the second category, it was found that, after being informed about the definition and characteristics of IV, the participants related this type of violence to problems in the hospital infrastructure, caused by lack of materials, scrapping of devices and furniture, inadequacies in physical space and staff deficits. Such situations determined delays in procedures and exams, which exert a negative impact on health care, resulting in poor care quality.

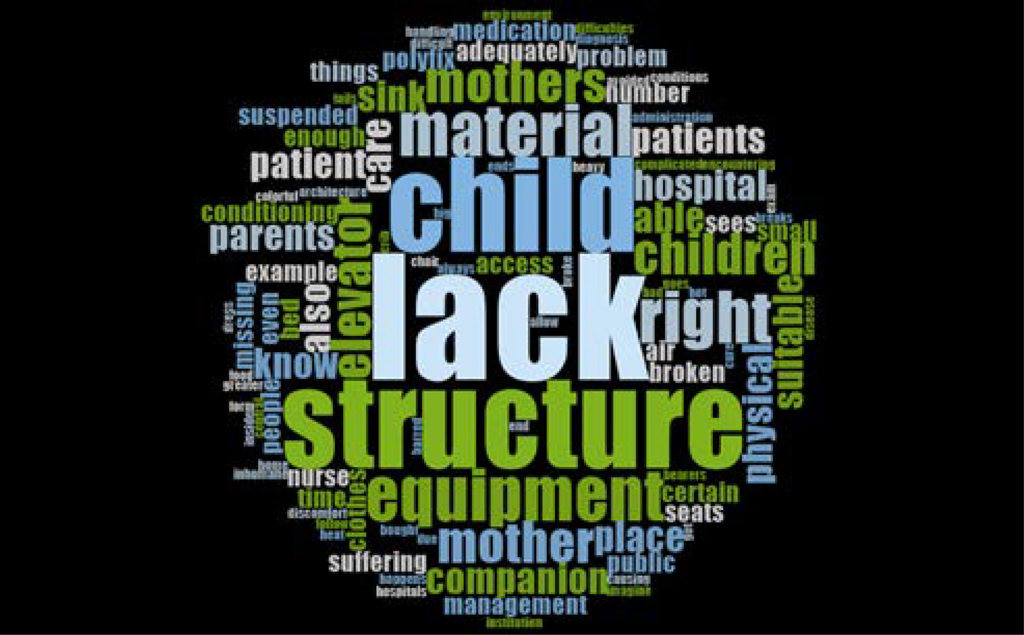

From the data contained in the interviews, Figure 1 was elaborated, which presents the word cloud generated by the NVIVO 12 software. It is noted that the words with greater prominence in the figure are the most frequent of this category, contained in the participants’ testimonies.

Figure 1 Perception of IV against Hospitalized Children Based on Infrastructure Problems. Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, 2022

Source: Prepared by the authors with the NVIVO 12 software

The reports below also present the Nursing professionals’ testimonies and describe the structure problems experienced by the children during their hospitalization:

Today you only have one stretcher-man during the weekends, you end up not taking exams those days. (Nurse 1)

Specific polyfix for children is missing, sometimes there’s only adult polyfix, which is heavy. In a child with central access, the adult polyfix may pull and lose the access. We work with what we have and sometimes we don’t have the right materials. (Nursing Technician 6)

The lack of working devices hinders our work and the care we give to the patients, the children and the families. (Nursing Technician 11)

Recognition of IV in Interpersonal Relationships

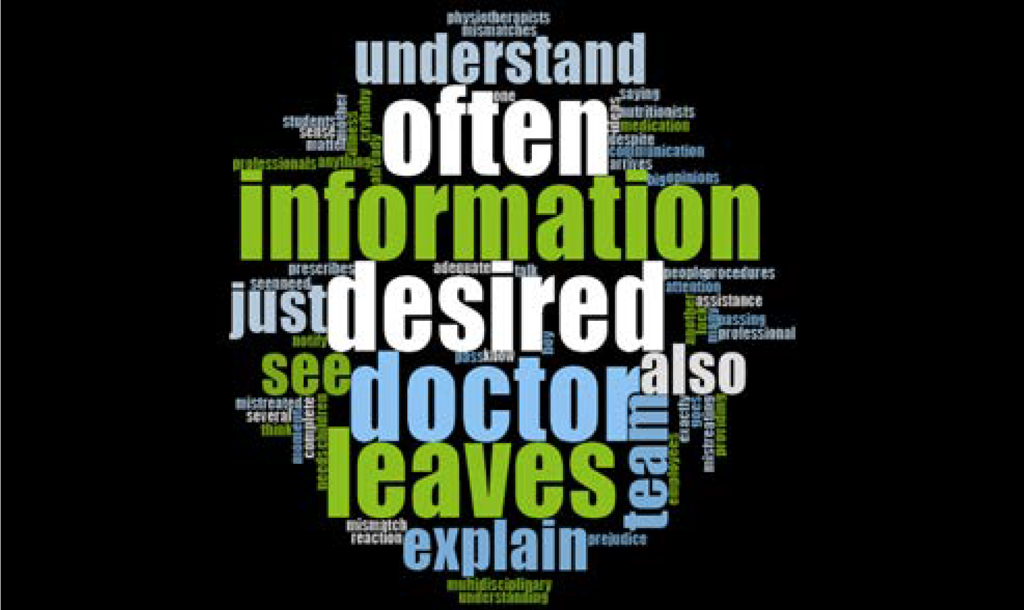

In the third category, situations in which professionals perceived IV from the problems in the relationships between professionals, children and families, characterized by lack of communication, inattention and discrimination were described. Figure 2 shows the word cloud, where the words with greater prominence are the most frequent in the excerpts of this category.

Figure 2 Perception of IV against Hospitalized Children from Interpersonal Relationship Problems. Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, 2022

Source: Prepared by the authors with the NVIVO 12 software

The excerpts below confirm the perception of IV in the relationships between professionals, children and families.

There’s no clear conversation with the children. Sometimes we think children don’t understand, but they understand everything. (Nurse 5)

Acting with prejudice, when the professional says: “Ah, what a crying boy, such a big boy!” Many times we think that children have to be here and already understand everything they have to go through. (Nursing technician 8)

Many times, children are seen as if they’re not going to understand anything, that there is no need to talk to them. There are professionals who say that this is nonsense and that it is to do what has to be done, because of time and issues inherent to hospital dynamics. (Nurse 4)

Recognition of IV in the Care Practices

In the fourth category, the health professionals also understood IV based on problems related to the care practice, evidenced by multiple manipulations, imprecise diagnoses, imposition of norms and routines of the service and omissions, as can be identified in the reports presented below:

Maybe the routines also harm these children a little, no matter how hard we try to adapt, sometimes we can’t do it in a way that is better for them. (Nurse 4)

If his/her diagnosis came out well earlier, he/she [the patient] wouldn’t have gone through so much that he/she went through, he/she got really worse, a long time in the hospital. (Nurse 2)

It’s you not providing adequate assistance to the patient. For example, I can see that patient has an infiltrated access, I saw that infiltrated access and pretended I didn’t see it, then the boy’s arm starts to swell, because I think I shouldn’t get the access, because it’s the end of the shift. (Nursing technician 1)

DISCUSSION

The Nursing professionals’ reports revealed that most of them are still unaware of IV or misunderstand its concept. This fact is confirmed by other research findings that have shown that, over the years, IV in health services has been discussed in a basic and fragmented way, due to a scarcity of information, scientific studies and discussions in this regard, which hinders its real understanding and negatively affects the engagement of managers and health professionals alike (1-4).

Regarding the approach to IV in health by the United Nations and the World Health Organization, it is important to note that it has been discussed to a limited extent in such agendas, which further limits the mobilization of resources in actions related to monitoring and its coping. In addition to that, most of the studies related to child protection in health services proposed by several countries have focused on identifying and acting on the notification of cases of violence that reach such institutions; however, it appears that there is still a large gap in studies on violence in or by health services (5,15-18).

Similarly, in Brazil, IV has also been approached incipiently. Data from the report by the Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights in 2021 disclosed the record of 8,500 complaints of infringements committed in health institutions; although relevant, this data does not detail how the practice of IV has been taking place in these services (19).

Also in Brazil, some studies prove that, although IV exists in the most varied forms within hospitals, the lack of knowledge of those involved (professionals and users) allows attitudes of abuse of authority to be produced and understood as necessary to provide health care (20, 21). Attitudes of disrespect and power abuse were also described in a survey carried out in public health services in Brazil, revealing that violence in the services’ routine is consented to by the users cared for and silenced by Nursing professionals (22).

It is important to highlight that, by denying or silencing IV in health services, the professionals may be inhibited from revealing the embarrassing content of this practice; therefore, it is possible Nursing professionals are still afraid to acknowledge the presence of IV in their work environments in front of a health team and of the user (22). Therefore, there is a need for investments in training and engagement of health teams to monitor and deal with the violence practiced in health services (23).

Regarding the characteristics of the infringements committed by the Nursing team in pediatric inpatient units, several studies confirm that they take place through conflicts, aggression and neglect (2, 3). Other research studies in Transylvania and Italy confirm the existence of other types of infringements and reveal that hospitalized children do not have their rights fully guaranteed during the hospitalization period. The main violations cited were treatments based on obsolete medical practice principles, disrespect for the rights of agreement or disagreement in their treatment and disrespect for the right to continue school monitoring, as well as the right not to feel pain (7, 8).

In this study, when recognizing IV situations in the pediatric care environment, Nursing professionals confirmed that they were mainly related to infrastructure problems such as lack of materials, problems in physical structure, staff deficits, and scrapping of devices. The evidence of this problem and the recognition of IV in the hospital environment in the participants’ reports indicate that they perceive it predominantly in its structural form.

A similar perception to the findings of this study was detected in a research study that interviewed professionals and managers, where both understood structural violence as the main type of IV found in health services (22). The presence of structural violence in health services has been highlighted in research studies, confirming its existence in institutions and its relationship with service precariousness (1, 20, 22, 24).

In the third category, situations were described where the Nursing professionals perceived IV from the problems in the relationships between professionals, children and families, characterized by lack of communication, inattention and discrimination. Lack of communication can mask a problem intensely rooted in the health professionals’ paternalistic attitudes, which results in the loss of users’ autonomy. This situation infringes patients’ dignity and well-being, in addition to clearly and explicitly constituting the asymmetric power relations present in the IV theoretical framework (25, 26).

Therefore, it is important to highlight the need for the Nursing team to inform children about procedures and exams to respect their autonomy, as such interventions cause them pain, leaving them sad and anxious (10). In this sense, it is worth reflecting on and proposing strategies so children and families become active subjects of the care process through clear communication, according to the needs and specificities of their age group, diagnosis, physical condition, and cognitive ability (25- 28).

The problems related to the care practices, the last category described by the Nursing professionals, resulted from their difficulty dealing with ethical issues involving the autonomy and consent of the children and families. The problems pointed out by the participants were as follows: multiple manipulations, imposition of norms and routines, and omissions.

The situations involving multiple manipulations and the imposition of norms and routines reflect the influence of the model centered on medical professionals, based on body control and discipline as something fundamental for the treatment of hospitalized individuals (21). Thus, the body is considered an object of power, which is available to the professionals. Therefore, in this conception, the routine is established by obedience, passivity and silence, without respecting the uniqueness of each patient and family (20).

According to Foucault, this conception originated in the eighteenth century, when he glimpsed the scientific bases of Medicine, which structures its actions from the perspective of the body and disease. Thus, the body of the individual becomes an object of domination, as well as the various forms of medical knowledge constitute positive notions of health and normality, in which the definition of the model man is described as a non-sick man (29).

Some research studies corroborate this finding, assuming that IV is also much more linked to the unrestricted disciplinary issue of norms, technology management, bureaucracy and work routines than merely to subjective, personal or relational aspects (30, 31). Likewise, the overvaluation of hospital norms, routines, and procedures makes individuals perceive the hospital as a space marked by enclosure and confinement (30- 32). Overvaluing norms and routines, as in the cases of carrying out procedures at restricted times, result in situations of discomfort and child agitation (30,31). In the long term, these adverse situations experienced in childhood can produce psychological distress and disorders (33).

In this study, despite care omissions, the participants perceived its relationship to the problems of work overload and the reduced number of professionals. Care omissions were also found in other studies conducted in Germany and Nepal, which confirm the presence of this type of violence in general, in pediatric, psychiatric and neonatal care units alike (2, 3, 34).

Regarding the propositional actions to cope with IV in pediatric care hospital environments, many studies show the need for training professionals and managers to develop a peace culture and a health advocacy practice (35, 36).

It was noted that this research obtained restricted representativeness, considering that it was performed in a single hospital in northeastern Brazil, which is a limitation of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, it was possible to understand that Nursing professionals are unaware of IV and that, when perceiving it, they recognize it from the problems related to hospital structure, interpersonal relationships and adverse situations in the care practices.

To cope with IV, it becomes necessary to apply policies that range from training professionals to expand the knowledge about this theme to adapting physical spaces and care practices to favor the children’s hospitalization environment. In addition, it is fundamental to reflect on the care practices and the working conditions and, above all, the promotion of a culture of peace and protection of children’s rights in health services should be encouraged.

Conflict of interest: none declared

REFERENCES

1. Santos ACPO, Camargo CL, Vargas MAO. Hospital structure elements demarcating (in)visibilities of institutional violence against children. Rev Bras Enferm. 2022; 14;75(supl. 2):e20200785. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0785

2. Clemens V, Hoffmann U, König E, Sachser C, Brähler E, Fegert JM. Child maltreatment by nursing staff and caregivers in German institutions: A population-representative analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;95:104046. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104046

3. Hoffmann U, Clemens V, König E, Brähler E, Fegert JM. Violence against children and adolescents by nursing staff: Prevalence rates and implications for practice. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14(1):43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00350-6

4. Finch M, Featherston R, Chakraborty S, Bjørndal L, Mildon R, Albers B et al. Interventions that address institutional child maltreatment: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst Rev. 2021;17:e1139. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1139

5. Alfandari R, Taylor BJ. Processes of multiprofessional child protection decision making in hospital settings: Systematic narrative review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021:295-312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211029404

6. Rosa CN, Santos ACPO, Camargo CL, Vargas MAO, Whitaker MCO, Araujo CNV et al. Direitos da criança hospitalizada: percepção da equipe de enfermagem. Enferm Foco. 2021;12(2):24449. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21675/2357-707X.2021.v12.n2.3853

7. Albert-Lõrincz C. The situation of pediatric patients’ rights in the Transylvanian healthcare. Orv Hetil. 2018;159(11):423-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1556/650.2018.30999

8. Bisogni S, Aringhieri C, McGreevy K, Olivini N, Lopez JRG, Ciofi D et al. Actual implementation of sick children’s rights in Italian pediatric units: a descriptive study based on nurses’ perceptions. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0021-0

9. Neutzling BRS, Tomaschewski-Barlem JG, Barlem ELD, Hirsch CD, Pereira LA, Schallenberguer CD. Em defesa dos direitos da criança no ambiente hospitalar: o exercício da advocacia em saúde pelos enfermeiros. Esc. Anna Nery. 2017;21(1):e20170025. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5935/1414-8145.20170025

10. Comparcini D, Simonetti V, Tomietto M, Leino-Kilpi H, Pelander T, Cicolini G. Children’s perceptions about the quality of pediatric nursing care: A large multicenter cross-sectional study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2018;50(3):287-95. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12381

11. Souza VRS, Marziale MHP, Silva GTR, Nascimento PL. Tradução e validação para a língua portuguesa e avaliação do guia COREQ. Acta Paul enferm. 2021;34:eAPE02631. DOI: https://doi.org/10.37689/acta-ape/2021AO02631

12. Lima JLO, Manini MP. Metodologia para análise de conteúdo qualitativa integrada à técnica de mapas mentais com o uso dos softwares NVIVO e FREEMIND. Inf. Inf. 2016;21(3):63-100. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5433/1981-8920.2016v21n3p63

13. Holanda GS, Farias IMS. Estratégia da triangulação: uma incursão conceitual. Revista Atos de Pesquisa em Educação. 2020;15(4):1150-66. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7867/1809-0354.2020v15n4p1150-1166

14. Brasil. Resolução 466/12, de 12 de dezembro de 2012, Dispõe sobre pesquisa envolvendo seres humanos. [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2012. Disponível em: http://goo.gl/joVV2Q

15. Cappa C, Petrowski N. Thirty years after the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child: Progress and challenges in building statistical evidence on violence against children. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt. 1):104460. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104460

16. M’jid NM. Global status of violence against children and how implementation of SDGs must consider this issue. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt. 1):104682. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104682

17. Vaghri Z, Samms-Vaughan M. Accountability in protection of children against violence: Monitoring and measurement. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt. 1):104655. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104655

18. Fortson BL, Klevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, Alexander SP. Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. [Internet]. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38864

19. Brasil. Ministério da Mulher, da Família e dos Direitos Humanos. Painel de dados da ouvidoria nacional de direitos humanos [Internet]. Brasília: Ministério da Mulher, da Família e dos Direitos Humanos; 2021. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/mdh/pt-br/ondh/paineldedadosdaondh/copy_of_dados-atuais-2021

20. Oliveira VJ, Penna CMM. O discurso da violência obstétrica na voz das mulheres e dos profissionais de saúde. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2017;26(2):1-10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072017006500015

21. Santos ACPO, Camargo CL, Vargas MAO, Araújo CNV, Conceição MM, Zilli F. Violência institucional hospitalar na prática de cuidado à criança: análise do discurso na perspectiva foucaultiana. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2022;31:e20220002. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-265x-tce-2022-0002pt

22. Moreira GAR, Vieira LJES, Cavalcanti LF. Manifestações de violência institucional no contexto da atenção em saúde às mulheres em situação de violência sexual. Saúde Soc. 2020;29(1):e180895. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S010412902020180895

23. Hansen J, Terreros A, Sherman A, Donaldson A, Anderst J. A system-wide hospital child maltreatment patient safety program. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):e2021050555. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-050555

24. Tickell KD, Mangale DI, Tornberg-Belanger SN, Bourdon C, Thitiri J, Timbwa M et al. A mixed method multi-country assessment of barriers to implementing pediatric inpatient care guidelines. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0212395. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212395

25. Pūras D. Human rights and the practice of medicine. Public Health Rev. 2017;38(9). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0054-7

26. Santos ACPO, Camargo CL, Vargas MAO, Conceição MM, Whitaker MCO, Maciel RCM, Baptista SCO, Santo MRE. Perception of family members and health professionals about institutional violence against hospitalized children. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2022;43:e20210244. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2022.20210244.en

27. Lee SP, Haycock-Stuart E, Tisdall K. Participation in communication and decisions with regards to nursing care: The role of children. Enferm Clin. 2019;29(2):715-19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.04.109

28. Kruszecka-Krówka A, Smoleń E, Cepuch G, Piskorz-Ogórek K, Perek M, Gniadek A. Determinants of parental satisfaction with nursing care in paediatric wards-a preliminary report. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1774. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101774

29. Foucault M. Microfísica do poder. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Graal; 2001.

30. Reyes MA, Etinger V, Hall M, Salyakina D, Wang W, Garcia L et al. Impact of the Choosing Wisely® campaign recommendations for hospitalized children on clinical practice: Trends from 2008 to 2017. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(2):68-74. DOI: https://doi. org/10.12788/jhm.3291

31. Levinson W, Born K, Wolfson D. Choosing Wisely Campaigns: A work in progress. JAMA. 2018;319(19):1975-976. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2202

32. Foucault M. Vigiar e punir: História da violência nas prisões. 27ª ed. Petrópolis: Vozes; 1987.

33. Sampath R, Nayak R, Gladston S, Ebenezer K, Mudd SS, Peck J et al. Sleep disturbance and psychological distress among hospitalized children in India: Parental perceptions on pediatric inpatient experiences. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2022;27(1):e12361. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12361

34. Kc A, Singh DR, Upadhyaya MK, Budhathoki SS, Gurung A, Målqvist M. Quality of care for maternal and newborn health in health facilities in Nepal. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(supl. 1):31-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02846-w

35. Santos AC, Vargas MA, Camargo CL, Forte EC, Nepomuceno CM, Ventura CA. Desafios para o exercício da advocacia em saúde à criança hospitalizada durante a pandemia COVID-19. Acta Paul Enferm. 2023;36:eAPE009931. DOI: https://doi.org/10.37689/acta-ape/2023AO009931

36. Abbasinia M, Ahmadi F, Kazemnejad A. Patient advocacy in nursing: A concept analysis. Nurs Ethics. 2020; 27(1):141-51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019832950