|

Article

Jack Roberto Silva Fhon1

Vilanice Alves de Araújo Püschel2

Larissa Bertacchini de Oliveira3

Jessica Soares Silva4

Rodrigo Santana Tolentino5

Vinicius Cardoso da Silva6

Luipa Michele Silva7

Fábio da Costa Carbogim8

1 ![]() 0000-0002-1880-4379 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. betofhon@usp.br

0000-0002-1880-4379 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. betofhon@usp.br

2 ![]() 0000-0001-6375-3876 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. vilanice@usp.br

0000-0001-6375-3876 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. vilanice@usp.br

3 ![]() 0000-0001-9509-4422 Universidade de São Paulo/Instituto do Coração, Brazil. larissa.oliveira@hc.fm.usp.br

0000-0001-9509-4422 Universidade de São Paulo/Instituto do Coração, Brazil. larissa.oliveira@hc.fm.usp.br

4 ![]() 0000-0003-0699-968X Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. jessica.soares@hc.fm.usp.br

0000-0003-0699-968X Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. jessica.soares@hc.fm.usp.br

5 ![]() 0000-0002-4400-4690 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. rodrigo.tolentino@hc.fm.usp.br

0000-0002-4400-4690 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. rodrigo.tolentino@hc.fm.usp.br

6 ![]() 0000-0001-8198-4539 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. vinicius.cardoso.silva@usp.br

0000-0001-8198-4539 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. vinicius.cardoso.silva@usp.br

7 ![]() 0000-0001-6147-9164 Universidade Federal de Catalão, Brazil. luipams@ufcat.edu.br

0000-0001-6147-9164 Universidade Federal de Catalão, Brazil. luipams@ufcat.edu.br

8 ![]() 0000-0003-2065-5998 Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Brazil. fabio.carbogim@ufjf.br

0000-0003-2065-5998 Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Brazil. fabio.carbogim@ufjf.br

Received:

21/04/2022

Sent to peers:

09/06/2022

Approved by peers:

03/10/2022

Accepted: 19/10/2022

Theme: Care processes and practices

Contribution to the subject: This article contributes to the knowledge of how nurses have felt and experienced providing care to patients with COVID-19, considering their limited preparation to face the pandemic and the fears that emerged during this entire process. In addition, this article highlights the importance of the continuous care process and the nursing practice itself, organized to provide care to this population.

Para citar este artículo / To reference this article / Para citar este artigo: Fhon JRS, Püschel VAA, Oliveira LB, Silva JS, Tolentino RS, Silva VC, Silva LM, Carbogim FC. The lived experiences of nursing professionals providing care to COVID-19 patients. Aquichan. 2022;22(4):e2247. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2022.22.4.7

Abstract

Objective: To analyze nursing professionals’ reports on their lived experience in the care provided to

hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Materials and

Methods: This is an exploratory study using a qualitative analysis, which included

twelve nurses and eight nursing technicians from a public hospital in Brazil,

conducted between December 2020 and February 2021. The inclusion criteria were

professionals who provided care to COVID-19 patients in emergency, intensive

care, and inpatient units and who had at least one year of experience in the

institution. The interviews were analyzed through content and similarity

analysis that generated a similarity tree; the Reinert method was used for thematic categories.

Results: Most participants

were female, with a mean age of 34.15 years and 4.85 years of experience. From

the analysis, the words ‘patient,’ ‘to stay,’ and ‘to find’ were the most

frequent, and for the categories, they were “nursing professionals’ feelings

regarding the pandemic,” “the nurses’ role and work with the multi-professional

team in the care provided to patients with COVID-19,” “precautions with the

care provided to patients with COVID-19,” and “nursing professionals’ concern

that their family members may become ill during the pandemic.”

Conclusions: The nursing staff

is predominantly composed of females and, in their reports on the lived

experience of providing care to patients with COVID-19, they pointed out that

concern and fear were prevalent, with the family being one of the protective

factors to withstand the risks of working against something novel that may

result in death.

Keywords (Source DeCS): Coronavirus infections; COVID-19; Nursing; pandemics; life change events; qualitative research.

Resumen

Objetivo: analizar los

relatos de profesionales de enfermería sobre la experiencia y vivencia en la

asistencia brindada a los pacientes hospitalizados con covid-19.

Materiales y método: estudio exploratorio, con análisis cualitativo, en el que participaron

12 enfermeros y ocho técnicos de enfermería de un hospital público en Brasil,

realizado entre diciembre de 2020 y febrero de 2021. Como criterio de inclusión

estaban profesionales que brindaban asistencia a pacientes con covid-19, en

unidades de emergencia, de terapia intensiva y de hospitalización y al menos un

año de experiencia en la institución. El análisis de las entrevistas por el

análisis de contenido y por el análisis de similitud que generó un árbol de

similitud y se utilizó el método Reinert para las

categorías temáticas.

Resultados: la mayoría de los participantes fue mujer, con promedio de 34,15 años y

experiencia de 4,85 años. De los análisis, las palabras “paciente”, “ficar” (“quedar”) y “achar”

(“crer”) fueron las más frecuentes y las categorías

“sentimientos de los profesionales de enfermería ante la pandemia”; “rol del

enfermero y trabajo con el equipo multiprofesional en

los cuidados al paciente con covid-19”; “cuidados en la atención al paciente

con covid-19” y “preocupación de los profesionales de enfermería de que sus

familiares se enfermaran durante la pandemia”.

Conclusiones: la enfermería es predominantemente constituida por mujeres y, en sus

relatos sobre la experiencia y vivencia de cuidar a paciente con covid-19,

señalaron que la preocupación y el miedo fueron predominantes, siendo la

familia un de los factores protectores para soportar

los riesgos de trabajar en contra algo nuevo y que puede culminar con la

muerte.

Palabras clave (Fuente DeCS): Infección por coronavirus; covid-19; enfermería; pandemia; acontecimientos que cambian la vida; investigación cualitativa.

Resumo

Objetivo: analisar os

relatos de profissionais de enfermagem sobre a experiência e vivência na

assistência prestada aos pacientes hospitalizados com covid-19.

Materiais e método: estudo exploratório, com análise qualitativa, do qual participaram 12

enfermeiros e oito técnicos de enfermagem de um hospital público no Brasil,

realizado entre dezembro de 2020 e fevereiro de 2021. Como critério de inclusão

estavam profissionais que prestavam assistência a pacientes com covid-19, em

unidades de emergência, de terapia intensiva e de internação e pelo menos um

ano de experiência na instituição. A análise das entrevistas pela análise de

conteúdo e pela análise de similitude que gerou uma árvore de similitude e foi

utilizado o método Reinert para as categorias temáticas.

Resultados: a maioria dos participantes foi mulher, com média de 34,15 anos e

experiência de 4,85 anos. Das análises, as palavras “paciente”, “ficar” e “achar”

foram as mais frequentes e as categorias “sentimentos dos profissionais de

enfermagem ante a pandemia”; “papel do enfermeiro e trabalho com a equipe

multiprofissional nos cuidados ao paciente com covid-19”; “cuidados no

atendimento ao paciente com covid-19” e “preocupação dos profissionais de

enfermagem de seus familiares adoecerem durante a pandemia”.

Conclusões: a enfermagem é predominantemente constituída por mulheres e, nos seus

relatos sobre a experiência e a vivência de cuidar de paciente com covid-19,

apontaram que a preocupação e o medo foram predominantes, sendo a família um

dos fatores protetores para suportar os riscos de trabalhar contra algo novo e

que pode culminar com a morte.

Palavras-chave (Fonte DeCS): Infecções por coronavírus; covid-19; enfermagem; pandemias; acontecimentos que mudam a vida; pesquisa qualitativa.

Introduction

The pandemic caused by the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11th, 2020, has been a challenge for all countries due to the severe health, economic, and social crisis (1). Of epidemiological importance, by February 11th, 2022, a total of 406,809,841 cases and 5,794,030 deaths have been confirmed worldwide. In Brazil, a total of 27,135,550 cases and 636,338 deaths had been confirmed (2).

Nursing teams have been working on the front lines as responders to the pandemic since its inception, providing care to COVID-19 patients daily, being exposed to contamination by the disease, as well as to the development of psychological changes due to the pressure suffered inside and outside healthcare organizations (3).

The pandemic had a profound impact on nursing professionals due to the complexity of providing care to a novel and unknown disease, raising questions concerning nursing practices, the need to search for scientific evidence, and the need to promote continuous education and research (4).

A study conducted in the UK highlighted nursing professionals found new ways of working, such as starting to work remotely, but were faced with infection/control risks and the impact on users during the pandemic. In addition, the need for support became evident for nursing professionals who provided care during the pandemic as they suffered mental health impacts manifested as anxiety, stress, panic, and communication issues (5). Still, it is emphasized that the risk of infection and performance limitation is higher due to work overload (6).

A Brazilian study conducted with nurses who provided care to Covid-19 patients in intensive care units (ICU) showed that these professionals had to live with “situations that interfered with their physical and mental health, involving the fear of contamination, the severity of the patients’ conditions, the experience of witnessing co-workers become ill, and distancing from family members and patients” (7: 7).

With the aim of understanding the nursing staff’s experience at a public teaching hospital, which specializes in cardiology and is a reference hospital in Brazil and Latin America that started providing care to Covid-19 patients, this study was developed to answer the following question: how have nursing professionals experienced the care provided to hospitalized COVID-19 patients in a public teaching hospital in São Paulo? Thus, this study aimed to analyze the reports of nursing professionals concerning their lived experiences in the care provided to hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Materials and Methods

This is an exploratory study, which used qualitative analysis, carried out in a public teaching hospital that provides high complexity care to patients in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. The manuscript was conducted according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ [8]).

The study was carried out at the Instituto do Coração (InCor), Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo-SP, Brazil, which, along with other institutes within the hospital complex, has been providing care to patients infected by Sars-CoV-2. At InCor, there are 535 beds distributed among 13 care units; 168 belong to the highly complex ICUs. During the pandemic, 100 beds, including emergency, intensive care, and inpatient unit beds, were allocated for the care of COVID-19 patients.

The study was conducted with nurses and nursing technicians providing care to patients hospitalized for COVID-19, who were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: professionals who provided care to COVID-19 patients in emergency, intensive care, and inpatient units and had at least one year of experience in the institution. Professionals who were on vacation or leave due to health problems were excluded.

The first contact with the nursing professionals was carried out by phone; they were invited to participate in the study. The informed consent form (ICF) was sent virtually, and a meeting time was scheduled for the interview.

To comply with social distancing, the interviews were conducted in a remote format through the Google Meet platform. The interviews were carried out from December 2020 to February 2021, had an average duration of 40 minutes, were recorded with the participant’s permission, and stored for later transcription and analysis.

For data collection, an instrument composed of two parts was used. The first part was comprised of sociodemographic data such as sex, age, religion, profession, education level, and time working in the institution. The second part was composed of the following guiding questions: “tell us about your lived experience providing care to COVID-19 patients”; “what has it been like for you to provide care to COVID-19 patients (confirmed or suspected)?”; “describe how you feel when providing care to COVID-19 patients”; “what feelings did you experience or have you experienced?; have there been changes in your work routine following the COVID-19 pandemic? If so, tell me about it”; “has the COVID-19 pandemic interfered with your personal and family life? If so, tell me about it”; “how do you evaluate this moment for nursing?”; what is the role of nursing during this pandemic?”; “what was the greatest experience or lesson to be learned when experiencing care during the pandemic?”, and “what was it like to provide care to a well-known colleague admitted to the ICU?”.

The interviews were recorded and transcribed in full by the interviewer, and the content was validated by the study coordination. During the validation process, some terms used by the professionals were standardized, respecting the participants’ speech and context, aiming to simplify the comparison during the analysis.

The interviews were organized in a database and analyzed using the Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (IRAMUTEQ) 0.6 alpha 3 software, Brazilian version (9), with the use of the lexometric content analysis technique, as it is able to verify the frequency of word usage in a given text (10). The established themes were interpreted in light of the theoretical referential on COVID-19, occupational health, and the role of nurses on the front line, grounded on several authors (3-7).

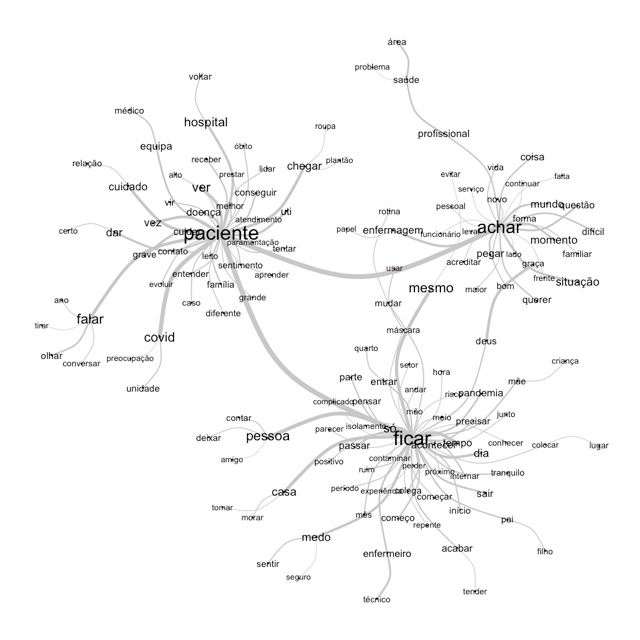

Similarity analysis was also used, which is based on graph theory, allowing the identification of uses between words and the relationship between them, shaping the structure of the text corpus. The figure formed was the maximum tree, where the ‘nodes’ can be identified based on the words with the highest frequencies. The creation of the figure had a frequency greater than 40 (9).

Furthermore, the text was submitted to the Reinert method, which presents a descending hierarchical classification of the uses of terms in a specific segment with the objective of identifying co-occurrences of terms in the same segments, distributing texts in classes by proximity, and hierarchizing the relative presence of each term in the word classes created. Through the software, it was possible to create the dendrogram, which displays the categories formed by grouping the words similar to each other. The categories are exemplified by the participants’ statements (P), according to the order in which the interview was conducted (from 1 to 20).

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Nursing School of the Universidade de São Paulo (Legal Opinion 4,072,114) and by the Ethics Committee for Research Project Analysis of the Hospital das Clínicas, the Medical School of the Universidade de São Paulo (Legal Opinion 4,249,921), in compliance with Resolution 466/2012 of the Conselho Nacional de Saúde, Brazil. The ICF was signed electronically.

Results

A total of twenty nursing professionals participated in the study, twelve of them were nurses, and eight were nursing technicians. Most were female (70 %), with a mean age of 34.15 years and a mean professional time of experience in the institution of 4.85 years.

Among the nurses, half had a lato sensu postgraduate qualification, and all had more than four years of experience in the profession working at InCor. The nursing technicians had a greater variety of experience in terms of time working in the profession and experience in the institution, ranging from 1 to 20 years.

The corpus composed of the 20 interviews was broken down into 1,169 text segments, which contained 63,493 uses, 2,893 analyzable forms, and 1,069 words that had a single use in the text, corresponding to 40.4% of the analyzable forms and 1.84% of the uses.

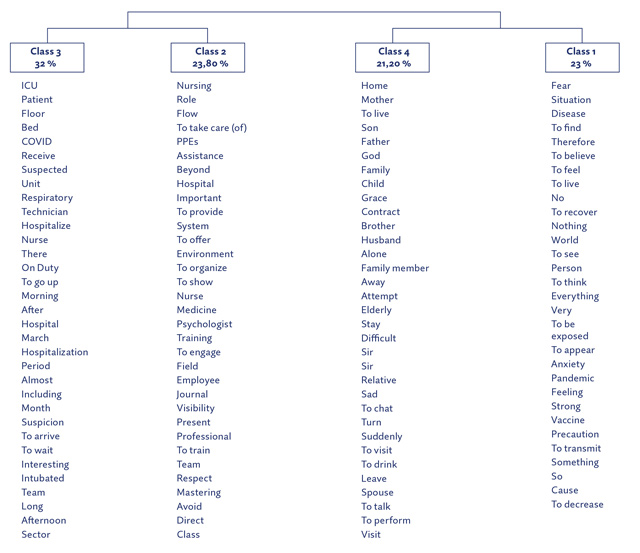

In the lexical analysis of the texts, a dendrogram was generated to display the classes formed by the 1,785 (88.1%) analyzable text segments (Figure 1). Thus, four classes emerged, which were categorized based on the theoretical framework, named as follows: “category 1 — nursing professionals’ feelings regarding the pandemic,” “category 2 — nursing professionals’ concern that their family members may become ill during the pandemic,” “category 3 — precautions with the care provided to patients with COVID-19,” and “category 4 — the nurses’ role and work with the multi-professional team in the care provided to patients with COVID-19.”

Figure 1. Dendrogram with the Categories Formed from the Synthesis of the Participants’ Statements. São Paulo, 2021 *

Source: IRAMUTEQ software.

The four thematic categories, along with some of the participants’, statements are presented below.

Category 1. Nursing Professionals’ Feelings Regarding the Pandemic

In this category, the feelings that emerged, such as the fear of getting sick, uncertainty, anxiety, and insecurity, during the care provided to COVID-19 patients were identified in the participants’ statements, with the appreciation of their own lives, according to the statements expressed below.

So, we need to prepare ourselves somehow. I think even to limit the contact with me because from now on I can be a source of contamination [...] I think it is a feeling of uncertainty, a feeling of doubt, of anxiety from that situation. (P1)

You feel fear, but, at the same time, you know that you have to face it head on, you have to fight, not give up at any moment [...] but I think that, in the beginning, it was much more difficult, only now I can face it differently. (P3)

I think that what I’ll take with me is learning to appreciate life itself. I think that this is a life experience because it’s not easy. I think I realized a lot of what goes through the minds of patients who are admitted to the ICU. (P9)

It’s the television, colleagues, public transportation… you were already experiencing this fear, and it intensified when you were there, face to face, with the virus, with the affected patients. (P12)

Category 2. The Nurses’ Role and Work with the Multi-Professional Team in the Care Provided to Patients with COVID-19

With the spread of the pandemic, nursing alongside the multi-professional team stood out for its work in the frontline providing care to COVID-19 patients, strengthening and acquiring new knowledge and teamwork during care, as evidenced in the following statements.

Nowadays, I’m more knowledgeable about it because we already know the contamination risks. We have all the equipment, so I’m safer when providing care. (P4)

So, the role of nursing is or was very important, both in raising awareness and in helping in the process of providing care to these patients so that the disease would not spread, that it would not contaminate more people, and for the cure itself. (P5)

The great learning is teamwork, getting everybody together to be able to offer the best because, like it or not, the multi-professional team, both the nursing technicians and the nurses, as well as the nurses, physicians, and physios [physical therapists], are part of patient care. (P20)

Category 3. Precautions with the Care Provided to Patients with COVID-19

With the onset of the pandemic, the work routine changed, and the care of COVID-19 patients led to increased demands on nursing care with longer hospital stays, where practices had to be adapted to reduce contamination.

These are patients that require prolonged hospitalization, and we have had patients staying with us for almost four months, so it is a long hospital stay, and we deal with all the complications resulting from this. (P1)

The first patients started to be admitted to the unit, and it was still a matter of the staff adapting to this new situation. So there was a lot of dressing up and also fear of what could happen to us, the professionals. (P19)

So, I had to learn a lot of things fast and at the same time. You could see patients developing complications quickly within a few days, 4 to 5 days, who needed to be intubated, and dialysis was turned on. Sometimes an IABP [intra-aortic balloon pump] was needed, along with cardiac support. (P20)

In addition to the change in work routines to provide care to COVID-19 patients, nursing professionals had to deal with the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), as the following statements demonstrate.

We managed everything, from difficult intubations with the entire risk of the team becoming contaminated; we were all dressed up. In the beginning, it was a little difficult to dress up [with] all the necessary material. I think that was a difficult part, the dressing up and the lack of materials. (P4)

As a nurse, I see that we are stagnating, of course. I see the COREN’s performance there trying their best, auditing to check if there is PPE available, which I think is the minimum that hospitals have to offer us. (P7)

Category 4. Nursing Professionals’ Concern that Their Family Members May Become Ill During the Pandemic

In this category, the statements of the nursing professionals are presented regarding their concern about contaminating their own family members with the novel coronavirus and the different measures followed to reduce this risk.

Shoes no longer get into the house, and basically my routine now is like this: it’s work-home, home-work without my family, my friends, or going out to parties. (P13)

In the beginning, there was a lot of talking, a lot of conversation, then we sort of isolated ourselves from the fake news, isolated ourselves from what was happening in the rest of the world, too, and to what was coming. (P14)

To synthesize the content, the existing relationship between the words that led to the maximum tree was analyzed. In it, it is possible seeing three nodes, namely: patient, to stay, and to find, as shown in Figure 2. The most referred words compose a tree with three nuclei and strong connections between them. The word ‘patient’ is in the first nucleus, the words ‘to stay’ are in the second, and the words ‘to find’ are in the third.

Figure 2. Maximum Tree Composed of the Interviews with

the Nursing Professionals Who Have Provided Care to Patients

with COVID-19. São Paulo, Brazil, 2021

Source: IRAMUTEQ software.

The nucleus composed of the word ‘paciente’ (‘patient’) is surrounded by words that highlight the ICU hospitalization process for COVID-19, the severity of the disease, the nursing professionals’ concern over patients —being isolated, not having contact with family members— in addition to aspects related to starting the shift/dressing up and the care itself, highlighting the relationship with the team and patients, the feelings generated, the interaction established through verbal (talking, conversation) and non-verbal communication (seeing), and having to address death. In this nucleus, there are verbs that stand out, such as ‘chegar’ (‘to arrive’), ‘falar’ (‘to talk’), ‘dar’ (‘to give’), ‘ver’ (‘to see’), ‘olhar’ (‘to look’), ‘conversar’ (‘to have a conversation’), ‘voltar’ (‘to return’), ‘prestar’ (‘to provide’), ‘lidar’ (‘to deal’), ‘receber’ (‘to receive’), ‘tentar’ (‘to try’), ‘aprender’ (‘to learn’), ‘entender’ (‘to understand’), ‘evoluir’ (‘to evolve’), and ‘conseguir’ (‘to achieve’).

The second node, which has as its nucleus the word ‘ficar’ (‘to stay’), is surrounded by words that highlight the nursing professionals’ concern with the isolated sick people and with contaminating their own family members, requiring them to leave home to stay isolated during the pandemic. Furthermore, nursing professionals felt fear and insecurity when providing care to patients diagnosed with COVID-19. The verbs that stood out the most in the ‘ficar’ (‘to stay’) nucleus were ‘passar’ (‘to spread’) (to the household), ‘contaminar’ (‘to contaminate’) (the team/feeling fear), ‘contar’ (‘to tell’), ‘internar’ (‘to hospitalize’), ‘entrar’ (‘to enter’) (the room), ‘sair’ (‘to leave’), ‘dispensar’ (‘to discharge’), ‘precisar’ (‘to need’), ‘conhecer’ (‘to know’), and ‘colocar no lugar’ (‘to set in place’).

The other node had as its main nucleus the word ‘achar’ (‘to find’) and is surrounded by words related to beliefs (‘Deus’, ‘graça’) [‘God’, ‘grace’], and worries (‘pegar’, ‘evitar’, ‘continuar’, ‘falta’) [‘to catch’, ‘to avoid’, ‘to continue’, ‘to lack’], in addition to situations desired by the professionals, such as having a moment with their families. It is also related to the need for new nursing professionals to provide continued care to COVID-19 patients. In this nucleus, the verbs that stood out the most were ‘pegar’ (‘to take’), ‘acreditar’ (‘to believe’), ‘querer’ (‘to want’), and ‘continuar’ (‘to continue’).

Discussion

The study participants were nursing professionals who had been working in the institution for more than four years and already had more experience when they started to provide care to people with a novel disease, namely COVID-19. Despite their experience in providing care, the daily difficulties faced by the professionals started emerging as they provided care to people with an unknown disease, leading to concern, fear, and caution to avoid their own contamination and that of their family members (6).

The nurses and nursing technicians who were on the frontline of providing care to COVID-19 patients lived through new experiences and feelings marked by fear and uncertainty, in addition to new challenges, meanings, and significance of being a nursing professional during a pandemic.

In this scenario, the illness and death of nursing professionals due to COVID-19 stand out, in addition to professional resignation. According to the Observatório de Enfermagem do Conselho Federal de Enfermagem (Nursing Observatory of the Federal Council of Nursing), since the onset of the pandemic, there have been 61,787 reported cases, 872 deaths, and a lethality rate of 2.46%, reported up to February 11, 2022 (11), although, as of April 2021, a drop in deaths has been observed (12). The International Council of Nurses (ICN) has recorded over 3,000 deaths of nurses worldwide, and in research conducted after one year of the pandemic, increased numbers of nurses quitting the profession were reported due to heavy workloads, insufficient resources, burnout, and stress as factors that are driving this exodus. The WHO has confirmed the mass trauma experienced by healthcare professionals, highlighted by the ICN in January 2021 (13).

Furthermore, in the face of instability in clinical cases and constant changes in the profile of patients admitted to hospital institutions, nursing professionals have emphasized the importance of social isolation and the adoption of non-pharmacological protective measures against COVID-19. An analysis of news stories in three Brazilian newspapers highlighted the importance of upholding protective measures against COVID-19 (14). In addition, Law 13,979/2020 highlights the importance of complying with social isolation and/or social distancing measures, compulsory testing, wearing masks, ventilating environments, washing hands, and using 70 % alcohol gel to fight coronavirus variants (15).

In the statements, the concerns and fear of personal and family contamination become evident, as well as the increase in demands related to hospitalized patients and the availability of human resources necessary for nursing care. Moreover, the professionals reported concern and fear for having experienced the illness of their colleagues since many of them got sick and had to receive care from professional colleagues. These aspects led to a variety of challenges related to mental health, especially burnout and fear, which deserve attention and support from hospital managers (16). In a study conducted with 120 nursing technicians in the first year of the pandemic, a prevalence of burnout syndrome was identified in 25.5% of the professionals (17). Another study conducted with nurses from 26 hospitals in Madrid found that professionals faced communication difficulties with managers (21.2 %), emotional exhaustion (53.5 %), and difficulty in expressing their emotions (44.9% (18)).

At the personal and family levels, there are concerns regarding contamination, getting sick, and contaminating family members. This leads to the adoption of measures of social distancing, especially from home, and to increase biosafety, such as wearing protective clothing when starting the shift and the use of masks. Regarding patients, the professionals expressed concern considering patients are isolated from their families, often in a serious condition, without contact with people who are close to them, which emphasizes the need for individualized care and a friendly conversation to externalize concerns and fears (18).

A study conducted with 437 healthcare professionals, with the objective of identifying the prevalence of suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19, showed that 36% of the participants reported presenting comorbidities, 21.1% had symptoms that suggested COVID-19, and 27 % had some type of test for the diagnosis of COVID-19 (16). The transmissibility potential of the disease is high, especially in healthcare settings, posing a real threat to nursing professionals, making them more susceptible to infection (19). These findings corroborate the present study’s data since, in the tree and the categories, the professionals’ concerns and worries regarding caring for themselves and their own family members emerged.

It is worth noting that, in the reports, the nursing care provided to people with COVID-19 demands increased workloads, especially when they are in a severe condition. These aspects are in line with the existing connections between the words ‘paciente’ (‘patient’), ‘COVID’, ‘grave’ (‘severe’), and ‘cuidado’ (‘care’). This indicates that contaminated patients require specialized care based on protocols that ensure the safety of professionals, but that, even following the routine, feelings such as fear, insecurity, and exposure of their families to contamination emerge, which have led several professionals to distance themselves from their homes. A study conducted in three Belgian hospitals aimed to evaluate the nurse-patient relationship required by COVID-19 patients and to identify the factors that influence nursing in this context (20). The study concluded that patients admitted to ICUs for COVID-19 require longer nursing care than other medical conditions, requiring an average ratio of one nurse for each patient.

In this sense, the pandemic increased the demand for professionals’ work to meet complex needs, generating work overload, exhaustion, and a high contamination risk for nursing professionals (21). In addition to the severity of the disease and the high technological apparatus required, especially in ICUs, which demand high workloads (22), the work in the pandemic setting has led professionals to experience physical exhaustion due to the long working hours and emotional fragility for experiencing severe cases that culminated on unexpected death, fear of their own contamination, and the risk of contaminating their family members with the virus (23).

The pandemic led nursing teams to face new challenges (24), such as fear, concern, and the need for new knowledge regarding an unknown and threatening disease, which led nursing professionals to become ill in addition to affecting the provision of continuous and comprehensive care to hospitalized patients and the risk of suffering psychological alterations, such as anxiety, depression, insomnia, and stress (25). A study carried out with 643 frontline nurses in hospitals in Wuhan, China, identified that one-third (33.4 %) of the participants reported that anxiety was associated with perceived stress, insomnia, frequency of night shifts per week, and level of fear of COVID-19 (26).

The pandemic also exposed the need for nursing teams to work based on technical and scientific competences, knowledge, skills, and emotional control over the practice, considering that providing care exposed the team to situations of risk, physical exhaustion, and negative emotional issues, responsibilities towards other people’s lives, in addition to facing fears and suffering (27).

When observing the maximum tree, another fact stands out in the study, the word ‘achar’ (‘to find’) has a connection with the word ‘paciente’ (‘patient’) and, around it, there are words such as ‘mundo’ (‘world’), ‘deus’ (‘god’), ‘familiar’ (‘family’), and ‘difícil’ (‘difficult’). These are words that highlight the situation lived by the professionals where they experienced difficult moments, which leads to the emergence of the spirituality dimension, with words related to beliefs, such as ‘Deus’ (‘God’), and ‘graça’ (‘grace’).

One of the potentials mentioned by healthcare professionals to provide continued patient care is to believe in a greater external power that, for some, may be God and, for others, means having a deep spirituality. Nursing professionals are constantly with their patients, including in the active dying process, and, in this pandemic, have experienced this process more intensely, losing patients who could not have family or friends present due to visiting restrictions. The special need for spiritual self-care was identified (28).

Spirituality can encompass values, beliefs, and religions, in addition to providing meaning to life, connection with others, and life purpose, being a transcendental or metaphysical phenomenon that correlates with the purpose and meaning of life (29). In nursing care, the dimension of spiritual health and self-care is supported by studies that emphasize the importance of the therapeutic dimensions of spirituality (30). A study carried out with 200 healthcare professionals in Malaysia identified that positive religious coping is vital in reducing anxiety and depression among healthcare professionals in the midst of a pandemic (31).

Furthermore, the multi-professional healthcare team has faced obstacles during the pandemic that negatively interfered with the work process, such as the absence of meetings and feedback, overlapping tasks, and work overload. However, it was strengthened by the knowledge exchange between different healthcare professionals in order to provide quality care (32).

As a study limitation, it is emphasized that this research was carried out in a single institution, which may have generated a bias in the answers due to all participants being in the same environment. However, it is considered that the findings express the experience of nurses and nursing technicians in patient care during a pandemic, which can contribute to new investments in the training of professionals and nursing education to face future situations.

The present study contributed to the understanding of the lived experiences of nursing professionals providing care to COVID-19 patients, the challenges faced by them, and the concerns and fears that emerged, in addition to highlighting the importance and centrality of this professional category during the pandemic.

In the nursing care provided, the work overload, the patient-centered care, the concern with the distance from the family, the fear of infection, and the emotional overload were evident. Moreover, the study raises aspects regarding nursing care to hospitalized COVID-19 patients, allows these professionals to speak out, and opens perspectives for research and interventions on aspects that can affect the quality of care and the physical and mental health of the professionals.

Conclusions

The lived experiences have different meanings for the professionals; while, for some, the COVID-19 pandemic brought fear, uncertainties, and concerns, for others, the distance from loved ones and being away from their families can led to fragilities in patient care. These behaviors can be products of the historical, social, and cultural processes that the pandemic carries in its genesis and can be internalized by society and professionals in a misguided way since there were several divergences in addressing and dealing with the virus.

In this study, it was found that the knowledge, behaviors, experiences, and feelings surrounding the care provided to hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a teaching hospital led to the emergence of four categories, namely: “nursing professionals’ feelings regarding the pandemic,” “the nurses’ role and work with the multi-professional team in the care provided to patients with COVID-19,” “precautions with the care provided to patients with COVID-19,” and “nursing professionals’ concern that their family members may become ill during the pandemic.”

Therefore, it is necessary to implement measures in all sectors of society, demystifying the experience that providing care to people with COVID-19 generates fear of contamination for not knowing the consequences, in addition to the fear of spreading the disease to loved ones, leading to the isolation of family members and friends.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

1. Oliveira WK, Duarte E, França GVA, Garcia LP. Como o Brasil pode deter a COVID-19. Epidemiol Serv Saude, 2020;29(2):e2020044. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742020000200023

2. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

3. Souza e Souza LPS, Souza AG. Enfermagem brasileira na linha de frente contra o novo Coronavírus: quem cuidará de quem cuida? J. nurs. health. 2020;10(n.esp.):e20104005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15210/jonah.v10i4.18444

4. Shun SC. COVID-19 pandemic: The challenges to the professional identity of nurses and nursing education. J Nurs Res. 2021;29(2):e138. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/JNR.0000000000000431

5. Foye U, Dalton- Locke C, Harju-Seppänen J Lane R, Beames L et al. How has COVID- 19 affected mental health nurses and the delivery of mental health nursing care in the UK? Results of a mixed-methods study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2021;28:126-37. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12745

6. Teixeira CFS, Soares CM, Souza EA, Lisboa ES, Pinto ICM, Andrade LR et al. A saúde dos profissionais de saúde no enfrentamento da pandemia de Covid-19. Ciênc. saúde coletiva, 2020;25(9). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020259.19562020

7. Conz CA, Braga VAS, Vasconcelos R, Machado FHRS, Jesus MCP, Merighi MAB. Experiences of intensive care unit nurses with COVID-19 patients. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2021;55:e20210194. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-220x-reeusp-2021-0194

8. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-57. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

9. Ratinaud P. IRaMuTeQ: Interface de R pour les analyses multidimensionnelles de textes et de questionnaires. [Internet]. 2020. Available from: http://www.iramuteq.org/

10. Bardin L. Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70; 2016.

11. Huang L, Lin G, Tang L, Yu L, Zhou Z. Special attention to nurses’ protection during the COVID-19 epidemic. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):10-2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2841-7

12. Conselho Federal de Enfermagem. Observatório de Enfermagem. Profissionais infectados com COVID-19 informado pelo serviço de saúde. [Internet] 2021. Disponível em: http://observatoriodaenfermagem.cofen.gov.br/

13. Conselho Federal de Enfermagem. Mortes entre profissionais de enfermagem por COVID-19 cai 71 em abril. [Internet] 2021. Disponível em: http://www.cofen.gov.br/mortes-entre-profissionais-de-enfermagem-por-covid-19-cai-71-em-abril_86775.html

14. Fhon JRS, Silva LM, Diniz-Rezende MA, Araujo JS, Matiello FB, Rodrigues RAP. Cuidado ao idoso durante a pandemia no Brasil: uma análise das matérias jornalísticas. Avances en Enfermería. 2021;39(1supl). DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/av.enferm.v39n1supl.90740

15. Brasil. Lei n.° 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020. [Internet] 2020. Disponível em: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/lei-n-13.979-de-6-de-fevereiro-de-2020-242078735

16. Hu D, Kong Y, Li W, Han Q, Zhang X, Zhu LX et al. Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine, 2020;24:100424. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424

17. Ribeiro BMSS, Scorsolini-Comin F, Souza SR. Burnout syndrome in intensive care unit nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Bras Med Trab.2021;19(3):363-71. DOI: https://doi.org/10.47626/1679-4435-2021-662

18. González-Gil MT, González-Blázquez C, Parro-Moreno AI, Pedraz-Marcos A, Palmar-Santos A, Otero-García L et al. Nurses’ perceptions and demands regarding COVID-19 care delivery in critical care units and hospital emergency services. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;62:102966. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102966

19. Oliveira AC, Lucas TC, Iquiapaza RA. O que a pandemia da Covid-19 tem nos ensinado sobre adoção de medidas de precaução? Texto Contexto Enferm. 2020;29:e20200106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-265x-tce-2020-0106

20. Gallasch CH, Silva RFA, Faria MGA, Lourenção DCA, Pires MP, Almeida MCS et al. Prevalence of COVID-19 testing among health workers providing care for suspected and confirmed cases. Rev Bras Med Trab, 2021;19(2):209-13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.47626/1679-4435-2020-722

21. Bruyneel A, Gallani MC, Tack J, d’Hondt A, Canipel S, Franck S et al. Impact of COVID-19 on nursing time in intensive care units in Belgium. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;62:102967. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102967

22. International Council of Nurses. COVID-19 pandemic one year on: ICN warns of exodus of experienced nurses compounding current shortages. ICN News. [Internet] 2021. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/news/covid-19-pandemic-one-year-icn-warns-exodus-experienced-nurses-compounding-current-shortages

23. Allande-Cussó R, García-Iglesias J.J, Ruiz-Frutos C, Domínguez-Salas S, Rodríguez-Domínguez C, Gómez-Salgado J. Work Engagement in Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Healthcare 2021;9:253. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030253

24. Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, Guo J, Fei D, Wang L et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e15-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X

25. Turale S, Meechamman C, Kunaviktikul W. Challenging times: ethics, nursing and the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Nurs ver. 2020;67(2):164-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12598

26. Liu C, Wang H, Zhou L, Xie H, Yang H, Yu Y et al. Sources and symptoms of stress among nurses in the first Chinese anti-Ebola medical team during the Sierra Leone aid mission: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Sci, 2019;6(2):187-91. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.03.007

27. Shen Y, Zhan Y, Zheng H, Liu H, Wan Y, Zhou W. Anxiety and its association with perceived stress and insomnia among nurses fighting against COVID-19 in Wuhan: A cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(17-18):2654-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15678

28. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang YT, Liu Z, Hu S et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2020;7(4):e17-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8

29. Green C. Spiritual health first aid for self-care. J Christ Nurs. 2021;38(3):E28-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000851

30. Weathers E. What is spirituality? In: Timmins F, Caldeira S. Spirituality in healthcare: Perspectives for innovative practice. Springer Nature. 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04420-6_1

31. Chow SK, Francis B, Ng YH, Naim N, Beh HC, Ariffin MAA, Yusuf MHM, Lee JW, Sulaiman AH. Religious coping, depression and anxiety among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Malaysian perspective. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(1):79. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9010079

32. Theodosio BAL, Ribeiro LF, Andrade MIS, Mpomo JSVMM. Barriers and facilitating factors of multiprofissional health work in the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazilian Journal of Development. 2021;7(4):33998-4016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv7n4-044