|

ARTICLE

Isabelle Pereira da Silva *

Iraktânia Vitorino Diniz **

Julliana Fernandes de Sena ***

Silvia Kalyma Paiva Lucena****

Lorena Brito do O’ *****

Rodrigo Assis Neves Dantas ******

Isabelle Katherinne Fernandes Costa *******

* ![]() 0000-0002-9865-2618 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

0000-0002-9865-2618 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

![]() isabelle.silva.015@ufrn.edu.br

isabelle.silva.015@ufrn.edu.br

** ![]() 0000-0002-0309-6007 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil.

0000-0002-0309-6007 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil.

![]() contato@iraktania.page

contato@iraktania.page

*** ![]() 0000-0002-8968-1521 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

0000-0002-8968-1521 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

![]() julliana.sena.012@ufrn.br

julliana.sena.012@ufrn.br

**** ![]() 0000-0002-1191-927X Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

0000-0002-1191-927X Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

![]() silvia.lucena@ufrn.br

silvia.lucena@ufrn.br

***** ![]() 0000-0002-8419-3457 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

0000-0002-8419-3457 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

![]() lorena.o.702@ufrn.edu.br

lorena.o.702@ufrn.edu.br

****** ![]() 0000-0002-9309-2092 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

0000-0002-9309-2092 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

![]() rodrigo.neves@ufrn.br

rodrigo.neves@ufrn.br

******* ![]() 0000-0002-1476-8702 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

0000-0002-1476-8702 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

![]() isabelle.fernandes@ufrn.br

isabelle.fernandes@ufrn.br

1 This article derives from the master’s thesis “Construction of mobile application prototype to assist in the self-care of people with an intestinal ostomy” of the Graduate Program in Nursing of Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. Available at: https://repositorio.ufrn.br/jspui/handle/123456789/32394. This research was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, public notice CNPq/ MS/SCTIE/Decit 27/2019.

2 El artículo se deriva de la tesis de maestría “Construción de protótipo de aplicación móbil para auxiliar en el autocuidado a personas con ostomías intestinales” en el marco del Programa de Postgrado en Enfermería de la Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Disponible en: https://repositorio.ufrn.br/jspui/handle/123456789/32394. La investigación fue auspiciada por el Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, edital CNPq/MS/SCTIE/Decit 27/2019.

3 Este artigo é derivado da dissertação de mestrado “Construção de protótipo de aplicativo móvel para auxiliar no autocuidado de pessoas com estomias intestinais” do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Enfermagem da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufrn.br/jspui/handle/123456789/32394. La investigación fue auspiciada por el Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, edital CNPq/MS/SCTIE/Decit 27/2019.

Theme: Promotion of health, well-being, and quality of life

Contribution to the discipline: Self-care is an indispensable factor to all human beings and an object of health care. People with ostomies present new demands of self-care that require support to achieve the necessary skills and knowledge. In this sense, this study contributes to expanding the knowledge about the necessary requisites for the person with an ostomy, found in literature, which support the planning and assistance of health professionals, especially nursing, to this population in the process of health education. Moreover, the review can provide the basis for new intervention studies in the area, improving the assistance to this population.

Received: 17/10/2022

Sent to peers: 20/01/2023

Approved by peers: 16/03/2023

Accepted: 23/03/2023

Para citar este artículo / To reference this article / Para citar este artigo Silva IP, Diniz IV, Sena JF, Lucena SKP, Do O’ LB, Dantas RAN et al. Self-care requisites for people with intestinal ostomies: A scoping review. Aquichán. 2023;23(2):e2325. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2023.23.2.5

ABSTRACT

Self-care is one of the

main factors altered in the life of a person with an ostomy.

Self-care requisites with nursing support are necessary.

Objectives: To map the self-care requisites for people with

intestinal ostomies in their adaptive process, guided

by Orem’s theory.

Materials and

methodology: A scoping

review was conducted between May and June 2022, in which studies published from

2000 to 2022 were selected, based on Orem’s self-care deficit nursing theory.

The sources of evidence used were Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval

System Online, Cinahl, Scopus, Latin American and

Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Nursing database, Índice Bibliográfico Español en Ciencias de la Salud, Web of

Science, Scientific Electronic Library Online, Brazilian Digital Library of

Theses and Dissertations, Open Access Scientific Repositories of Portugal,

Theses Canada, DART-Europe E-Theses Portal, and National ETD Portal. Studies

presenting at least one requisite of self-care for people with intestinal ostomies, whether or not they addressed Orem’s theory, and

that were published in full were included. We followed the recommendations of

the Joanna Briggs Institute and the PRISMA International Guide, registered in

the Open Science Framework (10.17605/OSF.IO/XRH5K). The following descriptors

and search strategies were used: (ostomy OR colostomy

OR ileostomy OR stoma) AND (self-care OR self-management) AND (adaptation OR

adjustment).

Results: The final sample was composed of 87 studies. In

universal requisites, studies in the category “nutritional aspects”

predominated, of which the most frequent was “eat regularly and follow a

balanced diet” (23; 26.4%); in developmental requisites, the prevalent category

was “stoma and peristomal skin care” and requisite

“assess peristomal skin integrity” (27; 31.0%); in

the health deviation requisites, the predominant category was “choice of

collection equipment and adjuvant products” and the requisite “use hydrocolloid

powder to absorb moisture in cases of dermatitis” (13; 14.9%).

Conclusions: The study contributes to guiding the assistance

to the person with an ostomy, improving the self-care

learning process. However, new intervention studies are still needed.

Keywords (Source: DeCS) Ostomy; self-care; nursing; health education; nursing models

RESUMEN

El autocuidado es uno de los

principales factores en la vida de la persona con ostomía.

Requisitos de autocuidado con el soporte de la enfermería son necesarios.

Objetivos: mapear los requisitos de autocuidado a personas

con ostomía intestinal en su proceso adaptativo,

norteado por la teoría de Orem.

Materiales y método: revisión de alcance llevada a cabo

entre mayo y junio de 2022, en la que se seleccionaron estudios publicados de

2000 a 2022, desde el marco de la teoría de enfermería del déficit del

autocuidado de Orem. Se emplearon como fuentes de

evidencia Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online, Cinahl, Scopus, Literatura Latinoamericana y del Caribe en Ciencias de la Salud, Base de datos en Enfermería, Índice Bibliográfico Español en Ciencias de la Salud, Web of Science, Scientific Electronic Library Online, Biblioteca Digital Brasileira de Teses e Dissertações, Repositório Científico de Acesso Aberto de Portugal, Theses Canada, DART-Europe E-Theses Portal y National ETD Portal. Se incluyeron estudios que presentaran al menos un requisito de autocuidado a personas con ostomías intestinales, que abordaran o no la teoría de Orem y publicados en la íntegra. Se siguieron las recomendaciones de Joanna Briggs Institute y Prisma International Guide, con registro en la Open Science Framework (10.17605/OSF.IO/ XRH5K). Se emplearon los siguientes descriptores y estrategias de búsqueda: (ostomy OR colostomy OR ileostomy OR stoma) AND (self care OR self-management) AND (adaptation OR adjustment).

Resultados: la muestra final fue de 87 estudios. En los

requisitos universales, predominaron estudios en la categoría “aspectos

nutricionales”, de los cuales el más frecuente fue “comer regularmente y seguir

una dieta balanceada” (23; 26,4 %); en los requisitos de desarrollo, la

categoría prevalente fue “cuidados con la ostomía y

la piel periestomal” y el requisito, “evaluar la

integridad de la piel periestomal” (27; 31,0 %); en

los requisitos de desviación de la salud, la categoría predominante fue “selección

del equipo recolector y los productos adyuvantes”, y el requisito, “usar polvo hidrocoloide para absorber la humidad en casos de

dermatitis” (13; 14,9 %).

Conclusiones: el estudio aporta a la orientación de la atención

a la persona con ostomía, lo que puede mejorar el

proceso de aprendizaje del autocuidado. Sin embargo, nuevos estudios de

intervención aún son necesarios.

Palabras clave (Fuente: DeCS) Ostomía; autocuidado; enfermería; educación en salud; modelos de enfermería

RESUMO

O autocuidado é um dos principais fatores alterados na vida da pessoa com estomia. Requisitos de autocuidado com o apoio da enfermagem são necessários.

Objetivos: mapear os requisitos de autocuidado para pessoas com estomia intestinal em seu processo adaptativo, norteado pela teoria de Orem.

Materiais e método: revisão de escopo realizada entre maio e junho de 2022, na qual foram selecionados estudos publicados de 2000 a 2022, com base no referencial da teoria de enfermagem do déficit do autocuidado de Orem. Utilizaram-se como fontes de evidência Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online, Cinahl, Scopus, Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde, Base de dados em Enfermagem, Índice Bibliográfico Español en Ciencias de la Salud, Web of Science, Scientific Electronic Library Online, Biblioteca Digital Brasileira de Teses e Dissertações, Repositório Científico de Acesso Aberto de Portugal, Theses Canada, DART-Europe E-Theses Portal e National ETD Portal. Incluíram-se estudos que apresentassem pelo menos um requisito de autocuidado para pessoas com estomias intestinais, que abordassem ou não a teoria de Orem e publicados na íntegra. Seguiram-se as recomendações da Joanna Briggs Institute e do Prisma International Guide, com registro na Open Science Framework (10.17605/OSF.IO/XRH5K). Usaram-se os seguintes descritores e estratégias de busca: (ostomy OR colostomy OR ileostomy OR stoma) AND (self care OR self-management) AND (adaptation OR adjustment).

Resultados: a amostra final foi composta de 87 estudos. Nos requisitos universais, predominaram estudos na categoria “aspectos nutricionais”,

dos quais o mais frequente foi “comer regularmente

e seguir uma dieta equilibrada” (23; 26,4 %); nos

requisitos de desenvolvimento, a categoria prevalente foi “cuidados com a estomia e a pele periestomal”

e o requisito, “avaliar a integridade da pele periestomal” (27; 31,0 %); nos requisitos de desvio de saúde, a categoria predominante foi “escolha do equipamento coletor e dos produtos adjuvantes”, e o requisito, “usar pó hidrocoloide para absorver a umidade em casos de dermatite” (13; 14,9 %).

Conclusões: o estudo contribui para nortear a assistência à pessoa com estomia, melhorando o processo de aprendizado do autocuidado. Contudo, novos estudos de intervenção ainda são necessários.

Palavras-chave (Fonte DeCS) Estomia; autocuidado; enfermagem; educação em saúde; modelos de enfermagem

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal ostomies consist of surgical openings to exteriorize a segment of the intestine to supply the needs of fecal elimination (1). The process of living with an ostomy has repercussions on biopsychosocial aspects and promotes changes and adaptations in people’s daily habits, self-care, and self-image (2).

Self-care is one of the main factors altered in the life of a person with an ostomy, due to the new demands of body care that permeate aspects such as body hygiene, stoma and peristomal skin, nutrition, sexuality, social relations, and psychological factors. Insufficient self-care can lead to complications associated with the stoma and hinder the adaptive process (3).

Dorothea Orem defines self-care as actions that people perform to maintain the functioning and well-being of the body, preserving organic development, health, and life. When there is an imbalance between the demands and the ability to perform these actions, there is a self-care deficit, a situation in which the nurse plays an important role in supporting the patient who has difficulties in self-care (4).

People with ostomies experience deficits, especially during the initial period after surgery, related to the new skills required in the care of the ostomy and the collection equipment, as well as the psychological and social repercussions (5). These aspects derive from problems of acceptance and aversion to touch or care for the stoma, and from difficulties with the required skills and in the process of learning about self-care (3, 6).

Such factors need to be developed and directed by the nurse in the process of health education, in which the person with an ostomy, along with caregivers and family members, has a central and active role. For this, Orem establishes essential actions for the provision of self-care, called “requisites”, which can be universal when they concern the maintenance of life, developmental when related to body changes or new events, and of health deviation when associated with pathologies or injuries (4).

It is fundamental that people with ostomies develop these requisites in their learning process of self-care with the support of nursing, especially because the nurse has an important role in the performance of healthcare services for people with ostomies within the Unified Health System (SUS, by its acronym in Portuguese), participating in the comprehensive assistance to the population, as well as in the duties of organizing services (7).

In this sense, this study is justified by the need to expand the knowledge of nurses about the requisites of self-care, aiming to improve the assistance provided, in addition to giving information that can support the development of technologies and educational methods for the self-care of this population. Therefore, the objective of the study is to map the self-care requisites for people with intestinal ostomies in their adaptive process, guided by Orem’s theory.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

The study consists of a scoping review conducted from May to June 2022, based on the theoretical framework of Orem’s selfcare deficit nursing theory (4), in which studies published from 2000 to 2022 were selected. We followed the protocol of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewers’ Manual: delimitation of the research question, surveys of studies in the literature, selection based on eligibility criteria, data analysis, synthesis, and presentation (8). For the structured presentation of results, the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR [9]) were followed.

A search for protocols similar to this review was performed in April 2022 in the JBI Clinical Online Network of Evidence for Care and Therapeutics (COnNECT+), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), The Cochrane Library, and International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPE-RO) data sources. It was found that there are no protocols similar to the purpose of this study.

After that, a search protocol was created with the following items: objective, guiding question (mnemonic “Population, Concept, Context - PCC”), inclusion and exclusion criteria, search strategy, data to be extracted from the studies, and form of presentation of results. The study protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform under the DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/XRH5K.

The guiding question was elaborated from the mnemonic “PCC”, in which “P” indicates people with intestinal ostomies; “C”, selfcare requisites; “C”, adaptive process. In this way, the aim is to question what self-care requisites are necessary for people with ostomies in their adaptive process.

The descriptors were selected in the indexed vocabulary of the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Descriptors in Health Sciences (DeCS); in addition, the keywords were searched in the studies available in the National Library of Medicine (PubMed) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (Cinahl), according to the recommendations of the JBI. Based on this, the following search strategy was elaborated: (ostomy OR colostomy OR ileostomy OR stoma) AND (self-care OR self-management) AND (adaptation OR adjustment).

The following data sources were used: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (Medline), Cinahl, Scopus, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (Lilacs, by its acronym in Portuguese), Nursing Database (BDEnf, by its acronym in Portuguese), Índice Bibliográfico Español en Ciencias de la Salud (IBECS), Web of Science, and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO). Regarding the gray literature sources, studies were sought in the Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (BDTD, by its acronym in Portuguese), the Open Access Scientific Repository of Portugal (RCAAP, by its acronym in Portuguese), Theses Canada, the DART-Europe E-Theses Portal, and the National ETD Portal.

Due to the specifications of the data sources, the search strategy was adapted to each of them, but we tried to keep it as similar as possible to the original strategy. Table 1 presents the strategies used for each source.

Table 1 Search Strategies Conducted in Each Data Source. Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, 2022

Search Strategies |

Source |

TI ostomy OR TI colostomy OR TI ileostomy OR TI stoma AND TI self care OR TI selfmanagement AND TI adaptation OR TI adjustment |

Medline |

TI ostomy OR TI colostomy OR TI ileostomy OR TI stoma AND TI self care OR TI selfmanagement AND TI adaptation OR TI adjustment |

Cinahl |

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (ostomy) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (colostomy) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (ileostomy) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (stoma) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (self AND care) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (self AND management) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (adaptation) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (adjustment)) |

Scopus |

(tw:(ostomy)) OR (tw:(colostomy)) OR (tw:(ileostomy)) OR (tw:(stoma)) AND (tw:(self-care)) OR (tw:(self-management)) AND (tw:(adaptation)) OR (tw:(adjustment)) |

Lilacs |

(tw:(ostomy)) OR (tw:(colostomy)) OR (tw:(ileostomy)) OR (tw:(stoma)) AND (tw:(self-care)) OR (tw:(self-management)) AND (tw:(adaptation)) OR (tw:(adjustment)) |

BDEnf |

(tw:(ostomy)) OR (tw:(colostomy)) OR (tw:(ileostomy)) OR (tw:(stoma)) AND (tw:(self-care)) OR (tw:(self-management)) AND (tw:(adaptation)) OR (tw:(adjustment)) |

IBECS |

(tw:(ostomy)) OR (tw:(colostomy)) OR (tw:(ileostomy)) OR (tw:(stoma)) AND (tw:(self-care)) OR (tw:(self-management)) AND (tw:(adaptation)) OR (tw:(adjustment)) |

SciELO |

(all fields: ostomy AND all fields: self-care) |

BDTD |

Ostomy OR (colostomy OR ileostomy OR stoma) AND self-care OR (self-management) AND adaptation OR (adjustment) |

RCAAP |

Ostomy OR colostomy OR ileostomy OR stoma AND self-care OR self-management AND adaptation OR adjustment |

Theses Canada |

Ostomy OR colostomy OR ileostomy OR stoma AND self-care OR self-management AND adaptation OR adjustment |

DART-Europe E-Theses Portal |

Ostomy OR (colostomy OR ileostomy OR stoma) AND self-care OR (self-management) AND adaptation OR (adjustment) |

National ETD Portal |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The eligibility criteria included studies that presented at least one requisite of self-care (actions aimed at the provision of selfcare [4]) for people with intestinal ostomies, whether or not they addressed Orem’s theory, and that were published in full online in the Journals Portal of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes, by its acronym in Portuguese). Access to the portal was through the Federated Academic Community (CAFe, by its acronym in Portuguese), a resource funded by the university where the study was conducted. Duplicates, editorials, experience reports, opinion articles, and theoretical essays were excluded.

The studies were initially selected based on the titles and abstracts, and after the initial sorting, they were read in full for the sample selection. The search was conducted by two researchers independently, and at the end, the selected texts were compared and read in their entirety. In case of disagreement, a third researcher delimited the study to be included. No software was used in the process of selection and analysis of the studies.

The self-care requisites were grouped as proposed by Orem (5): universal when they addressed basic activities of daily living for the functioning of the body, developmental when related to specialized actions of the universal requisites for changes in body development or new conditions or events, and health deviation for situations of diseases or injuries that require diagnostic, therapeutic or rehabilitative care actions. Moreover, the requisites were subdivided into thematic categories based on the Brazilian Consensus on Stomal Therapy (10).

The selected studies were identified by the letter “E”, from E1E83 (6, 11 - 96). The data extracted from the studies of the final sample (identification data, type of study, and recommendations for self-care) were tabulated in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, analyzed according to descriptive statistics, and presented in table format.

RESULTS

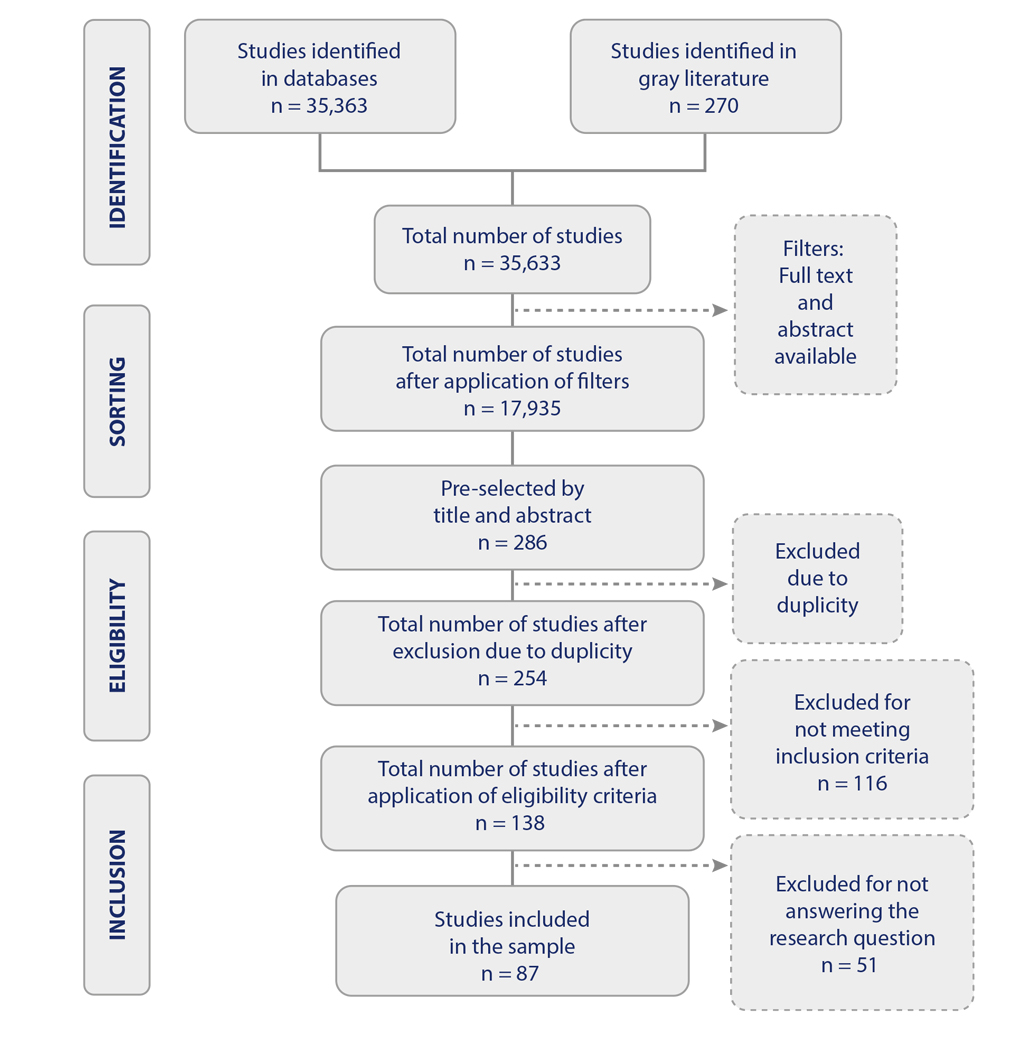

A total of 35,363 studies were identified in the databases and gray literature, of which 87 were selected to compose the sample, as detailed in the diagram of Figure 1. Of this total, 78 are articles, with eight dissertations and one thesis.

Figure 1. Diagram of Study Selection from Data Sources. Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, 2022

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Regarding the characterization of the studies in the sample, it was found that most were from the Cinahl database (52; 59.8%) and the British Journal of Nursing (18; 20.7%), published in the United Kingdom (40; 46.0%) and carried out in the United Kingdom (44; 50.6%). The publications occurred between 2000 and 2022, mostly in the years 2019 (9; 10.3%), 2013 (8; 9.2%), and 2014 (7; 8.0%), and were found to be predominantly literature reviews (50; 57.5%). Regarding self-care requisites, 78 requisites were identified, of which 19 were classified as universal, 41 as developmental, and 18 as health deviation.

Concerning the universal requisites, described in Table 2, most studies were identified in the category “nutritional aspects”, of which the most frequent was “eating regularly and following a balanced diet”. In addition, within this category, the least frequent were “observe the effects of dietary changes on stool” (5; 5.7% [29, 36, 73, 78, 92]), “avoid consuming large amounts of fluid during or immediately before or after meals” (4; 4.6% [14, 22, 32, 34], “avoid talking while eating” (3; 3.4% [56, 75, 78]), “avoid foods that may cause obstruction” (3; 3.4% [16, 21, 73]), “avoid foods that cause diarrhea” (3; 3.4% [14, 15, 52]), and “control foods that cause odor” (2; 2.3% [18, 78]).

Table 2 Absolute and Relative Frequency of the Universal Requisites Identified in the Studies. Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, 2022

Universal requisites |

Studies |

n (%) |

Nutritional aspects |

||

Eat regularly and follow a balanced diet |

E2, E6, E12, E13, E15, E16, E17, E18, E19, E20, E23, E27, E29, E33, E40, E46, E48, E49, E67, E69, E71, E75, E84. |

23 (26.4) |

Maintain a good fluid intake |

E2, E4, E8, E9, E17, E19, E20, E24, E27, E33, E40, E46, E48, E49, E51, E56, E67, E69. |

18 (20.7) |

Avoid gas-producing foods |

E2, E12, E13, E15, E17, E51, E56, E63, E67, E69, E71, E80, E81, E82. |

14 (16.1) |

Masticate food thoroughly |

E2, E12, E17, E19, E27, E33, E37, E40, E46, E48, E56, E67, E69, E71. |

14 (16.1) |

Taste foods gradually |

E12, E17, E20, E23, E24, E27, E33, E40, E56, E69, E71. |

11 (12.6) |

Intestinal control |

||

Watch for signs of change in the stool |

E5, E7, E37, E45, E53, E63, E86. |

7 (8.0) |

Physical activities |

||

Perform moderate physical exercises to prevent constipation |

E19, E20, E39, E51. |

4 (4.6) |

Take walks to help stimulate bowel function and muscle tone |

E39, E40, E62. |

3 (3.4) |

Professional clinical advice should be sought before beginning any kind of exercise |

E39, E40. |

2 (2.3) |

Sexuality |

||

Express concerns and doubts about sexual aspects and body image |

E66, E73, E75, E84. |

4 (4.6) |

Explore other comfortable positions for sexual activities |

E66, E73, E83. |

3 (3.4) |

Accept to adapt to changes and self-image after the ostomy |

E85, E87. |

2 (2.3) |

Discuss aspects that can improve self-image with health-care professionals |

E36. |

1 (1.1) |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

As for the developmental requisites, described in Table 3, the predominance of the category “stoma and peristomal skin care” and the requisite “assess peristomal skin integrity” were observed. In this category, the least frequent requisites were “keep the peristomal skin clean and dry” (4; 4.6% [43, 46, 67, 74]), “cut the peristomal skin hairs” (3; 3.4% [45, 79, 83]), “measure the length and width of irregular stomas” (2; 2.3% [45, 63]), and “expose the skin around the stoma to the sun” and “protect the stoma with moist gauze” (1; 1.1% [83]).

Table 3 Absolute and Relative Frequency of the Developmental Requisites Identified in the Studies. Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, 2022

Developmental Requisites |

Studies |

n (%) |

Stoma and Peristomal Skin Care |

||

Assess peristomal skin integrity |

E20, E26, E23, E25, E29, E32, E33, E35, E37, E38, E40, E43, E46, E47, E50, E52, E53, E54, E55, E56, E58, E67, E68, E69, E72, E76, E86. |

27 (31.0) |

Clean the peristomal skin with tap water and dry thoroughly |

E1, E9, E15, E17, E19, E21, E22, E25, E26, E29, E38, E40, E41, E56, E57, E58, E67, E69, E72, E76, E81, E82. |

22 (25.3) |

Check the normal appearance of the stoma |

E3, E4, E7, E9, E15, E17, E20, E24, E27, E29, E40, E41, E43, E46, E50, E52, E67, E72, E76, E77. |

20 (23.0) |

Assess the viability of the ostomy and its characteristics |

E7, E8, E25, E29, E35, E38, E50, E52, E55, E68, E72, E76. |

12 (13.8) |

Avoid the use of moisturizers on the peristomal skin |

E29, E41, E56, E58, E68, E69, E76. |

7 (8.0) |

Choice of Collection Equipment and Supplies |

||

The opening of the base plate should be cut in the diameter of the stoma |

E1, E3, E7, E8, E13, E14, E17, E20, E24, E29, E38, E40, E41, E50, E58, E61, E68, E72, E76, E77. |

20 (23.0) |

Use products that act as a barrier to protect the peristomal skin |

E3, E8, E17, E19, E21, E24, E26, E32, E38, E44, E46, E47, E50, E57, E58, E65, E68, E69, E72. |

19 (21.8) |

Remove the collection bag carefully |

E1, E3, E15, E17, E21, E22, E25, E38, E57, E58, E67, E69, E72, E76, E77. |

15 (17.2) |

Measure the stoma to define the size of the collection bag cutout |

E15, E17, E23, E24, E25, E29, E38, E40, E56, E61, E67, E76, E77. |

13 (14.9) |

Empty the bag when it is 1/3 or even 1/2 full |

E1, E3, E7, E9, E17, E29, E33, E40, E56, E69, E72, E76. |

12 (13.8) |

Choice of Collection Equipment and Supplies |

||

Choose the collection equipment according to the needs, individual characteristics, and type of stoma |

E10, E11, E12, E22, E23, E37, E41, E52, E68, E69, E72, E76, E85. |

13 (14.9) |

Use products for stomas to fill skin folds and level the skin |

E3, E8, E19, E32, E38, E40, E41, E44, E50, E60, E72. |

11 (12.6) |

Use bags with activated charcoal filters for the neutralization of odor |

E12, E17, E51, E56, E67, E69, E71, E74, E77, E78. |

10 (12.0) |

Use a transparent collection bag when it is necessary to visualize the stoma |

E4, E7, E12, E41, E72, E77. |

6 (6.9) |

Use deodorant sprays in the bag to control odors |

E27, E44, E51, E56, E69, E71. |

6 (6.9) |

Nutritional Aspects |

||

Decrease fiber intake for people with ileostomies |

E2, E12, E24, E27, E31, E33, E43, E49. |

8 (9.2) |

Maintain adequate fiber food and fluid intake for people with colostomies |

E24, E46, E48, E51, E63, E69. |

6 (6.9) |

Recognize symptoms of dehydration in people with ileostomies |

E2, E30, E59, E67. |

4 (4.6) |

Sexuality |

||

Use alternative strategies such as underwear and belts to encourage intimacy |

E6, E37, E62, E66, E73, E75, E83. |

7 (8.0) |

Empty or replace the collection bag before intercourse |

E6, E64, E66, E73, E75. |

5 (5.7) |

Avoid foods that can cause gas or strong odors before intercourse |

E66, E75. |

2 (2.3) |

Clinical Assistance |

||

Express concerns or anxieties in conversations with health-care professionals |

E36, E37, E40, E64, E70, E73, E75, |

6 (6.9) |

Seek help from professionals to evaluate the possibility of using continence systems |

E6, E64, E75, |

3 (3.4) |

Social Aspects |

||

Participate in groups with other people with ostomies |

E23, E74, E86, E87. |

4 (4.6) |

Physical Activities |

||

Empty the collection bag before physical activities |

E67, E76. |

2 (2.3) |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

In the category “care of the collection equipment and supplies”, it was observed that “assess peristomal skin integrity” was the most common requisite. The least frequent requisites were “carefully remove adhesive parts of the collection equipment” (10; 12.0% [ 25, 28, 40, 41, 43, 46, 50, 71, 75, 77]), “check for signs of leakage in the collection equipment” (9; 10.3% [ 20, 25, 27, 33, 43, 47, 60, 74, 79]), “adjust the opening of the collection equipment in the first weeks after surgery” (7; 8.0% [29, 45, 47, 51, 74, 79, 92]), “carefully place the collection equipment around the stoma” (6; 6.9 % [ 16, 24, 25, 73, 83, 84]), “take extra supplies and collection equipment when away from home” (6; 6.9% [ 6, 15, 75, 83, 86, 87]), “fix the collection equipment correctly from bottom to top on the peristomal skin” (6; 6.9% [11, 27, 33, 41, 83, 84]), “identify and perform the change of the collection equipment when the plate is saturated” (5; [ 18, 44, 67, 75, 83]), “when changing the collection equipment, keep it pressed for a few seconds” (4; 4.6% [ 26, 41, 83, 84]), “apply the barrier cream in circular movements with the fingertip” (3; 3.4% [ 28, 51, 62]), and “monitor the adaptation to the collection equipment” (2; 2.3% [ 93, 95]).

The category “choice of the collection equipment and supplies” had the most common requisite for choosing the collection equipment according to the needs, individual characteristics, and type of stoma. And the requisite “patients along with the nurse select the appropriate collection equipment” was the least frequent (3; 3.4% [ 25, 54, 83]).

Table 4 presents the health deviation requisites, which had “choice of collection equipment and supplies” as the most frequent category, and the requisite “use hydrocolloid powder to absorb moisture in cases of dermatitis”. In this category, the least frequent requisites were “change the collection equipment in case of allergic dermatitis” (8; 9.2% [ 17, 21, 25, 46, 58, 67, 71, 77]), “use barrier products and rings in the presence of granulomas” (6; 6.9% [ 25, 43, 58, 69, 71, 88]), and “use Aloe vera may help in the management of peristomal complications” (1; 1.1% [ 30,]).

Table 4 Absolute and Relative Frequency of Health Deviation Requisites Identified in the Studies. Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, 2022

Health Deviation Requisites |

Studies |

n (%) |

Choice of Collection Equipment and Supplies |

||

Use hydrocolloid powder to absorb moisture in cases of dermatitis |

E8, E13, E19, E24, E26, E32, E41, E50, E57, E60, E65, E68, E69. |

13 (14.9) |

Managing contact dermatitis treatment using ostomy skin barriers |

E7, E20, E26, E37, E38, E40, E42, E50, E54, E61, E65, E69. |

12 (13.8) |

Use a bag with convex barrier rings in cases of retraction |

E7, E8, E16, E23, E34, E37, E53, E63, E65, E69, E72. |

10 (12.0) |

Manage the parastomal hernia with the use of a support belt, one-piece systems, and skin protection products |

E1, E5, E7, E20, E23, E46, E53, E63, E65, E69. |

10 (12.0) |

Identify and manage the underlying cause of stomal complications |

E23, E32, E38, E46, E53, E57, E61, E68, E69, E84, E85. |

11 (12.6) |

Stoma and Peristomal Skin Care |

||

Monitor the extent of necrosis, assessing the stoma and peristomal skin |

E4, E23, E37, E40, E65, E69. |

6 (6.9) |

Observe signs of ischemia when the stoma presents stenosis |

E4, E7, E20, E53, E63. |

5 (5.7) |

Observe signs of stoma obstruction in case of complications |

E5, E86. |

2 (2.3) |

Prevent stomal and peristomal complications |

E85, E86. |

2 (2.3) |

Demonstrate strategies for the resolution of stomal and peristomal complications |

E86. |

1 (1.1) |

Clinical Assistance |

||

Seek nursing professional help in case of stomal and peristomal complications |

E46, E52, E56, E67, E68, E72, E76, E86, E87. |

9 (10.3) |

Seek professional help when effluents are above normal volume |

E30, E56, E67, E86. |

4 (4.6) |

Nutritional Aspects |

||

Use oral rehydration in case of large losses of fecal content |

E59, E67. |

2 (2.3) |

Physical Activities |

||

Discontinue exercise in case of health problems |

E39. |

1 (1.1) |

Sexuality |

||

Seek professional help to evaluate physiological problems related to sexual activities |

E6, E62, E64, E66, E73. |

5 (5.7) |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

DISCUSSION

It was observed that the studies mapped mainly requisites on aspects of care with the stoma and the peristomal skin, nutritional aspects, and the choice of collection equipment and supplies. Moreover, most of the requisites were developmental, related to the changes that people with ostomies face both in body aspects and in activities of daily living. Such findings indicate the need for professionals to emphasize these aspects in the process of health education.

The universal requisites presented the nutritional aspects as the most frequent category, with requisites that addressed proper nutrition, fluid intake, and bowel control, including the observation of changes in the stool. Orem establishes the provision of sufficient food for the needs of body integrity, as well as the care related to elimination needs as essential for self-care. This principle should be considered by nursing, which should support this process so that the individual can manage food choices and control excrement (4).

Given this need, it becomes essential to monitor the changes in eating habits that people with intestinal ostomies experience since nutrition influences bowel function and elimination, which can generate undesirable effects, such as the increase of flatus, associated with the stoma type (97, 98), resulting in poorer quality of life, since the loss of consumption of certain foods may deprive the pleasurable sensations associated with eating ( 99, 100).

In this sense, it is necessary that, in this population’s assistance, the orientations about nutritional aspects are included, as well as the available strategies that can help the person in their autonomy, such as the practice of irrigation, if the individual meets the conditions required to perform it (98). Furthermore, the joint work of nursing with the multi-professional team is highlighted, through the services of attention to the health of the person with an ostomy, which has, in the scope of SUS, multi-professional assistance that includes nutritionists to meet the needs of nutritional and dietary assessment (7).

Regarding the developmental requisites, the predominant category was “stoma and peristomal skin care”, with emphasis and more frequency on the requisite “assessment of peristomal skin integrity”, followed by the categories “care and choice of the collection equipment and supplies”, which presented requisites on the correct use and handling of this equipment and the choice of products for self-care. These results are related to the changes experienced and the new self-care needs, which require specific actions for the proper functioning of the ostomy and the protection against complications, in which the support of the nursing team is of fundamental importance.

For this reason, the assessment of the peristomal skin integrity is one of the essential care after having an ostomy, to prevent complications associated with the use of the collection system and the contact of stool with the skin (25). The latest recommendations encourage nurses to enable the patient to assess their stoma and peristomal skin, so that they can actively participate in the care and identify changes for preventive care, with the support of health professionals (10).

Among the factors that can interfere with the integrity of the peristomal skin, the inadequate handling of collection equipment, effluent leakage, and the self-care deficit related to hygiene are highlighted (3). These difficulties occur mainly during the initial period after surgery, which generates feelings of anxiety and insecurity. Therefore, adequate instruction about this care provides greater safety and satisfaction to this population, especially when performed by nurses with specialized knowledge in stomal therapy (101).

Regarding the requisites related to the collection equipment, we emphasize the importance of the choice f the collection equipment being made in a participative way between nurses and the population with an ostomy. In the context of the SUS, the collection equipment and supplies are made available in the care services for people with ostomies free of charge, and when selected appropriately and periodically reassessed, they provide confidence and satisfaction to the person with an ostomy (102), besides contributing to the resolution of complications (7).

The selection of the collection equipment follows the nurse’s prescription, which must be based on the individuality of each person, considering the aspects of the patient’s preference, type of ostomy, adaptation, peristomal skin, and characteristics of the person’s abdomen (10).

As for the health deviation requisites, the main category referred to the choice of the collection equipment and supplies, in which the main requisite dealt with the use of hydrocolloid powder to absorb moisture in cases of dermatitis. This category, as well as that of stoma and peristomal skin care, indicated mainly the handling of stomal and peristomal complications, present in several studies.

Complications, besides negatively impacting the adaptation of people with ostomies, cause costly expenses for health services. Thus, the population can benefit from more emphasis on preventive education rather than only receiving curative treatment (103).

Several products are available to assist in the prevention and treatment of stomal and peristomal complications, such as barrier films, adhesive removers, pastes, and powders with actives that protect or assist in the healing of lesions. It is necessary to assess not only the lesion but also the person with an ostomy as a whole, given the impact that this complication can cause in their lives, to then designate a specific conduct for each situation (104).

Regarding the categories of physical activities, sexuality, and social aspects present in the requisites, this review highlights the scarcity of research on these topics. This can be explained because, in self-care, the emphasis is notoriously on practical skills related to ostomy care, along with the peristomal skin and the collection equipment.

However, the repercussions of an ostomy transcend the physiological changes and alter how the person sees him or herself and how he or she relates to other people as a result (105). According to Orem, health deviation requisites also encompass the need to accept self-image modifications arising from treatments, health conditions, or illness (4). Thus, a multidimensional nursing approach that focuses, in addition to physical changes, on emotional, sexual, and social aspects is imperative to assist in the self-care of this population.

It is also noteworthy that self-care involves not only the practical care with the ostomy and the collection equipment, but also the psychological, physical, and environmental needs (4). Thus, sensitivity and knowledge of nursing are crucial to identifying the main needs of this population, in an individualized and holistic way, to provide the demands of self-care.

Some strategies and educational technologies are being produced and have shown positive effects on health education, which can support nursing care to the person with an ostomy for the provision of self-care (106). Considering the requisites identified in this study, it is expected to assist in the planning of interventions for the self-care of this population, as well as in new studies for the advancement of knowledge in the area.

As a limitation, this review presents the mapping of the requisites identified in different types of studies without assessing the degree of evidence and indication for clinical practice. More studies are needed to understand these requisites based on the experiences of people with ostomies and evidence-based research, using Orem’s theory to support nursing care for this population.

CONCLUSIONS

This study presented the main self-care requisites mapped in the literature and guided by Orem’s theory. The universal requisites mainly addressed nutritional aspects; for the developmental requisites, the stoma and peristomal skin care predominated; as for the main health deviation requisites, they dealt with the choice of the collection equipment and supplies in case of complications. Few studies addressed the categories “physical activities”, “sexuality”, and “social aspects.”

Therefore, the requisites identified in this study can guide nursing care to the person with an ostomy, improving the assistance provided and the process of learning self-care. Furthermore, the study contributes to the advancement of nursing as a science by presenting the mapping of evidence based on a nursing theory. New intervention studies and the development of technologies based on the results of this review are suggested.

Conflict of interest: Non to declare

REFERENCES

1. United Ostomy Associations of America. New ostomy patient guide [Internet]. United States of America: The Phoenix; 2020. Available from: https://www.ostomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/UOAA-New-Ostomy-Patient-Guide-2020-10.pdf

2. Tomasi AVR, Santos SMA, Honório GJS, Girondi JBR. Living with an intestinal ostomy and urinary incontinence. Texto Contexto Enferm [Internet]. 2022;31:e20210115. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-265x-tce-2021-0398en

3. Freire DDA, Angelim RCDM, Souza NRDE, Brandão BMGDM, Torres KMS, Serrano SQ. Self-image and self-care in the experience of ostomy patients: The nursing look. REME Rev Min Enferm [Internet]. 2017;21:e-1019. Disponível em: http://www.revenf.bvs.br/pdf/reme/v21/en_1415-2762-reme-20170029.pdf

4. Orem DE. A concept of self-care for the rehabilitation client. Rehabil Nurs [Internet]. 1985;10(3):33-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.1985.tb00428.x

5. Ribeiro WA, Andrade M, de Souza Couto C, Mendes da Silva Souza D, Costa de Morais M, Mendes Santos JA. Perspectiva do paciente estomizado intestinal frente a implementação do autocuidado. Rev Pró-UniverSUS [Internet]. 2020;11(1):6-13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21727/rpu.v10i1.1683

6. Sun V, Bojorquez O, Grant M, Wendel CS, Weinstein R, Krouse RS. Cancer survivors’ challenges with ostomy appliances and self-management: A qualitative analysis. Support Care Cancer [Internet]. 2020;28(4):1551-554. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05156-7

7. Freitas J, Borges E, Bodevan E. Characterization of the clientele and evaluation of health care service of the person with elimination stoma. Rev Estima [Internet]. 2018;16:e0918. DOI: https://doi.org/10.30886/estima.v16.402

8. Aromataris E, Munn Z (editores). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

9. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Check-list and explanation. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2018;169(7):46773. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

10. Paula MAB, Moraes JT. Um consenso brasileiro para os cuidados às pessoas adultas com estomias de eliminação. ESTIMA. Braz J Enterostomal Therapy. 2019;19:e0221. DOI: https://doi.org/10.30886/estima.v19.1012_PT

11. Burch J. Caring for peristomal skin: What every nurse should know. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2010;19(3):166-72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2010.19.3.46538

12. Readding L. Practical guidance for nurses caring for stoma patients with long-term conditions. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2016;21(2):90-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2016.21.2.90

13. Bowles T, Readding L. Caring for people with arthritis and a stoma. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2013;22(sup11):S14-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2013.22.Sup11.S14

14. Bradshaw E, Collins B. Managing a colostomy or ileostomy in community nursing practice. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2008;13(11):514-18. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2008.13.11.31523

15. Tao H, Songwathana P, Isaramalai S, Wang Q. Taking good care of myself: A qualitative study on self-care behavior among Chinese persons with a permanent colostomy. Nurs Health Sci [Internet]. 2014;16(4):483-89. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12166

16. O’Connor G. Teaching stoma-management skills: The importance of self-care. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2005;14(6):320-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2005.14.6.17800

17. Martin ST, Vogel JD. Intestinal Stomas. Adv Surg [Internet]. 2012;46(1):19-49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yasu.2012.04.005

18. Thompson J. A practical ostomy guide. Part one. RN [Internet]. 2000;63(11):61-6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11147012

19. Floruta C. Dietary choices of people with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs [Internet]. 2001;28(1):28-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1067/mjw.2001.112079

20. Watson AJ, Nicol L, Donaldson S, Fraser C, Silversides A. Complications of stomas: Their aetiology and management. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2013;18(3):111-16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2013.18.3.111

21. Burch J. The pre-and postoperative nursing care for patients with a stoma. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2005;14(6):310-18. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2005.14.6.17799

22. Fulham J. Providing dietary advice for the individual with a stoma. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2008;17(1):S22-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.Sup1.28146

23. Burch J. When to use a barrier cream in patients with a stoma. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2021 Sept 15];22(5):S12. DOI: DOI: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23568318/

24. Howson R. Stoma education for the older person is about keeping it as simple as 1, 2, 3. J Stomal Ther Aust [Internet]. 2019;39(3):20-2. Available from: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.676997449540767

25. Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. WOCN society clinical guideline: Management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy-An executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs [Internet]. 2018;45(1):50-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000396

26. Burch J. Stoma management: Enhancing patient knowledge. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2011;16(4):162-66. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2011.16.4.162

27. Villa G, Vellone E, Sciara S, Stievano A, Proietti MG, Manara DF et al. Two new tools for self‐care in ostomy patients and their informal caregivers: Psychosocial, clinical, and operative aspects. Int J Urol Nurs [Internet]. 2019;13(1):23-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijun.12177

28. Kelly-O’Flynn S, Mohamud L, Copson D. Medical adhesive-related skin injury. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2020;29(6):S20-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2020.29.6.S20

29. Barbara BM. Stoma management and palliative care. J Community Nurs [Internet];25(4):4-10. Available from: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A260801678/AONE?u=anon~bd0db09c&sid=googleScholar&xid=f665b045

30. Rippon M, Perrin A, Darwood R, Ousey K. The potential benefits of using aloe vera in stoma patient skin care. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2017;26(5):S12-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.5.S12

31. Blevins S. Colostomy Care. Medsurg Nurs [Internet]. 2019;28(2):125-26. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/colostomy-care/docview/2213046219/se-2

32. Goodey A, Colman S. Safe management of ileostomates with high-output stomas. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2016;25(22):S4-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2016.25.22.S4

33. Burch J. Peristomal skin care and the use of accessories to promote skin health. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2011;20(supl. 3):S4-10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2011.20.Sup3.S4

34. Stankiewicz M, Gordon J, Rivera J, Khoo A, Nessen A, Goodwin M. Clinical management of ileostomy high-output stomas to prevent electrolyte disturbance, dehydration and acute kidney injury: A quality improvement activity. J Stomal Ther Aust [Internet]. 2019;39(1):8-10. Available from: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/INFORMIT.231837133211111

35. Metcalf C. Managing moisture-associated skin damage in stoma care. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2018;27(22):S6-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2018.27.22.S6

36. Burch J. Stoma formation. J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2011;25(3):36-8. Available from: https://www.jcn.co.uk/journals/issue/05-2011/article/stoma-formation

37. Slater R. Choosing one-and two-piece appliances. Nurs Resid Care [Internet]. 2012;14(8):410-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/nrec.2012.14.8.410

38. Whiteley I. Educating a blind person with an ileostomy: Enabling self-care and independence. J Stomal Ther Aust. 2013;33(3):6-8. Available from: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.603543128039232

39. Houston N. Reflections on body image and abdominal stomas. J Stomal Ther Aust [Internet]. 2017;37(3):8-12. Available from: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.136125246047872%0A

40. Dorman C. Ostomy basics. RN [Internet]. 2009;72(7):22-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19645224

41. Burch J. Peristomal skin care considerations for community nurses. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2019;24(9):414-18. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2019.24.9.414

42. Hey S. Fitness and wellbeing after stoma surgery. J Stomal Ther Aust [Internet]. 2018;38(1):8-10. Disponível em: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.582049514199114

43. Schreiber ML. Ostomies: Nursing care and management. Medsurg Nurs [Internet]. 2016;25(2):127-30. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27323475

44. Cronin E. Colostomies and the use of colostomy appliances. Br J Nurs [Internet];17(supl. 7):S12-9.DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.Sup7.31117

45. Pontieri-Lewis V. Basics of ostomy care. Medsurg Nurs [Internet]. 2006;15(4):199-202. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16999180

46. Thompson H, North J, Davenport R, Williams J. Matching the skin barrier to the skin type. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2011;20(supl 9):S27-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2011.20.Sup9.S27

47. Burch J. Stoma care: an update on current guidelines for community nurses. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2017;22(4):1626. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.4.162

48. Fake J, Skipper G. Key messages in prescribing for stoma care. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2014;23(supl 17):S17-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2014.23.Sup17.S17

49. Dukes S. Considerations when caring for a person with a prolapsed stoma. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2010;19(Sup7):S21-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2010.19.Sup7.78571

50. Burch J. Caring for the older ostomate: An update. Nurs Resid Care [Internet]. 2006;8(3):117-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/ nrec.2006.8.3.20558

51. Rudoni C. Peristomal skin irritation and the use of a silicone-based barrier film. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2011;20(supl 9):S128. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2011.20.Sup9.S12

52. Burc J. Dietary considerations for the older ostomate. Nurs Resid Care [Internet];8(8):354-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/nrec.2006.8.8.21553

53. Burch J. Nutrition and the ostomate: Input, output and absorption. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2006;11(8):349-51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2006.11.8.21669

54. Burch J. Maintaining peristomal skin integrity. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2018;23(1):30-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2018.23.1.30

55. Shabbir J, Britton DC. Stoma complications: A literature overview. Colorectal Dis [Internet]. 2010;12(10):958-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02006.x

56. Burch J. Constipation and flatulence management for stoma patients. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2007;12(10):449-52. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2007.12.10.27282

57. Colwell JC, Bain KA, Hansen AS, Droste W, Vendelbo G, James-Reid S. International Consensus Results. J Wound, Ostomy Cont Nurs [Internet]. 2019;46(6):497-504. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000599

58. Williams J. Considerations for managing stoma complications in the community. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2012;17(6):2669. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2012.17.6.266

59. Hampton S. Care of a colostomy. J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2007;21(9):20-4. Available from: www.jcn.co.uk/journals/issue/09-2007/article/care-of-a-colostomy

60. Perrin A. Convex stoma appliances: An audit of stoma care nurses. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2016;25(22):S10-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2016.25.22.S10

61. Prinz A, Colwell JC, Cross HH, Mantel J, Perkins J, Walker CA. Discharge planning for a patient with a new ostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs [Internet]. 2015;42(1):79-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000094

62. Burch J. Looking after stomas and peristomal skin. Nurs Resid Care [Internet]. 2010;12(9):430-36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/nrec.2010.12.9.77749

63. Chandler P. Preventing and treating peristomal skin conditions in stoma patients. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2015;20(8):386-88. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/ bjcn.2015.20.8.386

64. Smith L. High output stomas: ensuring safe discharge from hospital to home. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2013;22(supl 5):S14-9. DOI: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23568319/

65. Burch J. Current nursing practice by hospital-based stoma specialist nurses. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2014;23(supl 5):S31-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2014.23.Sup5.S31

66. Sarabi N, Navipour H, Mohammadi E. Sexual performance and reproductive health of patients with an ostomy: A qualitative content analysis. Sex Disabil [Internet]. 2017;35(2):171-83. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9483-y

67. Cronin E. Dermatological care for stoma patients. Nurs Resid Care [Internet]. 2008;10(8):382-86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/nrec.2008.10.8.30628

68>68. Burch J. Intimacy for patients with a stoma. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2016;25(17):S26 DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2016.25.17.S26

69. Burch J. Stoma complications encountered in the community, A-Z. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2005;10(7):324-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2005.10.7.18329

70. Burch J. Psychological problems and stomas: a rough guide for community nurses. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2005;10(5):224-27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2005.10.5.18051

71. Beitz JM, Colwell JC. Stomal and peristomal complications. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs [Internet]. 2014;41(5):445-54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000052

72>72. Weerakoon P. Sexuality and the patient with a stoma. Sex Disabil [Internet]. 2001;19:121-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010625806500

73>73. Kirkland-Kyhn H, Martin S, Zaratkiewicz S, Whitmore M, Young HM. Ostomy care at home. Am J Nurs [Internet]. 2018;118(4):63-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000532079.49501.ce

74. Gray M, Colwell JC, Doughty D, Goldberg M, Hoeflok J, Manson A et al. Peristomal moisture-associated skin damage in adults with fecal ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs [Internet]. 2013;40(4):389-99. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0b013e3182944340

75. Berti-Hearn L, Elliott B. Colostomy care. Home Healthc Now [Internet]. 2019;37(2):68-78. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/NHH.0000000000000735

76. Slater RC. Optimizing patient adjustment to stoma formation: Siting and self-management. Gastrointest Nurs [Internet]. 2010;8(10):21-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/gasn.2010.8.10.21

77. Stelton S. Stoma and peristomal skin care: A clinical review. Am J Nurs [Internet]. 2019;119(6):38-45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000559781.86311.64

78. Williams J. Flatus, odour and the ostomist: Coping strategies and interventions. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2008;17(supl 1):S10-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.Sup1.28144

79. Toth PE. Ostomy care and rehabilitation in colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs [Internet]. 2006;22(3):174-77. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2006.04.001

80. Junkin J, Beitz JM. Sexuality and the person with a stoma. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs [Internet]. 2005;32(2):121-28. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00152192-200503000-00009

81. Bonill-de-las-Nieves C, Celdrán-Mañas M, Hueso-Montoro C, Morales-Asencio JM, Rivas-Marín C, Fernández-Gallego MC. Living with digestive stomas: Strategies to cope with the new bodily reality. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2014;22(3):394-400. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.3208.2429

82. Albuquerque AFLL. Tecnologia educativa para promoção do autocuidado na saúde sexual e reprodutiva de mulheres estomizadas: estudo de validação [Internet]. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco; 2015. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufpe.br/handle/123456789/15420

83. Sena JF de. Construção e validação de tecnologia educativa para o cuidado de pessoas com estomia intestinal [Internet]. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte; 2017. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufrn.br/bitstream/123456789/24866/1/JullianaFernandesDeSena_DISSERT.pdf

84. Feitosa YS. Construção e validação de cartilha educativa acerca da prevenção das complicações em pacientes com estomias intestinais [Internet]. Universidade de Fortaleza; 2019. Disponível em: https://uol.unifor.br/oul/conteudosite/F10663420200217112426848515/Dissertacao.pdf

85>85. Schwartz MP. Saberes e percepções do paciente com estoma intestinal provisório: subsídios para uma prática dialógica na enfermagem [Internet]. Universidade Federal Fluminense; 2012. Disponível em: https://app.uff.br/riuff/handle/1/1147

86. Alves RIMB. A prática educativa na ostomia de eliminação intestinal: contributo para a gestão de cuidados de saúde [Internet]. Universidade de Trás-Os-Montes e Alto Douro; 2010. Disponível em: https://docplayer.com.br/4199053-Universidade-de-trasos-montes-e-alto-douro.html

87. Padilla LL. Transitioning with an ostomy: The experience of patients with cancer following hospital discharge [Internet]. University of Ottawa; 2013. Disponível em: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/24291/1/Padilla_Liza_2013_thesis.pdf

88. O’Flynn SK. Care of the stoma: Complications and treatments. Br J Community Nurs [Internet]. 2018;23(8):382-87. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2018.23.8.382

89. Silva DF da. O desafio do autocuidado de pacientes oncológicos estomizados: da reflexão à ação [Internet]. Universidade Federal Fluminense; 2013. Disponível em: https://app.uff.br/riuff/bitstream/1/1027/1/DanielaFerreiradaSilva.pdf

90. Martins LM. A reabilitação da pessoa com estomia intestinal por adoecimento crônico. [Internet]. Universidade de São Paulo; 2014. Disponível em: https://teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/22/22132/tde-09022015-192649/publico/LIVIAMODOLOMARTINS.pdf

91. Martins VV. Saúde sexual de mulheres com estomia na perspectiva da teoria de Nola Pender [Internet]. Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro; 2013. Disponível em: http://www.bdtd.uerj.br/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=5200

92. Readding LA. Hospital to home: Smoothing the journey for the new ostomist. Br J Nurs [Internet]. 2005;14(supl 4):S16-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2005.14.Sup4.19738

93. Alencar TMF, Sales JKD, Sales JKD, Rodrigues CLS, Braga ST, Tavares MNM et al. Nursing care of patients with stomy: Analysis in light of Orem’s theory. Rev Enferm Atual In Derme [Internet]. 2022;96(37):e-021195. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31011/reaid-2022-v.96-n.37-art.1274

94. Zhang X, Lin JL, Gao R, Chen N, Huang GF, Wang L et al. Application of the hospital-family holistic care model in caregivers of patients with permanent enterostomy: A randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs [Internet]. 2021;77(4):2033-49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14691

95. Soares-Pinto IE, Queirós S, Alves P, Carvalho T, Santos C, Brito MA. Nursing interventions to promote self-care in a candidate for a bowel elimination ostomy: Scoping review. Aquichan [Internet]. 2022;22(1):e2212. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/aqui.2022.22.1.2

96. Justicia SH, Moreno VAL, Muñoz MDCM, Quintana AH, Amezcua M. Intervenciones para normalizar las actividades de la vida cotidiana en pacientes a los que se ha practicado una reciente ostomía. Index Enferm [Internet]. 2020;29(3):176-82. Disponible en: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962020000200018&lng=es

97. Zewude WC, Derese T, Suga Y, Teklewold B. Quality of life in patients living with stoma. Ethiop J Health Sci [Internet]. 2021;31(5):993-1000. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v31i5.11

98. Selau CM, Limberger LB, Silva MEN, Pereira AD, Oliveira FS, Margutti KMM. Perception of patients with intestinal ostomy in relation to nutritional and lifestyle changes. Texto Contexto Enferm [Internet]. 2019;28:e20180156. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-265x-tce-2018-0156

99. Silva KA, Duarte AX, Cruz AR, Cardoso LO, Santos TCM, Pena GG. Ostomy time and nutrition status were associated on quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. J Coloproctology [Internet]. 2020;40(04):352-61. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcol.2020.07.003

100. Mo J, Thomson CA, Sun V, Wendel CS, Hornbrook MC, Weinstein RS et al. Healthy behaviors are associated with positive outcomes for cancer survivors with ostomies: A cross-sectional study. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. 2021;15:461-69. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00940-5

101. Bonill-de-las-Nieves C, Díaz CC, Celdrán-Mañas M, Morales-Asencio JM, Hernández-Zambrano SM, Hueso-Montoro C. Ostomy patients’ perception of the health care received. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2017;25:e2961. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2059.2961

102. Santo AC, Pinto MH, Pereira AP, Gomes JJ, Aguiar JC, Silva KG. Collecting equipment for ostomies: User perception of a specialized rehabilitation center. Res Soc Dev [Internet]. 2021;10(10):e65101018681. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33448/rsdv10i10.18681

103. Maydick-Youngberg D. A descriptive study to explore the effect of peristomal skin complications on quality of life of adults with a permanent ostomy. Ostomy Wound Manage [Internet]. 2017;63(5):10-23. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28570245

104. Evans SH, Burch J. An overview of stoma care accessory products for protecting peristomal skin. Gastrointest Nurs [Internet]. 2017;15(7):25-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/gasn.2017.15.7.25

105. Meira IFA, Silva FR, Sousa AR, Carvalho ESS, Rosa DOS, Pereira Á. Repercussions of intestinal ostomy on male sexuality: An integrative review. Rev Bras Enferm [Internet]. 2020;73(6):e20190245. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0245

106. Wang QQ, Zhao J, Huo XR, Wu L, Yang LF, Li JY, Wang J. Effects of a home care mobile app on the outcomes of discharged patients with a stoma: A randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs [Internet]. 2018;27(19-20):3592-602. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14515